Castile and León: Difference between revisions

ILoveCaracas (talk | contribs) |

ILoveCaracas (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 276: | Line 276: | ||

Much of the Province of [[Salamanca]], especially in the districts of [[Campo Charro]] and [[Comarca de Ciudad Rodrigo]], is occupied by [[dehesa]]s, a type of forest similar to that of the African savannas, with evergreen oaks, [[Quercus suber|cork oak]]s, quercus faginea and pyrenean oaks. The Province of Salamanca and that of [[Province of Valladolid|Valladolid]] in the region of [[Rueda, Valladolid|Rueda]] also has the only Castilian-Leonese [[olive grove]]s, since these trees do not grow in any of the other regions of the community. Also noteworthy are the wine regions with very good quality wines such as those from [[Toro, Zamora|Toro]], those from [[Ribera del Duero (comarca)|Ribera del Duero]] (Valladolid, Burgos, Soria) those from [[Rueda, Valladolid|Rueda]], or those of [[Cigales]]. |

Much of the Province of [[Salamanca]], especially in the districts of [[Campo Charro]] and [[Comarca de Ciudad Rodrigo]], is occupied by [[dehesa]]s, a type of forest similar to that of the African savannas, with evergreen oaks, [[Quercus suber|cork oak]]s, quercus faginea and pyrenean oaks. The Province of Salamanca and that of [[Province of Valladolid|Valladolid]] in the region of [[Rueda, Valladolid|Rueda]] also has the only Castilian-Leonese [[olive grove]]s, since these trees do not grow in any of the other regions of the community. Also noteworthy are the wine regions with very good quality wines such as those from [[Toro, Zamora|Toro]], those from [[Ribera del Duero (comarca)|Ribera del Duero]] (Valladolid, Burgos, Soria) those from [[Rueda, Valladolid|Rueda]], or those of [[Cigales]]. |

||

==== Fauna ==== |

|||

[File:Arribesdeldueropozo.jpg|thumb|[[Arribes del Duero Natural Park]], which is a [[Special Protection Area|special protection area for birds]].]] |

|||

Castile and León presents a great diversity of fauna. There are numerous species and some of them are of special interest because of their uniqueness, such as some endemic species, or because of their scarcity, such as the [[brown bear]]. There have been counted 418 species of vertebrates, which make up 63% of all vertebrates that live in Spain. Animals adapted to life in the high mountains, inhabitants of rocky places, inhabitants of fluvial courses, species of plains and forest residents form the mosaic of the Castilian-Leonese fauna. |

|||

The isolation to which the high summits are subject leads to the existence of abundant endemisms such as the [[Spanish ibex]], which in Gredos constitutes a unique subspecies in the Peninsula. The [[European snow vole]] is a graceful small [[mammal]] of grayish brown color and long tail that lives in open spaces over the limit of the trees. |

|||

Small and large mammals such as [[squirrel]], [[dormouse]], [[Talpidae|talpids]], [[European pine marten]], [[Beech marten]], [[fox]], [[wildcat]], [[wolf]], quite abundant in some areas, [[boar]], [[deer]], [[roe deer]] and, only in the Cantabrian Mountains, some specimens of [[brown bear]] tend to frequent the deciduous forests, although some species also extend to coniferous forests and scrubland. The wildcat is slightly larger than a domestic cat, has a short and stout tail, with dark rings and striped fur. The [[Iberian lynx]], however, lives almost exclusively in areas of Mediterranean scrubland. |

|||

[[File:Canis lupus signatus (Kerkrade Zoo) 02.jpg|thumb|left|Castile and León is the main habitat of the [[Iberian wolf]]. The naturalist [[Félix Rodríguez de la Fuente]] promoted the protection of the species.]] |

|||

Small reptiles such as the [[ladder snake]], the [[coronella girondica]] and the [[aesculapian snake]] are also found in this environment. The [[Coronella austriaca|smooth snake]] can be found from sea level to 1,800 m in height and in the community it tends to live on the heights. Further up, in the rocky areas of the subalpine floor at about 2,400 m altitude the [[Iberian rock lizard]] lives, one of the few reptiles adapted at this point. |

|||

In the mountain rivers live the [[otter]] and [[desman]] and in its waters the [[trout]], [[anguillidae]], the [[common minnow]]s and some of the increasingly scarce autochthonous river crabs. The otter and the desman are two mammals with aquatic habits and very good swimmers. The [[otter]] feeds mainly on fish, while the desman seeks its food among the aquatic invertebrates that inhabit the riverbed. In lower sections of calmer waters swim [[barbel]] s and [[carps]]. Among the amphibians, the [[salamander]]s and as remarkable species: the Almanzor's [[salamander]] (''Salamandra salamandra almanzoris'') and the [[Gredos' toad]] (''Bufo bufo gredosicola''), which are two endemic subspecies to the Sistema Central. |

|||

== Regional administration and government == |

== Regional administration and government == |

||

Revision as of 03:32, 8 January 2018

Castile and León

[Castilla y León] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) Template:Es icon Castiella y Llión (in Leonese) [Castela e León] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) Template:Link language | |

|---|---|

| [Castilla y León] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) Template:Es icon | |

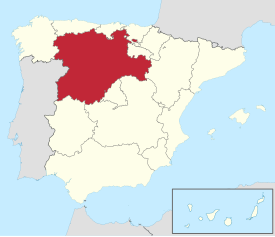

Location of Castile and León within Spain | |

| Coordinates: 41°23′N 4°27′W / 41.383°N 4.450°W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Capital | Undeclared (Valladolid de facto[1]) |

| Government | |

| • President | Juan Vicente Herrera (PP) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 94,222 km2 (36,379 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 1st (18.6% of Spain) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 2,447,519 |

| • Density | 26/km2 (67/sq mi) |

| • Pop. rank | 6th |

| • Percent | 5.42% of Spain |

| Demonym | |

| ISO 3166-2 | CL |

| Official languages | Spanish (Leonese and Galician have special status) |

| Statute of Autonomy | 2 March 1983 |

| Parliament | Cortes of Castile and León |

| Congress seats | 31 (of 350) |

| Senate seats | 39 (of 266) |

| Website | Junta de Castilla y León |

Castile and León (/kæˈstiːl ... liˈɒn/; Spanish: Castilla y León [kasˈtiʎa i leˈon] ; Leonese: Castiella y Llión [kasˈtjeʎa i ʎiˈoŋ]; Galician: Castela e León [kasˈtɛla e leˈoŋ]) is an autonomous community in north-western Spain. It was constituted in 1983, although it existed for the first time during the First Spanish Republic in the 19th century. León first appeared as a Kingdom in 910, whilst the Kingdom of Castile gained an independent identity in 1065 and was intermittently held in personal union with León before merging with it permanently in 1230. It is the largest autonomous community in Spain and the third largest region of the European Union, covering an area of 94,223 square kilometres (36,380 sq mi) with an official population of around 2.5 million (2011).

From the beginning of the federalist debate in Spain in the 19th century during the First Spanish Republic there were projects of autonomy for a Castile and León region, as the project of Castilian Mancomunity, Bases de Segovia, Castilian Provincial League or Castilian Federal Pact, but also including current Cantabria and La Rioja.[2][3] Same project that continued to exist during the Second Spanish Republic[4][5] and that was finally carried out after the Constitution of 1978 , but without Cantabria and La Rioja that, although it was considered to include them, finally formed uniprovincial autonomies.

Its Statute of Autonomy declares in its preamble:

The Autonomous Community of Castile and León arises from the modern union of the historical territories that composed and gave name to the old crowns of León and Castile. Eleven hundred years ago, the Kingdom of León was constituted, from which that of Castile and Galicia were dislodged as kingdoms throughout the 9th century, and, in 1143, that of Portugal. During these two centuries the monarchs who held the government of these lands attained the dignity of emperors, as attested by the terms of Alfonso VI and Alfonso VII.[6]

In Castile and León, more than 60% of all of Spain's heritage sites are found (architectural, artistic, cultural, etc.).[7] All of which translate into: 8 World Heritage sites, almost 1800 classified cultural heritage assets, 112 historic sites, 400 museums, more than 500 castles, of which 16 are considered of high historical value, 12 cathedrals, 1 concathedral, and the largest concentration of Romanesque art in the world. With 8 World Heritage sites, Castile and León is the region of the world with more cultural assets distinguished by the highest protection figure granted by Unesco, ahead of the Italian regions of Tuscany and Lombardy, both with 6 sites.[8] [9]

Also, the Montes de Valsaín mountains and the Béjar and Francia mountain ranges, in the Sistema Central, the valleys of Laciana, Omaña y Luna and the Picos de Europa and Los Ancares, in the Cantabrian Mountains, and the Iberian Plateau, in the border area with Portugal, have been declared biosphere reserve by UNESCO, which also recognizes the geopark of La Lora with this figure of protection.[10] In addition, Castile and León is strongly related to two of the records of the Memory of the World Programme of UNESCO which are the Decreta of the Cortes of León of 1188, curia regia considered the birthplace of worldwide parliamentarism by the institution itself,[11] and the Treaty of Tordesillas.[12]

The Index of development of social services reflects that the community has one of the best social services in the country, positioning itself as the third autonomy that offers the best benefits to its citizens, after the Basque Country and Navarre.[13] Its education, according to the Programme for International Student Assessment report of 2015, leads the scores in reading and sciences with a score comparable to that of the ten best countries in the study.[14]

23 April is designated Castile and León Day, commemorating the defeat of the comuneros at the Battle of Villalar during the Revolt of the Comuneros, in 1521. [citation needed]

Symbols

The Statute of Autonomy of Castile and León, reformed for the last time in 2007, establishes in the sixth article of its preliminary title the symbols of the community's exclusive identity. These are: the coat of arms, the flag, the banner and the anthem. Its legal protection is the same as that corresponding to the symbols of the State -whose outrages are classified as crime in article 543 of the Penal Code-.[6][15]

In the articulated statuary, the coat of arms is defined as follows:[6]

The coat of arms of Castile and León is a stamped shield by open royal crown, barracked in cross. The first and fourth quartering: in the field of gules, a merloned golden castle of three merlons, drafted of sable and rinse of azure. The second and third quartering: in a silver field, a rampant lion of purple, lingued, dyed and armed with gules, crowned with gold.

Likewise, the flag is described as follows:[6]

The flag of Castile and León is quartered and contains the symbols of Castile and León, as described in the previous section. The flag will fly in all the centres and official acts of the Community, to the right of the Spanish flag.

Following the same wording, the banner is constituted by the shield quartered on a traditional crimson background. The Statute also expresses: "The anthem and the other symbols [...] will be regulated by specific law". After the promulgation of the fundamental norm, this law was not promulgated, so the anthem does not exist, but de iure is a symbol of autonomy.[6]

History

The autonomous community of Castile and León is the result of the union in 1983 of nine provinces: the three that, after the territorial division of 1833, by which the provinces were created, were ascribed to the Region of León and six attached to the Old Castile, except in the latter case the provinces of Santander (current community of Cantabria) and Logroño (current La Rioja).

In the case of Cantabria the creation of an autonomous community was advocated for historical, cultural and geographic reasons, while in La Rioja the process was more complex due to the existence of three routes, all based on historical and socio-economic reasons: union with Castile and León (Union of the Democratic Centre), union to a Basque-Navarrese community (Socialist Party and Communist Party) or creation of an uniprovincial autonomy, option taken before the majority support of its population.

Several are the archaeological findings that show that in prehistoric times these lands were already inhabited. In the Atapuerca Mountains have been found many bones of the ancestors of Homo sapiens, making these findings one of the most important to determine the history of human evolution. The most important discovery that catapulted the site to international fame was the remains of Homo heidelbergensis.

Before the arrival of the Romans, it is known that the territories that make up Castile and León today were occupied by various Celtic peoples, such as vaccaei, autrigones, turmodigi, the vettones, astures or celtiberians.

With the arrival of the Roman troops, confrontations took place between the pre-Roman peoples and these. In the history remains the resistance of Numantia, near the current Soria.

The romanization was unstoppable, and to this day great Roman works of art have remained, mainly the Aqueduct of Segovia as well as many archaeological remains such as those of the ancient Clunia , Salt mines of Poza de la Sal and vía de la Plata, originating in Astorga (Asturica Augusta) and that crosses the west of the community to the capital of Extremadura, Mérida (Emerita Augusta).

With the fall of Rome, the lands were occupied militarily by the Visigoth peoples. The subsequent arrival of the Muslims and the subsequent reconquista have a lot to do with the current ethnic composition of the Iberian Peninsula. In the mountainous area of the current Asturias a small Christian kingdom was formed that opposed the Islamic presence in the Peninsula. They proclaimed themselves heirs of the last Visigoth kings, who in turn had been deeply romanized. This resistance of Visigoth-Roman heritage and supported by Christianity, was becoming increasingly strong and expanding to the south, passing its capital to the city of León and thus creating the Kingdom of León. To favor the repopulation of the new reconquered lands, were granted by the monarchs fueros or letters of repopulation.

In the Middle Ages the pilgrimage by Christianity to Santiago de Compostela was popularized. The Camino de Santiago runs throughout the region, which contributed to European culture traveling and expanding throughout the peninsula. Today that Camino is still a tourist and cultural claim of the first order.

In 1188 the basilica of San Isidoro of León had been the seat of the first parliamentary body of the history of Europe in 1188, with the participation of Third Estate. The king who summoned them was Alfonso IX of León.

The legal basis was the Roman law, due to which the kings increasingly wanted more power, like the Roman emperors. This fact is very clearly seen in the Siete Partidas of Alfonso X of Castile, which makes clear the imperial monism that he sought. The King did not want to be a primus inter pares, the king was the source of the law.

Simultaneously, a county of this Christian kingdom of León, begins to acquire autonomy and to expand. This is the primitive County of Castile, which will grow into a real kingdom of great strength among the Christian kingdoms of the Peninsula. The first Castilian count was Fernán González.

León and Castile continued to expand to the South, even beyond the Douro with its purpose of struggle and reconquest against Islam. We are in the middle of the Middle Ages and the songs of deed tell of the great deeds of the Christian nobles who fought against the Muslim enemy. Despite this, Christian and Muslim kings maintained diplomatic relations. Clear example is Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, El Cid, paradigm of the medieval Christian knight, who fought both hand of Christian kings and Muslims.

The bases of the dynastic unification of the kingdoms of Castile and León, separated by only seven decades, had been put in 1194. Alfonso VIII of Castile and Alfonso IX of León signed in Tordehumos the treaty that pacified the area of Tierra de Campos and laid the foundations for a future reunification of the kingdoms, consolidated in 1230 with Ferdinand III the Saint. This agreement has gone down in history as the Treaty of Tordehumos.

With Ferdinand III, Castile and León are united under the same kingdom in a definitive way and to this day, and before him the kingdoms had already remained under the same command for some seasons.

During the Late Middle Ages there was an economic and political crisis produced by a series of bad harvests and by disputes between nobles and the Crown for power, as well as between different contenders for the throne. In the Cortes of Valladolid of 1295, Ferdinand IV is recognized as king. The painting María de Molina presents her son Fernando IV in the Cortes of Valladolid of 1295 presides today the Congress of Deputies along with a painting of the Cortes of Cádiz, emphasizing the parliamentarian importance that has all the development of Cortes in Castile and León, despite its subsequent decline. The Crown was becoming more authoritarian and the nobility more dependent on it.

The reconquista continued advancing in this thriving Crown of Castile, and culminated with the surrender of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, last Muslim stronghold in the Peninsula.

The Catholic Monarchs shared the maritime routes and the New World with the Portuguese crown in the Treaty of Tordesillas.

Antecedents of autonomy

In June of 1978, Castile and León obtained the pre-autonomy, through the creation of General council of Castile and León by Royal Decree-Law 20/1978, of June 13.[19]

In times of the First Spanish Republic (1873-1874), the federal republicans conceived the project to create an federated state of eleven provinces in the valley of the Spanish Douro, that would also have included the provinces of Santander and Logroño.[20]Very few years before, in 1869, as part of a manifesto, federal republicans representatives of the 17 provinces of Albacete, Ávila, Burgos, Ciudad Real, Cuenca, Guadalajara, León, Logroño, Madrid, Palencia, Salamanca, Santander, Segovia, Soria, Toledo, Valladolid and Zamora proposed in the so-called Castilian Federal Pact the conformation of an entity formed by two different "states": the state of Old Castile -that is presently built for the current Castilian-Leonese provinces and the provinces of Logroño and Santander-, and the state of New Castile -which conforms to the current provinces of Castile-La Mancha plus the province of Madrid-. The end of the Republic, at the beginning of 1874, thwarted the initiative.[21]

In 1921, on the occasion of the fourth centenary of the Battle of Villalar, the Santander City Council advocated the creation of a Castilian and Leonese Commonwealth of eleven provinces, idea that would be maintained in later years. At the end of 1931 and beginning of 1932, from León, Eugenio Merino elaborated a text in which the base of a Castilian-Leonese regionalism was put. The text was published in the Diario de León newspaper.[4]

During the Second Spanish Republic, especially in 1936, there was a great regionalist activity favorable to a region of eleven provinces, and even bases for the Statute of Autonomy were elaborated. The Diario de León advocated for the formalization of this initiative and the constitution of an autonomous region with these words:

Join in a personality León and Old Castile around the great basin of the Douro, without to fall now into provincial rivalries.

— Diario de León, May 22, 1936.

The end of the Spanish Civil War and the beginning of Franco regime ended the aspirations of the autonomy for the region. The philosopher José Ortega y Gasset collected this scheme in his publications.[22]

After the death of Francisco Franco, regionalist, autonomist and nationalist organizations (Castilian-Leonese regionalism and Castilian nationalism) as Regional Alliance of Castile and León (1975), Regional Institute of Castile and León (1976) or the Autonomous Nationalist Party of Castile and León (1977). Later after the extinction of these formations arose in 1993 Regionalist Unity of Castile and León.[23]

At the same time, others of Leonesist character arose, such as the Leonese Autonomous Group (1978) or Regionalist Party of the Leonese Country (1980), which advocated the creation of a Leonese autonomous community, composed of provinces of León, Salamanca and Zamora. The popular and political support that maintained the uniprovincial autonomy in León became very important in that city.

After the entry into operation of the Castilian-Leonese pre-autonomous body, which was created by the Provincial Council of León in its agreement of April 16 of 1980, the same institution of León revoked in January 13 of 1983 its original agreement, just when the draft Organic Law entered into the parliament existence of contradictory agreements and which was valid was resolved by the Constitutional Court in the Sentence 89/1984 of September 28 in its foundation of law declares that the subject of the process is not already integrated, as in its preliminary phase, by the councils and municipalities, but it is a new body that is born because it has already manifested the driving will and expresses now that of the territory as a whole; and that will already has a different object, the future legal regime of the territory that has already manifested its will to become an autonomous community through initiatives that have exhausted its effects.

Coinciding with that sentence, there were several demonstrations in León, some of them numerous, in favor of the option only León, which according to some sources brought together a number close to 90 000 attendees,[24] This is the highest concentration held in the city in the Democracy until the subsequent rejection of the 2004 Madrid train bombings.[25]

In an agreement adopted on July 31, 1981, the Provincial Council of Segovia decided to exercise the initiative so that Segovia could be constituted as a uniprovincial autonomous community, but in the municipalities of the province the situation was equal between the supporters of the uniprovincial autonomy or with the rest of Castile and León.

The City Council of Cuéllar initially adhered to this autonomic initiative in agreement adopted by the corporation on October 5 of 1981. However, another agreement adopted by the same corporation dated December 3 of the same year revoked the previous one and the process was paralyzed pending the processing of an appeal filed by the provincial deputation against this last agreement this change of opinion of the city council of Cuéllar inclined the balance in the province towards the autonomy with the rest of Castile and León, but it was an agreement that arrived out of time. Finally the province of Segovia was incorporated into Castile and León along with the other eight provinces and legal coverage was given through the Organic Law 5/1983 for "reasons of national interest", as provided for in article 144 c of the Spanish Constitution for those provinces that have not exercised their right on time.

Today, the Villalar Foundation is responsible for the realization of cultural activities on the art, culture or identity of Castile and León.[26]

The community grants each year, on the occasion of the Castile and León Day, the Castile and León Awards to the Castilian-Leonese outstanding in the following areas: arts, human values, scientific research, social sciences, restoration and conservation, environment and sports.[27]

Geography

Location

Castile and León is an autonomous community with no exit to the sea that is located in the north-western quadrant of the Iberian Peninsula. Its territory borders on the north with the uniprovincial communities of the Principality of Asturias and Cantabria as well as with the Basque Country (Biscay and Álava); to the east with the uniprovincial community of La Rioja and with Aragon (province of Zaragoza), to the south with the Community of Madrid, Castile-La Mancha (provinces of Toledo and Guadalajara) and Extremadura (province of Cáceres) and to the west with Galicia (provinces of Lugo and Ourense) and Portugal.

Orography

The morphology of Castile and León is formed, for the most part, by the Meseta and a belt of mountainous reliefs. The plateau is a high plateau, which has an average altitude close to 800 m.a.s., is covered by deposited clay materials that have given rise to a dry and arid landscape.

Following the morphology of the area can be seen: to the north, the mountains of the provinces of Palencia and of León with high and spiky summits and the mountains of province of Burgos, divided into two parts by the Pancorbo gorge, link between the Basque Country and Castile. Of these, the northern part belongs to the Cantabrian Mountains and reaches the city of Burgos. The east-southeast zone, belonging to the Sistema Ibérico. In the northwest part the mountains of Zamora extend, with peaks inplateauted by the erosion. To the east, in the Soria mountains, you can see the Sistema Ibérico, presided over by the Moncayo Massif, its highest peak. Separating the northern plateau from the southern, to the south, the Sistema Central rises, where the mountain ranges of Gata, Francia, Béjar and Gredos in the western half and those of Ávila, Guadarrama, Somosierra and Ayllón in the eastern half.

Geology

The Northern Plateau (Meseta Norte) is constituted by Paleozoic sockets. At the beginning of the Mesozoic Era, once the Hercynian folding that raised the current Central Europe and the Gallaeci zone of Spain, the deposited materials were dragged by the erosive action of the rivers.

During the alpine orogeny, the materials that formed the plateau broke through multiple points. From this fracture rose the mountains of León, with mountains of not much height and, constituting the spine of the Plateau (Meseta), the Cantabrian Mountains and the Sistema Central, formed by materials such as granite or metamorphic slates.

The karst complex of Ojo Guareña, consisting of 110 km of galleries[28] and its caves formed in carbonatic materials of Coniacian which are situated on a level of impermeable marls, is the second largest of the peninsula.

This geological configuration has allowed upwellings of mineral-medicinal and/or thermal water, used now or in the past, in Almeida de Sayago, Boñar, Calabor, Caldas de Luna, Castromonte, Cucho, Gejuelo del Barro, Morales de Campos, Valdelateja and Villarijo, among other places.

Hydrography

Rivers

- Douro basin

The main hydrographic network of Castile and León is constituted by the Douro river and its tributaries. From its source in the Picos de Urbión, in Soria, to its mouth in the Portuguese city of Porto, the Douro covers 897 km. From the north descend the Pisuerga, the Valderaduey and the Esla rivers, its tributaries more plentiful and by the east, with less water in its flows, highlight the Adaja and the Duratón. After passing the town of Zamora, the Douro is confined between the canyons of the Arribes del Duero Natural Park, bordering with Portugal. On the left bank are important tributaries such as Tormes, Huebra, Águeda, Côa and Paiva, all from Sistema Central. On the right they reach the Sabor, the Tua and the Tâmega, born in the Galician Massif. After the Arribes area, the Douro turns west into Portugal until it empties into the Atlantic Ocean.

- Other watersheds

Several rivers of the community pour their waters into the Ebro basin, in Palencia, Burgos and Soria (Jalón river), that of Miño-Sil in León and Zamora, that of the Tagus in Ávila and Salamanca (rivers Tiétar and Alberche and Alagón respectively) and Cantabrian basin in the provinces through which the Cantabrian Mountains extends.

- Rivers and provincial capitals where they pass

| River | Capital | River mouth | Other locations where it passes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adaja | Ávila | Douro in Villamarciel | Tordesillas and Arévalo |

| Arlanzón | Burgos | Arlanza in Quintana del Puente | Arlanzón and Pampliega |

| Bernesga | León | Esla | La Robla |

| Carrión | Palencia | Pisuerga in Dueñas | Guardo and Carrión de los Condes |

| Tormes | Salamanca | Douro in Fermoselle | El Barco de Ávila, Guijuelo, Alba de Tormes and Ledesma |

| Eresma | Segovia | Adaja in Matapozuelos | Coca |

| Douro | Soria and Zamora | Atlantic Ocean in Porto | Almazán, Aranda de Duero, Tordesillas, Toro, Aldeadávila de la Ribera and Vilvestre |

| Pisuerga | Valladolid | Douro in Geria | Aguilar de Campoo, Cervera de Pisuerga, Venta de Baños, Dueñas, Tariego de Cerrato and Simancas |

After many centuries disappeared from the Iberian Peninsula, the European bison is being reintroduced in the region.[29]

Lakes and reservoirs

In addition to the rivers, the Douro basin also hosts a large number of lakes and lagoons such as the Negra de Urbión Lake, in the Picos de Urbión, the Grande de Gredos Lake , in Gredos, the Sanabria Lake, in Zamora or the La Nava de Fuentes Lake in Palencia. Also emphasize a great amount of reservoirs, fed by the water coming from the rains and the thaw of the snowy summits. Thus, Castile and León, despite not having abundant rainfall, is one of the communities in Spain with the highest level of water dammed.

Many of these natural lakes are being used as an economic resource, boosting rural tourism and helping to conserve ecosystems. The Sanabria Lake was a pioneer in this.

Climate

Castile and León has a continentalized Mediterranean climate, with long, cold winters, with average temperatures between 3 and 6 °C in January and short, hot summers (average 19 to 22 °C), but with the three or four months of summer aridity characteristic of the Mediterranean climate. Rainfall, with an average of 450-500 mm per year, is scarce, accentuating in the lower lands.

- Climatic factors

In Castile and León the cold extends almost continuously for much of the year, being a very characteristic element of its climate. The coldest periods of winter are associated with invasions of a continental polar front and strata of marine arctic air, rare is that they do not reach temperatures of the order of -5 ° to -10 °C. Likewise, in situations of anticyclone, in the interior of the region they cause persistent fogs, creating prolonged cold situations due to radiation processes. The intense "cold waves" of the winter central months are typical, showing a particular tendency to occur from the second fortnight of December to the first of February. During its course the most extreme minimum temperatures occur, whose values vary between -10 ° and -13 °C of its westernmost sector and -15 ° and -20 °C of the central plains and high moorlands. The lowest recorded records reach -22 °C of Burgos, -21.9 °C in Coca (Segovia), -20.4 °C in Ávila, -20 °C in Salamanca and -19.2 °C in Soria. The high altitude of the Meseta and its mountains accentuates the contrast between winter and summer temperatures, as well as day and night temperatures.[30]

Due to the mountainous barriers that surround Castile and León, the maritime winds are stopped, thus stopping the precipitations. Due to that, the rains fall in a very unequal way in the Castilian and Leonese territory. While in the middle of the Douro basin there is an annual average of 450 mm, in the western regions of the mountains of León, the Cantabrian Mountains and the southern area of the Provinces of Ávila and Salamanca, rainfall reaches 1500 mm per year, with a maximum of 3400 mm per year in the western part of the Sierra de Gredos, in the Candelario-Bejar Massif, which makes this area the rainiest not only from Spain, but from the Iberian Peninsula.[31]

- Climatic regions

Although Castile and León is framed within the continental climate, in its lands different climate domains are distinguished:[32]

- According to the Köppen climate classification, a large part of the autonomous community falls within the Csb or Cfb variants, with the average of the warmest month below 22 °C but above 10 °C for five or more months.

- In several areas of the Meseta Central the climate is classified as Csa (warm Mediterranean), by exceeding 22 °C during the summer.

- In high elevations of the Cantabrian Mountains and mountain areas, there is a cold temperate climate with average temperatures under 3 °C in the coldest months and dry summers (Dsb or Dsc).

Nature

Flora

Castile and León has many protected natural sites. Actively collaborates with the European Union program Natura 2000. There are also some special protection area for birds or SPA. The solitary evergreen oaks and junipers (Juniperus sect. Sabina) that now draw the Castilian-Leonese plain are remnants of the forests that covered these same lands long ago. The agricultural holdings, due to the need of land for the cultivation of cereal and pastures for the immense herds of the Castilian Plateau, supposed the deforestation of these lands during the Middle Ages. The last Castilian and Leonese forests of junipers are found in the Provinces of León, Soria and Burgos. They are not very leafy forests that can form mixed communities with evergreen oaks, quercus fagineas or pines.

The Castilian-Leonese slope of the Cantabrian Mountains and the northern foothills of the Sistema Ibérico have a rich vegetation. The most humid and fresh slopes are populated by large beechs, whose extension areas can reach 1,500 m altitude. In turn, the European beech forms mixed forests with the yew, the sorbus, the whitebeam, the European holly and the birch. On the sunny slopes the sessile oak, the European oak, the ash, the lime tree, the sweet chestnut, the birch and the scots pine (a typical species from the north of the Province of León).

On the lower slopes of the Sistema Central extensive extensions of holm oaks survive. At a higher level, between 1000 and 1100 masl, chestnut trees abound. Above them predominates the pyrenean oak, very resistant to the cold, whose stratum extends until the 1700 masl. However, many oak groves have disappeared, cut down by man and replaced by pine trees of repopulation. The main native pine forests are found in the Sierra de Guadarrama. The subalpine zones located between 1700 and 2200 masl are home to thickets of cytisus oromediterraneus and junipers.

Much of the Province of Salamanca, especially in the districts of Campo Charro and Comarca de Ciudad Rodrigo, is occupied by dehesas, a type of forest similar to that of the African savannas, with evergreen oaks, cork oaks, quercus faginea and pyrenean oaks. The Province of Salamanca and that of Valladolid in the region of Rueda also has the only Castilian-Leonese olive groves, since these trees do not grow in any of the other regions of the community. Also noteworthy are the wine regions with very good quality wines such as those from Toro, those from Ribera del Duero (Valladolid, Burgos, Soria) those from Rueda, or those of Cigales.

Fauna

[File:Arribesdeldueropozo.jpg|thumb|Arribes del Duero Natural Park, which is a special protection area for birds.]] Castile and León presents a great diversity of fauna. There are numerous species and some of them are of special interest because of their uniqueness, such as some endemic species, or because of their scarcity, such as the brown bear. There have been counted 418 species of vertebrates, which make up 63% of all vertebrates that live in Spain. Animals adapted to life in the high mountains, inhabitants of rocky places, inhabitants of fluvial courses, species of plains and forest residents form the mosaic of the Castilian-Leonese fauna.

The isolation to which the high summits are subject leads to the existence of abundant endemisms such as the Spanish ibex, which in Gredos constitutes a unique subspecies in the Peninsula. The European snow vole is a graceful small mammal of grayish brown color and long tail that lives in open spaces over the limit of the trees.

Small and large mammals such as squirrel, dormouse, talpids, European pine marten, Beech marten, fox, wildcat, wolf, quite abundant in some areas, boar, deer, roe deer and, only in the Cantabrian Mountains, some specimens of brown bear tend to frequent the deciduous forests, although some species also extend to coniferous forests and scrubland. The wildcat is slightly larger than a domestic cat, has a short and stout tail, with dark rings and striped fur. The Iberian lynx, however, lives almost exclusively in areas of Mediterranean scrubland.

Small reptiles such as the ladder snake, the coronella girondica and the aesculapian snake are also found in this environment. The smooth snake can be found from sea level to 1,800 m in height and in the community it tends to live on the heights. Further up, in the rocky areas of the subalpine floor at about 2,400 m altitude the Iberian rock lizard lives, one of the few reptiles adapted at this point.

In the mountain rivers live the otter and desman and in its waters the trout, anguillidae, the common minnows and some of the increasingly scarce autochthonous river crabs. The otter and the desman are two mammals with aquatic habits and very good swimmers. The otter feeds mainly on fish, while the desman seeks its food among the aquatic invertebrates that inhabit the riverbed. In lower sections of calmer waters swim barbel s and carps. Among the amphibians, the salamanders and as remarkable species: the Almanzor's salamander (Salamandra salamandra almanzoris) and the Gredos' toad (Bufo bufo gredosicola), which are two endemic subspecies to the Sistema Central.

Regional administration and government

Castile and León is divided into nine provinces: [citation needed]

Each of these provinces is named after its respective provincial capital.

Autonomous Executive

The executive of Castile and León is known as the Junta de Castilla y León in Spanish. [citation needed]

| Political party | Autonomic elections, 2011[33] | Autonomic elections, 2007[34] | Autonomic elections, 2003 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | Seats | Percentage | Seats | Percentage | Seats | |

| Partido Popular de Castilla y León | 51.59% | 53 | 49.41% | 48 | 48.56% | 48 |

| Partido Socialista de Castilla y León | 29.61% | 29 | 37.49% | 33 | 36.74% | 32 |

| Unión del Pueblo Leonés | 1.85% | 1 | 2.74% | 2 | 3.88% | 3 |

| Izquierda Unida LVCyL | 4.89% | 1 | 3.09% | 0 | 3.43% | 0 |

| Tierra Comunera - ACAL | - | - | 1.16% | 0 | 1.19% | 0 |

Culture

Languages

Besides the dominant Castilian Spanish, three other regional languages figure in the linguistic patrimony of Castile and León. Two of these are recognized explicitly in the Statute of Autonomy. The Leonese language, according to the Statute, "will be the object of specific protection [...] for its particular value in the linguistic heritage of the Community".[35] The Galician language, according to the statute, "merits respect and protection in the places where it is habitually used,[36] which is effectively to say the portions of the comarcas of El Bierzo and Sanabria bordering Galicia.

Education

- Universities

- Public

- Private

- Catholic University of Ávila (Universidad Católica Santa Teresa de Jesús de Ávila)

- Miguel de Cervantes European University (Valladolid)

- IE University (Instituto de Empresa Universidad, Segovia)

- Pontifical University of Salamanca

Demography

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 2,302,417 | — |

| 1910 | 2,362,878 | +2.6% |

| 1920 | 2,337,405 | −1.1% |

| 1930 | 2,477,324 | +6.0% |

| 1940 | 2,694,347 | +8.8% |

| 1950 | 2,864,378 | +6.3% |

| 1960 | 2,848,352 | −0.6% |

| 1970 | 2,623,196 | −7.9% |

| 1981 | 2,575,064 | −1.8% |

| 1991 | 2,562,979 | −0.5% |

| 2001 | 2,456,474 | −4.2% |

| 2011 | 2,540,188 | +3.4% |

| 2017 | 2,436,850 | −4.1% |

| Source: INE | ||

The most recent official census by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística, as January 1, 2011, gave a population of 2,540,188 (1,259,641 males and 1,280,546 females) representing 5.42 percent of the population of Spain. As of January 2011 the population of Castile and León, by province, stood as follows: Ávila, 171,647 inhabitants; Burgos, 372,538; León, 493,312; Palencia,170,513; Salamanca, 350,018; Segovia, 163,171; Soria, 94,610; Valladolid, 532,765; and Zamora, 191,613.[37]

Present-day population distribution

In 1960 only 20.6 percent of the population of present-day Castile and León was urban; by 1991 that percentage had risen to 42.3 percent. The decline in rural population has apparently been somewhat stemmed, with a 1998 statistic showing 43 percent.[citation needed]

Many rural areas became very sparsely populated in the mid-to-late 20th century. In 1986 there were seven times as many municipalities with less than 100 inhabitants as in 1960.

A recent study from University of Porto (Portugal) highlighted Castile and León - particularly the province of Salamanca - as one of the European regions where old people could expect to live longer.[38]

Notable cities include the nine provincial capitals plus Miranda de Ebro and Aranda de Duero in the province of Burgos, Ponferrada and San Andrés del Rabanedo in León, Béjar in Salamanca, and Medina del Campo and Laguna de Duero in Valladolid.

Of the 2,247 municipalities in the autonomous community, the 2000 census shows 1,970 with 1,000 or fewer inhabitants; 234 between 1,001 and 5,000; 20 between 5,001 and 10,000; 10 between 10,001 and 20,000; 6 between 20,001 and 50,000; 3 between 50,001 and 100,000; and 4 with over 100,000 inhabitants. Those last are Valladolid (319,943 in 2007), Burgos (174,075), Salamanca (159,754) and León (135,059). At the other extreme Blasconuño de Matacabras (Ávila) has a population of 18, Reinoso (Burgos) has 24, Villarmentero de Campos (Palencia), has 14, and Gormaz (Soria), 17.

| City | Population | City | Population | City | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valladolid | 313,437 | Ponferrada | 68,508 | Miranda de Ebro | 38,930 | ||

| Burgos | 179,251 | Zamora | 65,525 | Aranda de Duero | 33,229 | ||

| Salamanca | 153,472 | Ávila | 59,008 | San Andrés del Rabanedo | 31,562 | ||

| León | 132,744 | Segovia | 55,220 | Laguna de Duero | 22,334 | ||

| Palencia | 81,552 | Soria | 39,987 | Medina del Campo | 21,607 |

Economy

Castile and León accounts for 5.2% of Spain's GDP.[39]

Work force

In 2001 the work force was 1,005,200 with 884,200 employed, meaning 12.1 percent of the work force were out of work. 10.9 percent of the employed population work in agriculture, 20.6 percent in industry, 12.7 percent in construction, and 63.1 percent in the service sector.

In 2007, the unemployment rate was down to 6.99 percent,[40] but the late-2000s recession drove that number up to 14.14 percent by July 2009.[41]

Primary sector

The region has nine DO wine zones, which are mostly located around the Duero valley.[42]

Some 92,600 people work in the primary sector in Castile and León, about 10 percent of employment in the region. 2001 data showed 5 percent unemployment in this sector.[citation needed]

Broken down by provinces, approximately 9,400 are employed in this sector in Ávila, 8,100 each in Burgos and Palencia, 18,300 in León, 9,200 in Salamanca, 6,400 in Segovia, 5,600 in Soria, 8,300 in Valladolid, and 14,600 in Zamora. The region's agricultural and farming sector represent 7.6% of the total in Spain.[citation needed]

Secondary sector

As of 2000, industry 18 %of the work force were engaged in industry, generating 25 percent of regional GDP. The principal industrial centres are the cities of Valladolid (21,054 workers in industry), Burgos (20,217), Aranda de Duero (4,872), León (4,521) and Ponferrada (4,270).[43]

Tourism

Tourism highlights of the region include:[44]

- Burgos Cathedral

- León Cathedral

- Zamora Cathedral

- Segovia, with its fortress

- The walls of Ávila

- City of Salamanca

- Romanic churches of Zamora

Transportation

Rail

Castilla y León has an extensive rail network, including the principal lines from Madrid to Cantabria and Galicia. The line from Paris to Lisbon crosses the region, reaching the Portuguese frontier at Fuentes de Oñoro in Salamanca. Astorga, Burgos, León, Miranda de Ebro, Palencia, Ponferrada, Medina del Campo and Valladolid are all important railway junctions.[citation needed]

Railways operate in several different gauges: Iberian gauge (1,668 mm (5 ft 5+21⁄32 in)), UIC gauge (1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in)) and Narrow gauge (1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in)). Except for some narrow-gauge lines, trains are operated by RENFE on lines maintained by the Administrador de Infraestructuras Ferroviarias (ADIF); both of these are national, state-owned companies. [citation needed]

Iberian gauge lines (ADIF/RENFE)

- Madrid - Irun

- Madrid - Burgos

- Castejón de Ebro - Bilbao

- Venta de Baños - A Coruña

- Palencia - Santander

- León - Gijón

- Medina del Campo - Santiago de Compostela

- Medina del Campo - Fuentes de Oñoro

- Torralba - Soria

- Villalba - Segovia

Narrow gauge

- León - Bilbao: Ferrocarril de La Robla, Europe's longest narrow-gauge line, operated by FEVE

- Cercedilla - Cotos: operated by RENFE

- Ponferrada - Villablino: operated by the Ferrocarril MSP under the Junta of Castile and León

Roads

The region is also crossed by two major ancient routes:[citation needed]

- The Way of St. James, mentioned above as a World Heritage Site, now a hiking trail and a motorway, from east to west.

- The Roman Via de la Plata ("Silver Way"), mentioned above in the context of mining, now a main road through the west of the region.

The road network is regulated by the Ley de carreteras 10/2008 de Castilla y León (Highway Law 10/2008 of Castile and León).[45] This law allows for the possibility of roads financed by the private sector through concessions, as well as the public construction of roads that has long prevailed. [citation needed]

See also

Notes

- ^ "El PP renuncia a solicitar la capitalidad para evitar conflictos entre provincias" (in Spanish). El Mundo. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ Article 1 of the Project of Federal Constitution of the First Spanish Republic, July 17, 1873.

- ^ Investigaciones históricas. Valladolid. Secretariado de Publicaciones, Universidad de Valladolid, 1979.

- ^ a b Juan-Miguel Álvarez Domínguez.The Regionalist Catechism of Don Eugenio, an example of Castilian-Leonese regionalism sponsored by León. 1931, Argutorio, No. 19 (2nd semester 2007), pp. 32-36.

- ^ Diario de León (newspaper), May 22, 1936.

- ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

Statutewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ {{web cite | author = Fundación Las Edades del Hombre | title = Objectivos - Fundación Las Edades del Hombre. | url = http://www.lasedades.es/contentobjetivos.htm | urlarchive = https://web.archive.org/web/20110720003124/http://www.lasedades.es/contentobjetivos.htm | datearchive = 20 of julio of 2011 }}

- ^ {{web cite | title = Vive Tosacana | url = http://www.vivetoscana.com.ar/patrimonio-de-la-humanidad-de-la-unesco-en-toscana/ }}

- ^ {{web cite | author = Unesco: World Heritage Conservation | title = Italy | url = http://whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/it | language = English }}

- ^ "Europe & North America (289 biosphere reserves in 34 countries)". Unesco. June 2014.

- ^ María R. Mayor (June 19, 2013), "Unesco recognizes León as the worldwide cradle of parliamentarism", El Mundo (newspaper)

- ^ {{web cite | author = UNESCO: Memory of the World Programme | title = Memory of the World Programme - Spain | url = http://www.unesco.org/new/es/communication-and-information/flagship-project-activities/memory-of-the-world/register/access-by-region-and-country/europe-and-north-america/spain/ }}

- ^ {{cite | url = http://www.directoressociales.com/images/Dec2015/Folleto%20Indice%20DEC%202015.pdf | title = Índice de desarrollo de los servicios sociales 2015 | publisher = Asociación Estatal de Directores y Gerentes en Servicios Sociales | year = 2016 }}

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

PISA 2015was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cortes Generales (1995), "Organic Law 10/1995, of November 23 , of the Penal Code" (PDF), Boletín Oficial del Estado no. 281, of November 24, 1995, Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado

- ^ The Decreta of León of 1188 - The oldest documentary manifestation of the European parliamentary system

- ^ http://www.elnortedecastilla.es/leon/201408/13/santo-grial-eleva-visitas-20140813125836.html

- ^ http://www.abc.es/local-castilla-leon/20140326/abci-historiadores-concluyen-santo-grial-201403261750.html

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

CGCYLwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

Repúblicawas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cite error: The named reference

His researcheswas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Alejandro De Haro Honrubia. "La propuesta autonomista de Ortega y Gasset: un claro antecedente de la configuración autonómica del Estado español de 1978" (PDF). University of Castilla-La Mancha.

- ^ El País (newspaper). "Seis grupos políticos se fusionan en un partido regionalista en Castilla y León".

- ^ Diario de León (newspaper), May 5, 1984.

- ^ Diario de León, March 13, 2004.

- ^ "Fundación Villalar Castilla y León".

- ^ Castile and León Regional Government. "Premios Castilla y León".

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|datearchive=ignored (help); Unknown parameter|urlarchive=ignored (help) - ^ Template:Grupo Espeleologico Edelweiss 2010

- ^ http://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2010/06/04/castillayleon/1275667194.html

- ^ Bulletin of the AGE. "Riesgos climáticos en Castilla y León. Análisis de su peligrosidad" (PDF).

- ^ http://www.divulgameteo.es/fotos/meteoroteca/Monta%C3%B1as-clima-LGP.pdf

- ^ AEMET. "Atlas climático ibérico" (PDF).

- ^ Elecciones Municipales 2011 (El País).

- ^ Resultados autonómicos de Castilla y León Archived August 18, 2007, at archive.today (Cinco Días).

- ^ "será objeto de protección específica [...] por su particular valor dentro del patrimonio lingüístico de la Comunidad"

- ^ "gozará de respeto y protección en los lugares en que habitualmente se utilice"

- ^ National Statistics Institute

- ^ Ribeiro, Ana Isabel; Krainski, Elias Teixeira; Carvalho, Marilia Sá; Pina, Maria de Fátima de (2016-02-15). "Where do people live longer and shorter lives? An ecological study of old-age survival across 4404 small areas from 18 European countries". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 70: jech–2015-206827. doi:10.1136/jech-2015-206827. ISSN 1470-2738. PMID 26880296.

- ^ "Castilla y Leon". Internal Market, Industry. European Commission. Retrieved 10 December 2015. (login required)

- ^ El paro bajó en Castilla y León un 5% frente a un incremento nacional del 6,5, El Mundo, 2008-01-26. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ^ El paro sube en la Comunidad en 5.000 personas en el segundo trimestre, rtvcyl.es, 2009-07-24. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ^ "Castilla y Leon wines". Wine-Searcher. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ Fichas Municipales - 2008 DATOS ECONÓMICOS Y SOCIALES, Caja España, 2008. Archived December 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Introducing Castilla y León". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Ha entrado en vigor la nueva Ley de carreteras de Castilla y León que regula la planificación, proyección, construcción, conservación, financiación, uso y explotación de las carreteras con itinerario comprendido íntegramente en el territorio de la Comunidad Autónoma de Castilla y León y que no sean de titularidad del Estado. [1][dead link]