Fortifications of Frankfurt

This article may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (September 2019) |

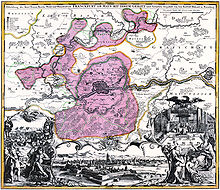

The city fortification of Frankfurt was a system of military defenses of Frankfurt am Main which existed from the Middle Ages into the 19th century. Around the year 1000, the first city wall was formed. It mainly enclosed the area of the Königspfalz Frankfurt. In the 12th century, the settlement expanded to the area of today's Altstadt. For its protection, the Staufenmauer was erected. Starting in 1333, the Neustadt raised north of the Altstadt and was encompassed by an additional wall ring with five city gates. In the 15th century, a Landwehr border was created around the entire territory of the free imperial city. Beginning in 1628, the medieval city wall was improved to a sconce fortress under municipal architect Johann Wilhelm Dilich.

Since its defeat in the Kronberger Fehde of 1389, Frankfurt consistently avoided military conflicts and relied on a net of diplomatic relationships all over the Holy Roman Empire and beyond. For this reason, the city fortification, during the nearly eight centuries of its existence – as far as historic records are concerned – only had to stand a siege once, in the Second Schmalkaldic War, July 1552.

Around the 18th century, the fortification lost its military significance and hindered further expansion of the city. Not least because of this, the walls were torn down from 1806 to 1818. Together with the Wallanlagen, their former position now forms a green belt around the inner city. Seven towers are still preserved, among them the Eschenheimer Turm, a 200 meter piece of the Staufenmauer, remnants of the Landwehr border, and – discovered in 2009 – a 90 meter piece of a casemate that once was a part of the baroque sconce fortress.

First city wall

Königspfalz Frankfurt

Frankfurt's oldest fortifications were created to protect the Carolingian palace ("Karolingische Pfalz") which was first mentioned in documents in 822. For a long time, the location of the palace was unknown to historians. Until into the 1930s, it was thought to have been a predecessor of today's Saalhof. In 1936, Heinrich Bingemer proved by excavations that the Saalhof originated in the Hohenstaufen era, and concluded that the Karolingische Pfalz may have been located more to the east. Indeed, in 1953, archaeological excavations in the core of the historic town, made possible by the bombing and destruction of Frankfurt am Main in World War II, revealed remnants of the historic palace, west of Frankfurt Cathedral, in the basement of the Haus zur Goldenen Waage.[1]

The Pfalz was situated on the Domhügel, a flood-safe elevation in the east of the Altstadt. It originally was an island between the southern Main and the northern Braubach, a river branch that already silted up[2] in the first Christian millennium and was canalized[3] during the Middle Ages. South of the Domhügel was the Ford (German: "Furt"), which gave Frankfurt not only its name but also its existence. West of the Domhügel, between the Domhügel and the Karmeliterhügel, a swampy lowland ran across today's Römerberg to the Main.

Up into the early 20th century, it was considered to be beyond question that the Carolingian Frankfurt not only encompassed the Domhügel, but also the Karmeliterhügel and the south-western part of today's city district Altstadt.[4] This assumption was based on the previously-mentioned assumption that the Pfalz was a predecessor building of the Saalhof, and thus would have been situated in the center of the first fortification. Accordingly, a map by geographer Christian Friedrich Ulrich from the first decade of the 19th century shows the alleged oldest city boundaries and the presumed position of the oldest city walls.

According to this map, the wall allegedly ran from the waterside slightly above today's Alte Brücke to the north, along the Wollgraben, to the later Dominikanerkloster. From there, it allegedly followed the course of today's Braubachstraße and Bethmannstraße, and just before the western end of today's Weißfrauenstraße, made a turn back to the Main in the south, where it connected back to the eastern starting point along the riverside.

Archaeological findings

History of excavations

When, apparently, parts of the wall were brought to light during the construction of the Dompfarrhaus at the northern Domplatz in 1827, and later in the cellars of multiple houses in the western Altstadt area, Ulrich's description of the early medieval fortification was still considered to be confirmed.[4] During the construction of the Braubachstraße through the Altstadt from 1904 to 1906, an opportunity to conduct extensive scientifical excavations was used: Christian Ludwig Thomas, an architect commissioned by the Historical Museum of Frankfurt, was able to confirm the northern and north-western position of the wall in over 50 excavation shafts.[5]

Only after World War II, in the years 1953 to 1955, archaeologists continued the research and inspected the city wall in the area of the Hauptzollamt (today's Haus am Dom).[6] Archaeological studies by Otto Stamm on the area of the Saalhof from 1958 to 1961 proved the position of southern wall parts along the Main and a short western part of the wall below the Saalgasse.[7] The last excavations that were directly made to locate the historic wall were made in 1976, again on the premises of the Dompfarrhaus.[6] Archaeological research to prove the south-eastern and eastern location of the wall has not occurred so far. The stratigraphy in the area of the Römerberg has presumably been significantly damaged by construction works in the Middle Ages and destroyed by the construction of an underground car park in the 1970s, reducing the amount of information obtainable via archaeological means about the wall position in this area.

Archaeological record and current state of research

The most reliably known characteristics of the wall, discovered by archaeology, are the appearance and the composition of the wall.[6][8] On the average, it had a thickness and height of two metres each. For presumedly psychological reasons,[9] it was three metres thick on the Main side in the south. The archaeological finding catalogues thus also often refer to the wall as "Dreimetermauer" (three metre wall). The fortification was made up of coarse gravel and rough-hewn quarry stone, but also partly contained higher-quality pieces made of sandstone from Vilbel and basalt, possibly taken from deconstructed Ancient Roman constructions. The material was pretty crude, and only on the visible sides ["Schauseiten", I assume this refers to the outside of the wall that is seen by possible attackers, translator's note] it had a orderly opus spicatum structure. The mortar was of very low quality, basically consisting of loam mixed with plant fibres and animal hair. According to Thomas, the foundation was so deficient that the wall had a lopsidedness of 30 centimetres away from its vertical direction, back when the wall was not covered by the rubble of later civilizations. Thomas also uncovered wall parts that had apparently been repaired using mortar of higher quality, documenting the importance of the wall: Despite its significant flaws, it was apparently considered to be important enough for restoration.

In regards to age determination, the findings alone do not provide clear information. Thomas attributed the creation of the wall to the 9th century and considered Louis the German to have been the ordering party of the construction. He did so because Pingsdorf ware had been found in the surroundings of the wall, and because Pingsdorf ware was thought to have been Carolingian.[10] During the excavations in 1976, a de:Becherkachel made of coarse mica was salvaged.[6] This type of pottery was invented during the end of the 10th century, and Pingsdorf ware is currently considered to be a post-900 invention too, leading to the conclusion that the wall may not have been a Carolingian construction, but an Ottonian one instead. Additionally, an official document from 994 describes the city as "castello" (castle/fortress)[11], making it reasonable to assume that the wall has existed in 994, matching the archaeological findings.[12]

The position of the historic wall is best documented in the north-west, due to numerous excavations during the turn of the millennium, and due to the then-luxurious archaeological situation of having been able to dig in completely undamaged occupation layers. The fortification was a nearly-ideal (bee-, translator's note)line between the Hainer Hof north of the Kannengießergasse and a 1,10 metre-wide gate discovered by Thomas in the area of the Borngasse. From there, it continued to run to the Steinernes Haus and -- contrary to expectations -- made a sharp turn towards the Römerberg.

The discovery of an east-west wall at the northern Samstagsberg makes it reasonable to assume the existence of another gate, at the position where one leaves the Römerberg today, entering the Alter Markt in the direction of the cathedral.[13] If one draws a line from there to the findings in the area of the Saalhof, it leads to the conclusion that the east-west wall must have made a near-90°-turn at this point, connecting to the stronger wall at the riverbank of the Main directly (in a bee-line, translator's note). However, the significant disruption of the soil below the Römerberg, which was noticed by Thomas, makes it equally possible that the previously-mentioned east-west wall part has been constructed in a later epoch, and that the east-west wall was a direct (Translator's note: word "corner arc", "in einem Viertelkreis", removed intentionally during translation: confusing, unclear, conflicts with "direct" in a geometrical sense, as an arc is never a direct connection between two points. It may be reasonable to remove "direct" and replace it by "corner arc" in some way instead. See the German original version) connection between the north-west wall and the southern part of the wall. It was Otto Stamm who found the most-south-western part of the north-west wall under the Saalgasse.[6] The southern part of the wall has, archaeologically, only been confirmed to have existed up to the height of the Geistpförtchen. Furthermore, the simultaneous existence of the southern wall and the Ottonian wall is disputed.[14]

Presumedly, the "Dreimetermauer" (three-metre wall, referring to the thickness of the wall at the Main, translator's note) followed the natural course of the river east of the Geistpförtchen as well. The riverside, back then, was at the same height as the southern Saalgasse. The wall then presumedly ran east of the cathedral, about in the middle of the Kannengießergasse, from north to south, connecting back to the proven position of the wall along today's Braubachstraße. (This was a nightmare to translate and may contain errors, translator's note)

The surprising archaeological findings of the 20th century have been explained by excavations of the post-war era. Exactly in the middle of the wall-enclosed area, the Carolingan Pfalz was located together with its associated farm buildings and the predecessor of the cathedral, the 852-consecrated Salvatorkirche. The Carolingian Frankfurt thus has been much smaller than historically expected, and its fortification, according to present knowledge, has been built by the subsequent Ottonian dynasty around 1000 Anno Domini.

The Staufenmauer

In the beginning of the 11th century, the Carolingian royal palace ("Königspfalz") had already become ruinous. Presumedly between 1018 and 1045, it was destroyed by a fire, and the ruins were quickly overbuilt.[15] Only Conrad III of Germany, elected king in 1138, ordered the construction of a new king castle ("Königsburg"), the Saalhof, at the Main river, again. The settlement around the castle developed into a little city over time. In course of the later so-called First City Expansion (Erste Stadterweiterung), the boundaries of the city expanded beyond the naturally or artificially silted-up northern Main river branch. At the end of the 12th or the beginning of the 13th century, the enlarged city was surrounded by a new wall, the Staufenmauer. [16] It enclosed an area of about 0.5 square kilometers, today's Frankfurter Altstadt.

The new city wall was located at the Main river shore, slightly above the bridge (likely Alte Brücke, translator's note), running to the north along the Wollgraben up to the later Dominikanerkloster, and from there in a large arc north-west towards the Bornheimer Pforte at the Fahrgasse. From there, it ran in a western direction along today's Holzgraben towards the Katharinenpforte, then in an arc along the Kleiner and Großer Hirschgraben towards the south-west, and made a sharp turn just before the western end of today's Weißfrauenstraße, towards the Main in the south. Along the Main, there was the Mainmauer ("Main (river, translator's note) wall").[17]

The expansion occurred approximately at the time of the invention of the crossbow following the Crusades, causing the most significant part of the expansion to be vertical, increasing the height of the wall. At the top of the about seven metre high and two-three metre thick wall, a Chemin de ronde was situated. On the outer side of the wall, there was a dry moat. The city wall had three main gates: From the west to the east, the Guldenpforte at the western end of the Weißadlergasse; the Bockenheimer Pforte (later called "Katharinenpforte") between the Holzgraben and the Hirschgraben; and the Bornheimer Pforte at the northernmost point of the Fahrgasse.[18]

The appearance of the Guldenpforte is only documented by the siege plan of 1552, as a round, undecorated tower with a conical roof. The Katharinenpforte consisted of two simple buildings, the outer gate and a stronger, cuboid inner tower with a high slate roof, a roof bay window and a roof lantern. This tower was situated at the south end of today's street "Katharinenpforte", which was named after St. Catherine's Church of Frankfurt, a church founded by Wicker Frosch in 1354. On older depictions, the Romanesque architecture of the gate can be recognized by the size and shape of the windows, as well as by the round arch thoroughfare with its typical unplastered arches at ground level.[19]

Already in the 17th and 18th centuries, the Katharinenpforte was expensively renovated multiple times to maintain the usability of a prison located within it. Apparently, the building with its noticeably massive walls was especially well-suited for this usage. The most notable prisoner by today's standards may have been Susanna Margaretha Brandt :de:Susanna Margaretha Brandt, the historical prototype of Goethe's Gretchen de:Gretchentragödie. In the tower, she spent the time between her apprehension on 1771-08-02 and her execution on 1772-01-14.

The Bornheim gate ("Bornheimer Pforte") was a double gate: The eastern gate was larger and made for horses and carts, the western gate was about half as wide and made for pedestrians. The Bornheim gate had a cuboid tower with a high slate roof. It already served as a prison in 1433, like its western counterpart. In 1719, it was severely damaged during the Großer Christenbrand (intentional redlink, see :de:Großer Christenbrand, translator's note).[20]

Aside from the previously mentioned main gates, there have been seven smaller passages: the Mainzer Pforte at the Alte Mainzer Gasse, the Fischerfeldpforte east of the Main bridge, west of the bridge the Fischerpforte at the Große Fischergasse, the Metzgertor south of the Leinwandhaus, the Heilig-Geist-Pforte at middle length of the Saalgasse, the Fahrpforte at the later Fahrtor, the Holzpforte at the southern end of the Karpfengasse (north-south connection approximately between today's streets Fahrtor and Am Leonhardstor, abandoned after WW2) as well as the Leonhardspforte at the 1219-founded Church of St. Leonhard.[21]

The smaller passages, due to their low size, have been belittled in colloquial speech, as "Pförtchen" (diminutive form of "gate". Would "gatelets" be a good translation?). Their exact original appearance is unrecorded, as they have been considerably modified during constructions in the 15th century, almost a century before the first pictures of the whole city have been drawn.

The Staufenmauer was still being maintained after the second city expansion ("Zweite Stadterweiterung") of 1333 as well. The most suitable proof of this have been two round towers, constructed on top of the wall in the middle of the 14th century, at a time when the city was already receiving a new fortification. The Fronhofturm ("Fronhof tower"), named after a vicinal farmyard of the Bartholomäusstift, was located at the end of the Predigergasse (east-west connection approximately between today's eastern Domplatz and the Kurt-Schumacher-Straße, abandoned after WW2). The Mönchsturm ("monk tower"), named after the neighbouring Dominicans,[22] was located about at the middle of an imaginary bee-line between the Choir of the Dominican church and the Steinernes Haus in the Judengasse ghetto. The towers have likely been intended to be a protection of the endangered wall corner at the Fischerfeld.[23]

Only (not before; the German original word "erst" doesn't say anything about the future, translator's note) at the end of the 16th century, larger parts of the wall were deconstructed, as visible on the Bird's-eye view by Matthäus Merian of 1628: 1583, a large piece of the wall south-west of the Katharinenpforte was demolished; 1589, a breakthrough was made at the northern end of the Fahrgasse; and in 1590, a similar breakthrough was made while connecting the Hasengasse to the Zeil.[24] In the same year, the Guldenpforte was deconstructed too; this also happened to the Bornheimer Pforte shortly after 1765. In 1790, the Katharinenpforte was deconstructed; in 1793, the Fronhofturm (Fronhof tower) was deconstructed; and in 1795, large parts of the Mönchturm (monk tower) have been deconstructed. The latter, previously used for gunpowder storage, had almost caused a huge disaster that was only barely prevented by not letting the fire spread to it; as a consequence, it had been unused ever afterwards. The clock of the Bornheimer Pforte that had originally been requested by the neighbours in 1603, was moved to the tower of the armory at the Konstablerwache in 1778. The armory was later deconstructed in 1886. In 1776, the bell (yes, that was a wikilink to "bell", not a specific bell article, translator's note) was moved to the Johanniskirche in Bornheim as a makeshift in the year that the church burned down.(interpretation: "as a makeshift *after* the church had burned down earlier that year." The original text does not explicitly say this; it could theoretically also mean that the church burned down after the makeshift replacement. Translator's note.) [25]

After the defortification of the early 19th century, an about 600 metre-long part of the Staufenmauer still existed from the western backside of the Judengasse up to the Fahrgasse, uninterrupted until 1880. Within a few years, more than 500 metres of this part have been deconstructed during the breakthrough of the Battonnstraße (Battonn street), and during the construction of a school building at the Dominikanerkloster.[24] The fundaments of the Mönchturm (monk tower) have been discovered archaeologically in 2011 and are now planned to be visualized at the top of the road.[22]

The late medieval city expansion

On 17 July 1333, emperor Ludwig IV. authorized the second city expansion (Zweite Stadterweiterung) which tripled the previous city area.[26] It took four centuries for the city population of 9000 people to grow enough to cover the whole Neustadt in front of the Staufenmauer with buildings. Notwithstanding, shortly after the city expansion, the construction of a new city wall around the sparsely inhabited suburbs was started and took over 100 years in multiple construction phases.

The construction works began in 1343, from two sides: in the west at the Weißfrauenkloster and the Bockenheimer Tor; in the east at the Allerheiligentor (All Hallows' Gate). The construction was slow in the beginning, and as far as comprehensible from the medieval architect and arithmetician logbooks, did not have an overall concept to follow. Only for the strengthening of the front Main wall during the 40s and 50s of the 15th century, a kind of plan/concept seems to have existed. The introduction and quick development of firearms seems to have caused an acceleration of the construction work, causing the whole fortification to be finished by the beginning of the 16th century.

Similar to its predecessor, the new fortification started above the Alte Brücke, ran up to the Dominikanerkloster in the north, then to the east, and from there, followed the line of today's Anlagenring. From east to west, this includes the Lange Straße, the Seilerstraße, the Bleichstraße, the Hochstraße and finally the Neue Mainzer Straße down to the Schneidwall. The course of the Main wall did not change. For the first time in history, the Sachsenhausen suburbs south of the Main became encompassed by the protection of the wall.[27]

The wall was six to eight metres high, and at the top of the wall, it had a thickness of about 2.5 to 3 metres. To reduce the usage of construction materials, the inner side of the wall -- just like the Staufenmauer -- was constructed with one-metre deep blind arches. At the top of the wall, there was a continuous chemin de ronde with a parapet that had a height of about two metres and was interrupted by merlons and embrasures. It was accessible via narrow, steep wooden stairs, or via stone spiral stairs, so-called "snails" ("Schnecken").

The chemin de ronde, paved with [likely stone, translator's note] slabs, was partially sheltered by a slate gable roof. On the unsheltered rest of the wall, at multiple points, little houses allowed defenders and guards to sojourn. The most notable of these houses was the Salmensteinisches Haus, built around 1350 in the area of today's Rechneigrabenstraße. In the 19th century, it inspired the architects of the townhall reconstruction, causing the small townhall tower Kleiner Cohn to become an exact copy of the historical house. Due to damages from WW2, the roof, however, has been replaced by a flat makeshift roof and remained like this ever since.

Each in front and behind of the wall, there had been 3-4 metres wide Zwingers; in front of the outer Zwinger, there was an 8-10 metre wide wet moat with another, smaller, wall in front of it. In addition to the Main, multiple smaller rivers filled the moat with water. The Fischerzunft of Frankfurt also cultivated fisheries in the moat. The Rechneigrabenweiher in the Obermainanlage and the Bethmannweiher in the Bethmannpark still exist today and have historically been part of the moat.[28]

As enhancements of the wall, there have been 55 towers, 40 of which have been located on the northern Main side, and 15 of which have been located in Sachsenhausen. Most of them have only(relatively late, translator's note) been constructed during the 15th century. Most of the towers have been round and did not stick out much on the outside of the wall. The chemin de ronde either passed through the towers or around them.[29]

Gates

The Landmauer contained only a few gates: in the west, the Galgentor; in the north-west, the Bockenheimer Tor; in the north, the Eschenheimer Tor; in the north-east, the Friedberger Tor; and in the east, the Allerheiligentor. On the Sachsenhausen side, there was only one single gate, the southern Affentor (ape gate; this name is explained at the end of this section); the eastern Mühlpforte and the south-western Oppenheimer Pforte had been deconstructed before 1552, as visible on the besiegement plan.

The gates consisted of two slightly stronger gate towers on both sides of the moat and a Zwinger in between. To improve the defendability of the gates, most of the gates have been offset against each other; only the Bockenheimer Tor and the Eschenheimer Tor had straight-line throughfares. Via an opening in the gate vaults, it was possible to pour dirt and stones into the passage, making it impossible to pass.

The Galgentor (gallows' gate), despite its deterrent name, was the most important gate; the traffic from and to Mainz passed through it. The emperors also preferred to enter the city via the Galgentor after[/during/in course of? (German original: "bei")] their election. The gate's cuboid tower, constructed from 1381 to 1392, thus had an especially representative design: On the outer side, below gothic baldachins, statues of Bartholomew the Apostle and Charlemagne stood between a Reichsadler which stood on a lion. In 1808, the whole construction, together with its tower and the bridge in front of it, was demolished.[30]

As one of the first finished fortification parts of the new city wall, the tower of the Bockenheimer Tor was built from 1343 to 1346. First named "Rödelheimer Pforte", it later inherited the name of the Katharinenpforte in the 15th century. After the gate was severely damaged by lightning strikes in 1480 and 1494, it was reconstructed in 1496 and decorated by painter Hans Fyoll. In 1529, it was protected by a roundel in front of it; in 1605, the old gate was closed and a new one was built next to it. The deconstruction happened in 1808, after the then-town-master-mason had already pointed out the tower's considerable decrepitude in 1763.[31]

The most important tower was the Eschenheimer Turm, constructed from 1400 to 1428 and still existent behind the eponymous city gate. It already was the second tower at this position. The foundation stone of its predecessor was laid in 1346. The outwork of the tower was deconstructed in 1806. On the contrary, the tower itself survived multiple deconstruction ambitions: Although it was considered by some people to be a traffic obstruction, and considered by some people of the Biedermeier epoch to be an unaesthetic insult to the Biedermeier aesthetics, it always found prominent defenders in the population, such as the Grand Duchy of Frankfurt, Karl Theodor von Dalberg, to whose honor the tower was called Karlstor during the 19th century.[32]

According to historical messages, the Friedberger Tor already existed in 1346, but its tower was constructed many years later, in 1380. The tower was cuboid and had a high, hipped roof with a roof lantern on the top. Its front building was deconstructed in course of the fortification improvements of the 17th century. The freestanding tower itself, however, was inhabited by a watchman until 1812, when the tower was deconstructed as well.[33]

The Allerheiligentor (All Hallows' Gate) was originally named Rieder Pforte after the Riederhöfe, which have been located within a walking distance of about half an hour. In historical documents, the name Hanauer Tor also appears for the gate. Only when, in 1366, the Allerheiligenkapelle was constructed near the gate, its name slowly passed over to the gate as well. The exact construction date of the representative gate tower varies between multiple historical sources, between the 1340s and the 1380s. Its deconstruction happened in 1809.[34]

The Sachsenhäuser Tor (Sachsenhausen gate) had already been called Affentor (ape gate) since the end of the 14th century. There are multiple possible explanations for this name. According to Johann Georg Battonn, the name was influenced by a corner house named "Eckhaus zum Affen" near the gate.[35] In its whole appearance, it was noticeably more compact than the gates north of the Main. At the top of the gate, there was a cuboid tower, the exact construction date of which can not be reconstructed anymore. After 1552, the gate gained roundels on two sides; after 1769, the roof of the gate gained a small baroque tower to accommodate the chiming clock of the broken Sachsenhäuser Brückenturm. The gate was completely deconstructed in 1809.[36]

Main river bank and bridge towers

Especially important for the protection of the city was the defense of the Main river bank. At the downstream side, two massive fortification buildings, the Mainzer Turm ("tower of Mainz") at the north river bank and the Ulrichstein at the south riverbank, guarded the entrance to the city. Upstream, the swampy fishing fields prevented direct access to the city wall, while the Sachsenhausen riverbank between the city wall and the Main bridge was protected by a wall with five massive towers.

The bridge itself was protected by two bridge towers. Their gates were closed at night, to prevent anyone from passing the bridge by night. In 1306 already, historical documents mentioned the towers that had been destroyed by flood and ice flow on 1 February of the same year. Apparently, however, they have been reconstructed within a very short timespan. In July 1342, the less massive Sachsenhäuser Brückenturm (Sachsenhausen bridge tower) fell victim to flooding again but was immediately reconstructed from 1345 to 1380.

The Frankfurter Brückenturm (bridge tower of Frankfurt) was also called "alter Brückenturm" (old bridge tower) in historical documents since 1342, making it possible to assume that it was constructed between 1306 and 1342. It served as a prison, and the torture of the Katharinenpforte was moved to this tower in 1963. The cuboid tower had a very steep hipped slate roof with large dormers and an ogival thoroughfare at ground level. While the edges of the tower exposed ashlars, the sides of the tower were plastered and shaped decoratively all the time. The form of the decoration varied over the centuries due to varying contemporary taste.[37]

The Sachsenhausen Brückenturm, too, had a quadrangular horizontal section (that means "it was cuboid". Perhaps we should just write that. It, too, "was cuboid". That's it. Translator's note.) and had an ogival thoroughfare at ground level. However, its upper part was reminiscent of gothic patrician houses of the time. It had a chemin de ronde with polygonal small corner towers, and the chemin de ronde protuded in form of a round lombard band. The upper end of the tower consisted of four tented roofs and a hipped slate roof. Painted decoration, as far as replicable, did not exist on it at any time. The tower was deconstructed in 1769.[38] In a tribute to its style, at the beginning of the 20th century, a new large tower, the Langer Franz, became a part of the new town hall.

On the northern side of the Main, already since the Staufer epoch (Stauferzeit), a wall ran en bloc between the Alte Brücke and the Mainzer Turm (tower of Mainz) and was only passable through six gates. The closest gate to the bridge was the Fischerpforte, last rebuilt in 1449. Its tower was already deconstructed before the besiegement of 1552, so its appearance (which thus does not appear on the siege plan of 1552, I guess, translator's note) is unknown. The remaining tower stub had gable-like battlements above the thoroughfare. Between the gate and the bridge tower, there was a brick-built triangular bulwark with many murder holes and an oriel window. The construction of this additional fortification apparently happened in 1520; the exact deconstruction date is not reconstructible.[39]

The Metzgertor (butcher's gate), to the west, last renovated from 1456 to 1457, was located at the exit of the butchers' village (Metzgerviertel) next to the slaughterhouse. It's cuboid tower had unplastered edges with exposed ashlars, an ogival throughfare and three upper floors with two small rectangular windows each. The steep hipped roof had a large oriel window towards the Main. Gate and tower have been deconstructed in October 1829, to make place for a free harbour, and to allow the Leinwandhaus :de:Leinwandhaus (Frankfurt am Main) behind it to become a storehouse.[40]

South of the Heilig-Geist-Spital (holy spirit hospital) at the Saalgasse, there was the Heilig-Geist-Pforte (holy spirit gate), constructed in 1454. Its cuboid gate tower was slightly lower than the nearby Metzgertor's tower, and it had only two upper floors with rectangular windows above the ogival thoroughfare. At the front of its gabled roof, however, there was a large oriel window as well. The tower was sold to merchant Siebert for demolition when Siebert rebuilt the northern adjacent houses of the Saalgasse and overbuilt the gate in the process.[40]

The main entrance at the Main river bank was marked by the Rententurm, the construction of which finished in 1456, and the Fahrtor of master municipal worker and stonemason Eberhard Friedberger :de:Eberhard Friedberger, the construction of which finished in 1460. While the Rententurm still completely exists as a part of today's historical museum, the Fahrtor was deconstructed in 1840.[41] Only its sculpture-decorated oriel window is still visible at the western outside of the museum; a replication exists at the south side of the new town hall.

The Holzpforte gained its final appearance in 1456. Its ogival thoroughfare had only low height and was apparently made only for pedestrians. The tower above it also only had one upper floor, but a very steep gabled roof with a polygonal oriel window and a spire at the top. Directly above the gate, there was another gothic oriel window with tracery decoration and the year number "1456" in the wall. As a specialty, it was open at the bottom, for communication and defense purposes. The little gate was deconstructed in 1840.[42]

As the most western entrance from the Mainkai to the city, the Leonhardstor existed, reconstructed in 1456 as well. It was, like the Holzpforte, a simple building with only one upper floor. This may have been caused by the vicinity of the large, massive Leonhardsturm that had already been constructed from 1388 to 1391 and that contained important documents of the city until into the 17th century. With its four upper floors, a round lombard band protruding from the top floor, and a conical roof with four oriel windows, the Leonhardsturm was faintly reminiscent of the Eschenheimer Turm. The tower, once constructed much to the displeasure of the Leonhardsstift, was deconstructed in 1808; its gate was demolished in 1835.[43]

The Mainzer Pforte closed the Main front and, at the same time, opened the west front of the Landmauer. The narrowness of the bridge above the moat at this position, even on the earliest depictions, leads to the conclusion that it has always only served pedestrians. The original Romanesque gate building from the time of the first city expansion has been reconstructed from 1466 to 1467. The southern adjacent Mainzer Turm, first mentioned in documents of 1357, was located at the top of one corner of the main wall and the western city wall. It was a massive, round tower with a round lombard band protruding from the top floor, and with an open chemin de ronde. The uppermost floor, octagonal in shape, had a bell-shaped roof with a roof lantern. In 1519 and 1520, the Mainzer Bollwerk (bulwark of Mainz) was reinforced once more, using roundels, likely due to a feud threat by Franz von Sickingen. In colloquial language, this mightiest bulwark of the city fortification was called "Schneidwall", due to sawmills (Schneidmühlen) which were powered by water from the Main via a millrace.[44]

The Schaumaintor (look-(at)-Main-gate) at the Sachsenhausen river bank (Sachsenhäuser Ufer) got its name after it had been enlarged to be able to cope with the additional traffic of the defunct Oppenheimer Pforte. Before that, it had also been called "Mainzer Pforte" (gate of Mainz). To its protection, a strong round tower, the Ulrichstein, existed. It had first been mentioned in documents of 1391 and had a conical spire with oriel windows. During the decampment of the Swedes in 1635, it was severely damaged.[45] Its ruin still remained in place after the deconstruction of the Schaumaintor in 1812 and was removed only in 1930, to make way for street traffic.

Military importance

Shortly after the completion of its construction in the 16th century, the city wall was already militarily and technically obsolete. It had been designed as medieval protection against cutting and stabbing weapons, bows, and crossbows. Since the 14th century, however, firearms, especially cannons, revolutionized the besiegement techniques. At the latest, the fall of Constantinople in 1453, during which the strongest city fortification in the world was overcome by large cannons, marked a turn of eras.

The fortification of Frankfurt endured its most significant performance test in July 1552.[46] During the Second Schmalkaldic War (Fürstenaufstand), protestant troops under command of Maurice, Elector of Saxony, besieged the protestant but emperor-loyal city for three weeks. The city was protected, successfully, by troops of the catholic emperor under the command of Conrad von Hanstein :de:Conrad von Hanstein. To achieve this victory, Hanstein ordered rapid improvements of the fortification, the creation of makeshift bastions, and the demolition of the gotical spires on the Bockenheimer and Friedberger gate that had been blocking the line of fire of the defense's own artillery.

The Peace of Passau ended the besiegement. It had been the largest military and diplomatic achievement of Frankfurt's history. The city had successfully defended its Lutheran confession as well as its privileges as a trade fair location and as an election and coronation place for the Holy Roman Emperors. Starting in 1562, almost all of the emperors have not only been elected, as usual before but also been coronated solemnly, in Frankfurt.

The Landwehr

Mid 14th century, at the time of the second city expansion (Zweite Stadterweiterung), Frankfurt already had a sizeable rural district. Part of this district, on the right side of the Main, clockwise, have been the Riederfeld, the Friedberger Feld and the Galgenfeld, which approximately encompassed the area of today's Ostend, Nordend, Westend, Gallus, Gutleutviertel and Bahnhofsviertel. On the left side of the Main, the rural district encompassed the Sachsenhausen village with its Feldmark along the Main, and the Sachsenhausen mountain ("hill" may be more accurate than "mountain", translator's note) (Sachsenhäuser Berg). In 1372, the city bought the Reichsschultheißenamt from emperor Charles IV for 8,800 guilder, making the city a Free imperial city, and it bought the Frankfurt City Forest, a 4800 hectare area of the imperial forest Dreieich (Reichsforst Dreieich) for another 8,800 guilder. Additionally, Frankfurt owned the village Dortelweil at the Nidda, and had rights to the imperial villages (Reichsdörfer) Sulzbach und Soden. In 1367, the city bought the castle and village Bonames, in 1376 it bought Niedererlenbach, and in 1400 it bought the castle Wasserburg Goldstein :de:Wasserburg Goldstein.

The battle of Eschborn

Despite the Peace of Passau proclaimed by Charles IV, the properties of Frankfurt have persistently been at risk, especially due to the interests of Kronberg's knights (Kronberger Ritter) and the leaders of Herrschaft Hanau :de:Herrschaft Hanau (Hanau) who wanted to keep the ambitious imperial city Frankfurt (Reichsstadt Frankfurt) in its place. In 1380, the knights united in the Löwenbund de:Löwenbund; the cities formed a counter-union in the Rhenish League of Towns. Frankfurt's attempt to secure its position by military force, however, was not successful. In the Battle of Eschborn on 14 May 1389, the city was resoundingly defeated by Kronberg and its allies from Herrschaft Hanau, Burg Hattstein :de:Burg Hattstein and Burg Reifenberg :de:Burg Reifenberg (Oberreifenberg). 620 citizens, among them some patricians and all bakers, butchers, locksmiths and shoemakers, were taken prisoners. To free them, and to convert the war enemies to allies, Frankfurt was forced to pay ransom money as a last resort. With a large effort, it managed to offer 73,000 guilder as ransom money until 1 March 1393, appointed knight Hartmut von Cronberg as the bailiff of all villages that belonged to the city, with Bonames as his location of office, and with an annual salary of 184 guilder.

Construction of a Landwehr around the city

In the beginning of 1393, plans for the construction of a Landwehr, a type of border, emerged for the first time. In 1396 and 1397, the Landwehr was constructed from the Riederhöfe in the east to the Knoblauchshof in the north of the city. On each of the two farmyards, additionally, a wooden observation tower was built by the city. The constructions displeased the neighbors in Bad Vilbel and Hanau, so the city council protected its decision by obtaining a privilege from Roman-German king Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia on 13 January 1398. The privilege allowed the city to construct moats, Landwehrs and observation towers in and around Frankfurt and Sachsenhausen at their own discretion. Already in the same year, the city council resumed the construction of the Landwehr and finished the construction of the north-western arc between the Knoblauchshof and the Gutleuthof at the Main.

The new Landwehrencompassed the city at a distance of about three to four kilometres. Its position was approximately equal to the political boundaries of the free imperial city. It consisted of an impenetrable hedge and a moat in front of it. The western part of the Landwehr was later gradually complemented by a second moat.

The area between the city wall and the Landwehr consisted mainly of agricultural land. Directly in front of the city, there have been gardens and vineyards. The outlying suburbs, approximately located along today's Alleenring, have been used agriculturally in accordance with traditional Flurzwang rules similar to a medieval three-field crop rotation system (Dreifelderwirtschaft). Additionally, a circle of fortified farmyards surrounded the city. One part of the area was cultivated with summer grain, an other part with winter crops, and a third part lay idle. Between these parts, there have been multiple smaller woods and meadows like the Knoblauchsfeld and the Friedberger Feld, the latter of which was important for the water supply of the city. A wooden water supply pipe connected it to the Friedberger Tor since 1607.

Landwehr of Sachsenhausen

In 1413, the construction of the Sachsenhausen Landwehr (Sachsenhäuser Landwehr) began in the south of the suburb. In 1414, the Galgenwarte and the Sachsenhäuser Warte have been created as the first stone parts of the Landwehr. These measures attracted the attention and displeasure of another mighty enemy of the free imperial city: Werner von Falkenstein (:de:Werner von Falkenstein, :fr:Werner de Falkenstein), archbishop of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Trier, lord of Königstein and count of Castle Hayn (:de:Burg Hayn), felt that his feudal law rights to the hunting area Wildbann Dreieich (:de:Wildbann Dreieich) were impaired by the construction of the Landwehr and the observation towers. The city council, however, referred to the privilege obtained from king Wenceslaus IV of Bohemia, and asked him for help. Later, they also asked Sigismund, German king and future Holy Roman Emperor, for assistance. Sigismund personally examined the Galgenwarte (gallows' observation tower) and confirmed Frankfurt's privileges. Notwithstanding, the archbishop gave the order to destroy the Sachsenhäuser Warte (observation tower of Sachsenhausen) and the Sachsenhäuser Landwehr (Landwehr of Sachsenhausen) in 1416. King Sigismund, who was in London at time of the destruction, urged the archbishop to behave peacefully, and asked the city council to wait for his return to Germany to make a decision. Only after Werner's death in 1418, the city council ordered the reconstruction and completion of the Landwehr from 1420 to 1429. From 1434 to 1435, the Bockenheimer Warte (observation tower of Bockenheim) was constructed. In 1470 and 1471, a new Sachsenhäuser Warte (observation tower of Sachsenhausen) was constructed.

Expansion of the Landwehr in the 15th century

In 1425, the city purchased Oberrad, a village located east of Sachsenhausen. It became a part of the Landwehr-protected area in 1441. In 1474, following long efforts, the city council managed to detach Bornheim from Amt Bornheimerberg (:de:Amt Bornheimerberg) and to purchase it as well. To be able to include Bornheim within the Landwehr, significant diplomatic preparations were required. As the city council feared resistance especially from Philipp I, Count of Hanau-Münzenberg, they asked for confirmation of their Landwehr privilege without explicitly mentioning Bornheim in their request.

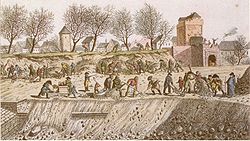

On 23 and 24 July 1476, about 1500 citizens of Frankfurt and its villages went to the field in front of Bornheim and trenched the moat of the new part of the Landwehr together. The position of the moat had been marked before. All 42 members of the city council were present during the construction works, and they had ordered armed servants and cannons to be placed on the Knoblauchshof and the Günthersburg to protect the workers. With the construction of the new Bornheimer Landwehr, the Landwehr part between Frankfurt and Bornheim became redundant.

In 1478, the Bornheimer Landwehr was completed with the construction of the Friedberger Warte (observation tower of Friedberg). The previous observation tower at the Knoblauchshof, between the Eschersheimer Landstraße and the Eckenheimer Landstraße, was abandoned as the traffic flow changed. The traffic to Bad Vilbel now passed the Friedberger Warte; the traffic to Ginnheim und Eschersheim passed the Bockenheimer Warte.

Only the five largest arterial roads allowed passage through the Landwehr. These passages were protected by observation towers: The Galluswarte at the Mainzer Landstraße; the Bockenheimer Warte at the Bockenheimer Landstraße; the Friedberger Warte at the Friedberger Landstraße; and the Sachsenhäuser Warte at the Darmstädter Landstraße.

To protect the fifth passage, at the Hanauer Landstraße, there have been the two Riederhöfe. Those who wanted to pass this border had to pass three boom barriers. In defiance of a contract from 1481, boundary disputes with the people of Hanau persistently occurred, and the Reichskammergericht had to deal with these disputes all the time until it was dissolved. On 26 March 1605, 300 soldiers of Hanau ravaged the outer Riederschlag and pestered Frankfurt's guards who barely managed to signal distress using horns and guns. Of the year 1675, Frankfurt is reported to have unearthed a boundary post of Hanau, removed Hanau's coat of arms from it, cut the post into pieces and battered the coat of arms into pieces. Only in 1785, the position of the border was finally agreed upon in a contract.

The Eschenheimer Landstraße(highway of Eschenheim) had not been passable without interruption anymore since 1462. The boom gate at the Landwehr was usually closed; only the millers of Niederursel and the village mayors of Frankfurt's villages had a key to open it themselves. Plans to construct a new observation tower had never been implemented. Only in 1779, after many requests, the people of Eschersheim received a key for the boom gate as well.

In the 16th century, the military usefulness of the Landwehr was put to the test multiple times. In 1517, during the autumn fair of Frankfurt, Franz von Sickingen ambushed a convoy of merchant vehicles within the Landwehr, in front of the Galgentor, and stole seven trading vehicles from Frankfurt. From 28 to 30 August 1546, in the Schmalkaldic War, the troops of the Schmalkaldic League, defenders of the city, successfully forced the emperor's troops to retreat from their attacks on the Landwehr at the Galgenwarte, the Bockenheimer Warte and the Friedberger Warte.

During the besiegement of Frankfurt in July 1552, however, the Landwehr failed to withstand the attacks. The first onslaught of the Elector of Saxony's troops already broke through the Landwehr at the Friedberger Warte, destroyed the Galgenwarte and the Sachsenwarte, plundered a herd of 3000 head of cattle and set up their camp directly in front of the city wall. Today's city names Im Sachsenlager ("in the Saxon camp") and Im Trutz Frankfurt at the west end of the city are remnants of this event.

Although the Landwehr and the destroyed observation towers were reconstructed after the allies' departure, neither of them played an important role during the wars of the 17th and 18th centuries. From 1785 to 1810, these fortifications have gradually been deconstructed.

Baroque city fortification

After the successfully overcome besiegement of 1552, Frankfurt was spared from military threats for over 50 years, during which the city saw no reason to improve its fortification. Experienced military personalities asked for stronger protection, but they did not manage to convince the city council of a need for large defensive measures.

Frankfurt's nearly-unscathed survival of the besiegement, however, was not caused by its fortification, which was already outdated at that time. It was rather caused by the resolute defense by numerous cannons, against which the attackers lacked proper countermeasures. In the second half of the 16th century, weapons powered with gunpowder (so-called "Pulvergeschütze") made their final breakthrough. They rendered medieval stone fortifications obsolete, but they did require the construction of structures that the weapons could be placed on. For this reason, during and shortly after the besiegement of 1552, Frankfurt's city wall was selectively upgraded with bastions and roundels. Additionally, the makeshift bastions of the time before the besiegement were solidified and partly expanded, for example at the so-called Judeneck south of the Allerheiligentor (all hallows' gate).

All of these measures, however, would not have been sufficient to properly defend the whole city wall in case of a new attack. Numerous wars in Italy had already led to a new defense theory at the end of the 15th century. It became apparent that straight-line walls were more useful for defense than semicircular walls. For this reason, after multiple experiments, pentagonal bastions, also called bulwarks, connected by curtain walls ("Kurtinen"), were considered to be the ideal form.

Beginning of the Thirty Years' War

With the eruption of riots in Bohemia in 1618, the Thirty Years' War began. However, only when Matthias, Holy Roman Emperor, died in 1619, the political situation escalated dramatically. This caused the city council of Frankfurt to contact Adam Stapf, an engineer from the Electoral Palatinate who was working as a fortress architect in Mannheim, in the same year.[47] He submitted a plan to the council, with a cost estimate of 149,000 guilder. According to this plan, hollow bastions were to be created: 13 north of the Main, 5 south of the Main. To further save costs, instead of the construction of curtain walls, the plan suggested to bank up earth behind the old Zwingermauer, making it usable as breastwork. The city council immediately declined the offer with reference to the high costs. However, already in 1621, due to the increasing risk of war, the council felt compelled to contact Stapf again.

Stapf, now working in Heidelberg, immediately presented a new plan. According to it, the medieval fortification was to be left untouched, and in a larger distance from the city, a completely new fortification was to be constructed with 13 bastions and 12 curtain walls. The estimated costs were, according to Stapf, 159,600 guilder. In a conference on 10 May 1621, the city council expressed the opinion that the war likely ended soon, and that the construction of a huge new fortification should better not be done.

Soon, it became clear that the war could also reach Frankfurt: In the Battle of Höchst on 20 June 1622, in close proximity to the city, more than 40,000 soldiers of the Protestant Union and the Catholic League faced each other. After the retreat of the protestant troops, the city found itself compelled to be generous towards the catholic victor. To be able to uphold their Lutheran confession while retaining their imperial privileges and avoiding involvement in the war, the people of Frankfurt began a policy of benevolent neutrality towards all sides, without agreeing to join any alliance. While the most important weapon in this strategy game were the well-filled city coffers, to be on the safe side, a demonstration of military strength was considered to be necessary as well.

Already in the same year, Eberhard Burck, engineer and master builder in Giessen, was temporarily commissioned to improve the fortification for two years. Following his recommendation, the city council also commissioned Steffan Krepel of Forchheim as wall master ("Wallmeister". Master wall architect? translator's note) for one year. According to Burck's plan, which was apparently focused on cost reduction, Frankfurt was supposed to receive six bastions, Sachsenhausen only three; as curtain walls, like in Stapf's first plan, the old Zwingermauer was to be reused. In January 1624, Burck requested a salary ("Recompens") for his draft, and Krepel complained that he received no money so far because the construction did not start. In the end, only one of Burck's suggestions was implemented: protecting the east border of Sachsenhausen using a roundel. Because of further delays by the city council, mid-1624, a dispute ensued, ending in February 1625 with the dismissal of Burck with a redundancy payment of 125 thaler.

Commission of Johann Wilhelm Dilich

Word about the city council's intention to improve Frankfurt's fortification had spread. Renowned fortress architect Johann Wilhelm Dilich, working in Kassel at the time, sent a letter to the council on 16 December 1624, offering his services. At the same time, he provided a commented architect's plan, emphasizing that he did not consider the old city wall to be sufficiently strong to serve as a middle wall for the planned bastions. The city council, believing that there was currently no need for such measures due to a lack of military threats, chose to ignore these concerns. When the army of Albrecht von Wallenstein left Bohemia in the direction of Franconia and Hesse, the city major, Johann Martin Baur von Eysseneck, mentioned Frankfurt-born Johann Adolf von Holzhausen as possible fortress architect. Holzhausen had been a sea captain in Mannheim.

The city council immediately commissioned captain Holzhausen to improve the defense of the Friedberger Tor (gate of Friedberg), which had considered to be the weakest part of the city fortification for a long time. At its position, there was a hill, and the gate was located at a protruding corner of the city wall. A dam allowed passage above the moat. In case of an attack, this construction would not have been properly defendable. Holzhausen turned in a plan for the construction of a Ravelin, an independent bastion in front of the city gate. In the end of 1626, the construction work began, but problems became apparent soon, caused by the captain's lack of experience. As already expected by Dilich, the outer ward was too weak to support the construction of a parapet behind it. Parts of the wall shattered and fell into the moat. In the other direction, gardens were buried by the dirt, leading to protests by the gardens' owners.

Due to a recommendation from book printer Clement Schleich from Wittenberg, the city council then asked Dillich's father, kurfürstlich-sächsisch engineer Wilhelm Dilich, for help.[48] He arrived in Frankfurt with his son in 1627 to get an overview of the situation. In his assessment, like his son, he rejected any reuse of the old fortification. Similar to Adam Stapf's plan, he recommended creating a regular, circular fortification with some distance to the city. In terms of planning, this would have been the easiest option, as all bastions and walls would have been of the same size. However, to be able to construct a wall in such distance, the city would have been required to buy new land. The city council declined this idea, and demanded four other proposals with walls closer to the city. All of these were considered to be too expensive as well, so father and son departed in the beginning of April.

When, in the middle of 1627, Holzhausen's ravelin completely collapsed, the fortress architect, apparently in despair, appealed the city council to commission Johann Wilhelm Dilich with the task.[49] Until Dilich rearrived in October, however, Holzhausen further did more damage than good, by ordering the dirt of the collapsed structure to be moved near the Pestilenzhauses behind the city wall. Again, multiple gardens were severely damaged in the process.

Dilich, who had obtained an overview during the winter months, was commissioned as Stückmajor for the city on 8 January 1628. In the council session of 22 February, a very contentious debate ensued about his plans to considerably extend the fortification. Despite the eventual negative stance, the problematic results of Holzhausen's failed construction attempts still existed in form of approximately 3000 wheelbarrow loads of dirt on both sides of the city wall. Mostly due to a lack of any other solution, Dilich was allowed to improve the old city wall at its weakest positions north of the city wall, by constructing two bulwarks in front of the Eschenheimer Tor (gate of Eschenheim) and the Friedberger Tor (gate of Friedberg), using the dirt of the collapsed ravelin. To hedge the project against political concerns, during the cornerstone ceremony on 16 June 1628, city major Johann Martin Baur of Eysseneck solemnly declared that the new fortification was not directed against emperor and empire, but rather meant to protect the loyal city.

Further false economy by the city council led to another collapse of larger parts of the wall that were still under construction, mid-1629. Because of the opinion(likely the council's opinion, not Dilich's, translator's note) that the Friedberger Tor had to be protected first, Dilich had to build the first bulwark there instead of beginning his construction at the deepest position of the city, at the Main riverbank, as would have been required for drainage reasons. Furthermore, to avoid damaging the fields, he was required to build on the old, completely swamped moat, leading to static problems and ultimately to a collapse. During the subsequent investigation, Dilich, Nikolaus Mattheys from Mannheim who had been commissioned as a wall master on Dilich's recommendation, and the craftspeople cast the blame on each other. According to Dilich, the wall master allegedly had spent more time in pubs than doing his job (German text: "'mehr der Bierhütte als des Walles' zugesprochen"), and the construction workers had supposedly snored in Dilich's direction ("Dilich 'angeschnarcht'", perhaps "in Dilich's presence" would be more fitting, translator's note). In the end, only Mattheys was dismissed and replaced by Johann Zimmermann from Mainz. No offence was proven against the craftspeople, and Dilich's commission was upheld as well.

Again, an external reviewer, fortress architect and mathematician Johannes Faulhaber from Ulm, was called in. He pointed out the already-known problems, but also noticed additional errors in Dilich's plans, corrected them and openly rebuffed Dilich in front of the city council, lecturing that Dilich's father had done better than Dilich, but that, in Faulhaber's opinion, Dilich himself apparently did not want to learn or change his views anymore. Faulhaber managed to powerfully prove his criticism using algebraic calculations and a paper model. After Faulhaber left the city in March 1630, Dilich followed his recommendations, causing the construction works to make good progress from that moment on. Already in June, the collapse damages were fixed.

At times, up to 600 people worked on the wall. In 1631, master builder Matthias Staudt from Darmstadt was assigned as Dilich's assistant. The citizenry were required to pay an exceptional Schatzung, id est a special tax, for the construction of the wall. They also were enlisted for compulsory labor, which led to a petitionary letter from the Lessing-Gymnasium's teachers, requesting to be exempted from the labor to be able to meditate at day and night and to be able to do trade business in addition to their work to be able to make a living. The city council declined the request. While engineer Dilich received a municipal salary of 448 guilder per year, the teachers received only 50.

Fortification

Dilich utilized Dutch fortress architecture, an enhanced successor of the Italian fortress architecture. He kept the old walls in place and created new moats in a distance of approximately 30 metres in front of the existing fortification. Following this, he used the dug-out soil to create an earth wall in front of the stonework. Sometimes, he filled the old moat in the process; in some cases, he created a new moat in front of the old one. The main advantage over the old construction style was that Dutch-style earth walls, contrary to Italian-style stone walls, were not noticeably susceptible to cannon damage. The moats prevented hostile wall climbing. A hand drawing by Dilich shows his construction style: From the inside to the outside, there were an outer ward between the walls, the stone walls, the earth rampart, the fortified breastwork, at its base the Faussebraye with another breastwork, then the escarpe wall(de:Eskarpemauer, fr:Escarpe, es:Escarpa_(fortificación), nl:Escarpe, hr:Eskarpa, pl:Skarpa_(wojsko), ru:Эскарп, sv:Fortgrav, yes, we do surprisingly still need an article or redirect, translator's note!), the wet moat, the Contrescarpe, and finally a glacis, partially with palisades on top. From the pentagonal bastions, it was possible to rake the glacis and the wall front with artillery fire.

However, in this specific style, as for example a comprehensive drawing by Matthäus Merian from 1645 shows, the construction was only done between the Eschenheimer Tor (gate of Eschenheim) and the Allerheiligentor (all hallows' gate). Based on the bad experience from previous construction attempts, the line of new fortification was soon moved 15 metres to the outside. This preserved the original medieval wall with the moat behind it. One benefit of this decision was the existence of a wet moat on both sides of the fortification, rendering the walls inaccessible by any other paths than a few bridges.

Dilich's work was planned to be halted by the city council in December 1631 due to a shortage of money. However, when the Swedes entered the city on 20 November under command of king Gustavus Adolphus of Sweden, they set the construction work in motion. Swedish town major Oberst Vitzthum ordered his soldiers to assist with the fortification. Beginning in May 1632, three new bulwarks were constructed: The bulwark at the Breiter Wall (wide wall) was also called Swedes' bulwark (Schwedenbollwerk) because it was constructed by the Swedish soldiers. The Bauernbollwerk (farmers' bulwark) at the Eschenheimer Tor (gate of Eschenheim) was a result of compulsory labor by farmers from Frankfurt's villages. The city military of Frankfurt constructed the Bockenheimer Bollwerk (bulwark of Bockenheim) at the Bockenheimer Tor (gate of Bockenheim).

When it became known that the emperor's army was approaching, already in August 1632, the construction of three further bulwarks began. Under Swedish pressure, the city council decided that for these constructions, each day, two-quarters of the citizens, as well as 150 Jewish citizens, were to be drafted for compulsory work. The presence of the military influenced the organization: By a drummer, the citizens of the quarters that had a turn were called to the front of the Bürgerkapitän's (citizens' captain's) house early in the morning. Many wealthier people sent their farmworkers or maids instead to avoid the compulsory work, and let them dance to the beat of the drums. This displeased the Swedish military personnel, but the city council did not forbid it, to keep the populace entertained and willing to work ("um das Gesindlein lustig und willig zur Arbeit zu erhalten").

The further expansion of the fortification dragged on until long after the Peace of Westphalia. The digging of the moats and the basic foundation of the bulwarks and the curtain walls were already mostly completed around 1645; during the following years, the work mostly focused on the construction of the outer moat revetment wall and the raising of the Feldbrustwehr (field breastwork). Especially the latter work took a long time to be finished using the tools that were available in the era. When Dilich died in 1660, Stückmajor Andreas Kiesser continued the work. In 1667, 49 years after the beginning of the construction, the work was essentially completed. North of the Main, a total of 11 bastions now surrounded the city, while the much smaller Sachsenhausen was protected by five bastions. For the first time, the Fischerfeld (fishers' field) became encompassed by the city fortification.

The 11 bastions, from east to west, were named: Fischerfeldbollwerk (fishers' field bulwark, construction started in 1632), Allerheiligen- or Judenbollwerk (all hallows' bulwark or Jews' bulwark, at the Allerheiligentor / all hallows' gate, construction started in 1632), Schwedenschanze or Breitwallbollwerk (Swedes' sconce or wide wall bulwark, construction started in 1632), Pestilenzbollwerk (pestilence bulwark, at the Klapperfeld, where the Pestilenzhaus was located and today's Landgericht Frankfurt am Main is located, construction started in 1631), Friedberger Bollwerk (bulwark of Friedberg, at the Friedberger Tor / gate of Friedberg, construction started in 1628), Eschenheimer Bollwerk (bulwark of Eschenheim, at the Eschenheimer Tor / gate of Eschenheim, construction started in 1631), Bauernbollwerk (farmers' bulwark, construction started in 1632), Bockenheimer Bollwerk (bulwark of Bockenheim, at the Bockenheimer Tor / gate of Bockenheim, construction started in 1632), Jungwallbollwerk (young wall bulwark, construction started in 1632), Galgenbollwerk (gallows' bulwark, construction started in 1635), and Mainzer- or Schneidwallbollwerk (bulwark of Mainz or sawmill bulwark, construction started in 1635, work restarted almost from scratch in 1663 and 1664 due to most severe construction damage).

Around Sachsenhausen, there were the Tiergartenbollwerk (zoological garden bulwark) at the eastern Main river bank (construction started in 1635); the Hohes Werk (high bulwark) at the south-east corner (construction started in 1648, final appearance formed in 1665); the Hornwerk (horn bulwark) at the Affentor (ape gate), originally built in crescent-shaped form from 1631 to 1635, reconstructed to its final appearance in 1665 and 1666); the Oppenheimer Bollwerk (bulwark of Oppenheim) west of the former Oppenheimer Pforte (gate of Oppenheim), no information known for sure, likely built in crescent-shaped form around 1635 and later reinforced; and the Schaumainkaibollwerk (crescent-shaped construction in 1639, converted to its new form in 1667) at the Schaumainkai (look-(at-)Main pier).

Because some of the bastions had been raised directly in front of the Landtore (land gates), these also had to be modified or reconstructed. In summary, it is striking that the new buildings, mostly early-baroque-styled, were rather plain. One possible explanation is that the pure engineering work of the bastioning were such a large burden on the city coffers that there had been no money for elaborated, representative gate designs. The Galgentor (gallows' gate) remained in its medieval form and was soon called the "Altes Galgentor" (old gallows' gate), in order to distinguish it from the Neues Galgentor (new gallows' gate) constructed from 1661 to 1662 further south, between the Galgenbollwerk (gallows' bulwark) and the Mainzer Bollwerk (bulwark of Mainz). The new gate was accessible via a drawbridge above the new city moat.

At the Bockenheimer Tor (gate of Bockenheim) itself, which had already been modified in 1605, nothing changed. To restore access, the bridge in front of it was simply expanded to fit above the new city moat. Although not necessary due to a newly constructed bastion in front of it, the Eschenheimer Tor (gate of Eschenheim) received new gate buildings in 1632 and 1633 as well. Compared to the others, they may have been the most representative ones, decorated with volute ornaments and richly profiled windows and gates, of which the foremost gate was adorned by a Reichsadler between antique-like acroteria. In contrast, the Altes Friedberger Tor (old gate of Friedberg) was converted to a simple wall tower, having become redundant to the same-named new bastion in front of it. The Neues Friedberger Tor (new gate of Friedberg), with a design possibly best comparable to that of the Galgentor (gallows' gate), was constructed from 1628 to 1630 at the north-eastern end of the Vilbeler Gasse (today's Vilbeler Straße). Eventually in 1636, the Allerheiligentor (all hallows' gate), which did not provide access to anything else than the same-named bulwark anymore, was superseded by a reconstruction in the north.

Consequences of the Thirty Years' War

A cost-benefit evaluation of Frankfurt's fortification is a difficult task. Its construction was a severe burden to the city's finances. Despite the fortification, Frankfurt was occupied by Swedish troops from 1631 to 1635. The latent tensions escalated on 1 August 1635 when Swedish troops in Sachsenhausen attempted to gain control over the city.

Consequently in turn, the city council allowed the emperor's troops, commanded by Freiherr Guillaume de Lamboy, Baron of Cortesheim, to enter the city at the northern Main side. Entrenched in both parts of the city, severe battles ensued, causing enormous damage. Among other collateral damage, the Brückenmühle (bridge mill) and almost the complete Löhergasse in Sachsenhausen was destroyed. Probably only due to Vizthum's judgement and decision to enter negotiations with Lamboy, a calamity in form of a large fire destroying the whole city, could barely be prevented. On 10 August, as a result of the conversation, the Swedes were granted safe conduct with military honors in the direction of Gustavsburg.

Especially severe damages were caused by the black death years 1634 to 1636. In 1634, 3512 people died in Frankfurt, in 1635, 3421 died, and 1636 claimed 6943 lifes.[50] The city population since the Middle Ages never exceeded 10,000 to 13,000 people, so the high death rate is only explainable by the number of people who had fled to Frankfurt as a refuge from the horrors of war. Despite all stresses and strains, Frankfurt, contrary to other south-German cities like Mainz or Nuremberg, retained its political importance and quickly recovered from the economic consequences of war.

Planungsfehler und Bauschäden

Already during the construction works, but mostly in the end of the 17th and in the 18th century, repeatedly, individual parts of the fortification required expensive maintenance repairs. For this reason, the municipal bill books even after 1667 rarely contained any year entry with less than thousands, and often far more than ten thousand, guilder of "fortification construction" ("Fortifikationsbau") costs.[51] Almost always, this was caused by errors that had been made during the fortification's construction. The construction had been done in wrong places and not with due munificence. This was caused by false economy and overcaution in regards to the fields("Feldgüter". Is "fields" an appropriate translation? Translator's note) that had been necessary(Should the literal translation "fields that had been necessary", "nötig (gewesene) Feldgüter", be replaced by "fields that had to be purchased"? This seems to be about the necessity of purchasing land for the wall to be placed on. Translator's note) for the construction.

One of the main errors had been made in the early years of the construction works: The first part of the baroque fortification had been built on too-swampy ground instead of the lowest point at the lower Main riverbank, where draining the incoming water would have been a trivial task. In nearly all bolwarks, this resulted in structural, fundamental damages that were almost impossible to repair properly. To make matters worse, all involved parties apparently lacked professional expertise to correctly assess the required thickness of the foundation. And finally, the construction was done too hastily during the presence of Swedish troops.

The city council repeatedly reduced the payment of the engineers below the requested amount, inevitably negatively affecting the quality of the manual work. Apparently, during the whole 17th century, there was not a single council member with the required competence to evaluate the quality of the work, making the council dependent on frequent invocation of expert witnesses. Also, none of the expert witnesses, of whom Faulhaber certainly was the most capable, noticed a fundamental misplanning: The shoulders of the bastions were perpendicular to the middle wall, forming a square angle instead of an obtuse angle, the latter of which would have been required for them to mutually rake the moat(with cannon fire, for example, translator's note) in front of each other in case of an attack.[52] Incorrect, as well, was the construction of merlons on the front of the bulwarks instead of the center of the middle walls. The resulting blind angles would have allowed attackers to unopposedly bombard the city from the Mühlberg or the Affenstein, like before in 1552.

Over the 18th century, due to fast-paced military research and development, the city fortification ultimately lost its defensive value. Instead, the townspeople began to use the publicly accessible walls as a local recreational area. Around 1705, the first lime trees were planted at the ramparts; beginning in 1765, a continuous avenue surrounded Frankfurt and Sachsenhausen.

During the Seven Years' War, the city was occupied by french troops, and its inhabitants were made to pay significant "contributions" taxes (Kontributionen). Also, during the Coalition Wars, the city fortification did not provide protection anymore. On the contrary, it turned out to be dangerous, as the fortified city was in danger of bombardment.

Deconstruction in the 19th century

Occupation of the city and first steps until 1806

In October 1792, french troops occupied the city. While allied troops from Hesse and Prussia managed to expel the invadors on 2 December 1792, the expulsion itself clearly proved the fortification useless: The allied soldiers easily managed to take the Friedberger Tor (gate of Friedberg) by storm. In 1795 and 1796, hostile troops arrived in front of the city again. Against the defense of Austrian troops, French aggressors bombarded the city, inflicting severe damage on 13 and 14 July 1796. A third of the Frankfurter Judengasse, which had burned down in a large fire in 1721, was destroyed again.

Subsequently, the Senate ordered the creation of plans for the slighting of the fortification. The idea to do so, however, came from outside the city, and the recommendation was unlikely made for purely altruistic motives. Via Frankfurt's ambassador in Paris, the French government suggested that the city could destroy its fortification to prevent being misappropriated as an arms depot and military base by hostile soldiers. While Frankfurt, like the other six remaining free imperial cities, had been assured military neutrality, the senate did fear being forced to implement the suggested deconstruction in case of war. This fear eventually became the reason for the slighting.[53]

Just like almost two centuries ago, the planning process for the defortification extended over a long period of time, and the senate ordered a plethora of methods to be considered and calculated.[54] Many of the plans only provided for the deconstruction of the bulwarks, deliberately preserving the 14th century's city wall as a protection against criminals and as a border control for people and goods.[55] As with the medieval fortification, the high-cost estimation caused the politicians to refuse agreeing on a comprehensive plan. In 1804, after almost 20 months of discussion, the deconstruction was slowly and halfheartedly begun by 50 to 60 day laborers. An expert report of summer 1805 stated that, when done at a continuous speed, the defortification was expected to take at least nine more years.[56]

Prince primate Dalberg and commission of Guiollett

Only in January 1806, when French soldiers occupied the city again, the project gained new traction. At the same time, the Senate asked the population to help with the demolition, resulting in unexpectedly high participation – probably also due to the imminent danger of the Austrian-French war.[57] With the end of the Holy Roman Empire in August 1806, the free imperial city Frankfurt lost its independence. It became part of the territory of Karl Theodor Anton Maria von Dalberg, prince primate.

On behalf of Dalberg, Jakob Guiollett formulated a memorandum "Notice Regarding the Slighting of Local Fortifications" ("Bemerkung über die Schleifung hiesiger Festungswerke"), released 5 November 1806. It recommends the demolition of Frankfurt's fortification as well as the construction of a promenade and an English landscape garden, today's Wallanlagen, in place of the bulwarks. On 5 January 1807, the prince primate appointed him as the princely commissioner of the fortification demolition that is to be continued ("Fürstlichen Commissarius bei dem fortzusetzenden hiesigen Festungsbau-Demolitions-Geschäfte").[58]

Guiollett enlisted castle gardener Sebastian Rinz from Aschaffenburg for the planning of the works. In the subsequent years, one after another, the Bockenheimer Anlage (1806), the Eschenheimer Anlage (1807), the Friedberger Anlage (1808/1809) as well as the Taunus- and Gallusanlage (1810) were constructed. Demolishing the mighty Mainzer Bollwerk (bulwark of Mainz) required a lot of effort from 1809 to 1818.[59] On the premises, in 1811, the Untermainanlage and the Neue Mainzer Straße were built. In 1812, Rinz completed the work with the Obermainanlage. All parts of the fortification except the Sachsenhäuser Kuhhirtenturm and the Eschenheimer Turm were deconstructed; only a few gates from the 15th century at the Main river bank, including the mighty Fahrtor, still remained in place. They were deconstructed in 1840, when the Main river bank was raised by two metres.

The citizens considered the demolition of the old walls to be the sign of a historical turning point. Katharina Elisabeth Goethe delightedly wrote to her son Johann Wolfgang von Goethe on 1. Juli 1808: