Castile and León: Difference between revisions

ILoveCaracas (talk | contribs) |

ILoveCaracas (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

||

| Line 111: | Line 111: | ||

Following the same wording, the banner is constituted by the shield quartered on a traditional [[crimson]] background. The Statute also expresses: "The anthem and the other symbols [...] will be regulated by specific law". After the promulgation of the fundamental norm, this law was not promulgated, so the anthem does not exist, but ''de iure'' is a symbol of autonomy.<ref name = "Statute"/> |

Following the same wording, the banner is constituted by the shield quartered on a traditional [[crimson]] background. The Statute also expresses: "The anthem and the other symbols [...] will be regulated by specific law". After the promulgation of the fundamental norm, this law was not promulgated, so the anthem does not exist, but ''de iure'' is a symbol of autonomy.<ref name = "Statute"/> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:IglesiaDeSanPablo20110905170422P1120849.jpg|thumb|left|[[Iglesia de San Pablo, Valladolid|Conventual Church of San Pablo]] and [[Colegio de San Gregorio]], where the [[Valladolid debate]] was held, origin of the first theses of [[human rights]] ([[Laws of Burgos]]) and [[Palacio de Pimentel|Palace of Pimentel]], place of birth of the king [[Philip II of Spain]].]] |

|||

The autonomous community of Castile and León is the result of the union in 1983 of nine provinces: the three that, after the territorial division of 1833, by which the provinces were created, were ascribed to the [[León (historical region)|Region of León]] and six attached to the [[Old Castile]], except in the latter case the provinces of [[Province of Santander (Spain)|Santander]] (current community of [[Cantabria]]) and [[province of Logroño|Logroño]] (current [[La Rioja (Spain)|La Rioja]]). |

|||

In the case of [[Cantabria]] the creation of an [[autonomous community]] was advocated for historical, cultural and geographic reasons, while in [[La Rioja (Spain)|La Rioja]] the process was more complex due to the existence of three routes, all based on historical and socio-economic reasons: union with Castile and León ([[Union of the Democratic Centre (Spain)|Union of the Democratic Centre]]), union to a Basque-Navarrese community ([[Spanish Socialist Workers' Party|Socialist Party]] and [[Communist Party of Spain|Communist Party]]) or creation of an uniprovincial autonomy, option taken before the majority support of its population. |

|||

[[File:Homo heildebergensis. Museo de Prehistoria de Valencia.jpg|thumb|upright|[[Miguelón|Skull number 5]] of ''[[Homo heidelbergensis]]'', as it appeared in the 1992 campaign, extracted from the [[Atapuerca Mountains]].]] |

|||

Several are the archaeological findings that show that in prehistoric times these lands were already inhabited. In the [[Atapuerca Mountains]] have been found many bones of the ancestors of ''Homo sapiens'', making these findings one of the most important to determine the history of human evolution. The most important discovery that catapulted the site to international fame was the remains of ''[[Homo heidelbergensis]]''. |

|||

Before the arrival of the Romans, it is known that the territories that make up Castile and León today were occupied by various [[Celts|Celtic peoples]], such as [[vaccaei]], [[autrigones]], [[turmodigi]], the [[vettones]], [[astures]] or [[celtiberians]]. |

|||

With the arrival of the Roman troops, confrontations took place between the pre-Roman peoples and these. In the history remains the resistance of [[Numantia]], near the current [[Soria]]. |

|||

The [[Romanization (cultural)|romanization]] was unstoppable, and to this day great Roman works of art have remained, mainly the [[Aqueduct of Segovia]] as well as many archaeological remains such as those of the ancient [[Clunia]] , [[Salt mines of Poza de la Sal]] and [[vía de la Plata]], originating in [[Astorga, Spain|Astorga]] (''[[Asturica Augusta]]'') and that crosses the west of the community to the capital of [[Extremadura]], [[Mérida, Spain|Mérida]] (''[[Emerita Augusta]]''). |

|||

[[File:Toros de Guisando.jpg|thumb|left|[[Bulls of Guisando]], in [[El Tiemblo]], [[Ávila]]. These [[verraco]]s, of [[Celtic]] origin, are found in many towns in the western Castile and León.]] |

|||

With the fall of Rome, the lands were occupied militarily by the [[Visigoths|Visigoth]] peoples. The subsequent arrival of the Muslims and the subsequent reconquista have a lot to do with the current ethnic composition of the Iberian Peninsula. In the mountainous area of the current [[Asturias]] a small Christian kingdom was formed that opposed the Islamic presence in the Peninsula. They proclaimed themselves heirs of the last Visigoth kings, who in turn had been deeply romanized. This resistance of Visigoth-Roman heritage and supported by Christianity, was becoming increasingly strong and expanding to the south, passing its capital to the city of [[León, Spain|León]] and thus creating the [[Kingdom of León]]. To favor the repopulation of the new reconquered lands, were granted by the monarchs [[fuero]]s or letters of repopulation. |

|||

[[File:Castro de Ulaca 10 by-dpc.jpg|thumb|right|Celtiberian [[castro of Ulaca]].]] |

|||

In the [[Middle Ages]] the pilgrimage by Christianity to [[Santiago de Compostela]] was popularized. The [[Camino de Santiago]] runs throughout the region, which contributed to European culture traveling and expanding throughout the peninsula. Today that Camino is still a tourist and cultural claim of the first order. |

|||

In 1188 the [[Basílica de San Isidoro, León|basilica of San Isidoro of León]] had been the seat of the first [[Cortes of León|parliamentary body]] of the history of Western Europe in 1188 with the participation of [[Estates_of_the_realm#Third_Estate|Third Estate]]. The king who summoned them was [[Alfonso IX of León]]. |

|||

The legal basis was the [[Roman law]], due to which the kings increasingly wanted more power, like the Roman emperors. This fact is very clearly seen in the ''[[Siete Partidas]]'' of [[Alfonso X of Castile]], which makes clear the imperial monism that he sought. The King did not want to be a ''[[primus inter pares]]'', the king was the source of the law. |

|||

[[File:AcueductoSegovia04.JPG|thumb|left|[[Aqueduct of Segovia]], [[Ancient Rome|Roman]] construction.]] |

|||

Simultaneously, a county of this Christian kingdom of León, begins to acquire autonomy and to expand. This is the primitive [[County of Castile]], which will grow into a real kingdom of great strength among the Christian kingdoms of the Peninsula. The first Castilian count was [[Fernán González of Castile|Fernán González]]. |

|||

[[File:Cronica del muy esforçado cauallero el Cid ruy diaz campeador.gif|thumb|upright|[[El Cid]] knight.]] |

|||

León and Castile continued to expand to the South, even beyond the [[Douro]] with its purpose of struggle and reconquest against Islam. We are in the middle of the Middle Ages and the songs of deed tell of the great deeds of the Christian nobles who fought against the Muslim enemy. Despite this, Christian and Muslim kings maintained diplomatic relations. Clear example is [[El Cid|Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, ''El Cid'']], paradigm of the medieval Christian knight, who fought both hand of Christian kings and Muslims. |

|||

The bases of the dynastic unification of the kingdoms of Castile and León, separated by only seven decades, had been put in 1194. [[Alfonso VIII of Castile]] and [[Alfonso IX of León]] signed in [[Tordehumos]] the treaty that pacified the area of [[Tierra de Campos]] and laid the foundations for a future reunification of the kingdoms, consolidated in 1230 with [[Ferdinand III of Castile|Ferdinand III ''the Saint'']]. This agreement has gone down in history as the ''[[Treaty of Tordehumos]]''. |

|||

[[File:PanteónSanIsidoroLeón.jpg|thumb|[[Pantheon of kings of the Basílica de San Isidoro of León|Pantheon of kings]] of the [[Basílica de San Isidoro, León|Basilica of San Isidoro of León]]. [[Alfonso IX of León|Alfonso IX]] convened the [[Cortes of León|Cortes of León of 1188]], first parliamentary body of the history of Western Europe with presence of [[Estates_of_the_realm#Third_Estate|Third Estate]]. In the same [[Basílica de San Isidoro, León|basilica]] is the [[Chalice of Doña Urraca]], which some researchers assimilate with the [[Holy Grail]].<ref>http://www.elnortedecastilla.es/leon/201408/13/santo-grial-eleva-visitas-20140813125836.html</ref><ref>http://www.abc.es/local-castilla-leon/20140326/abci-historiadores-concluyen-santo-grial-201403261750.html</ref>]] |

|||

With Ferdinand III, Castile and León are united under the same kingdom in a definitive way and to this day, and before him the kingdoms had already remained under the same command for some seasons. |

|||

During the [[Late Middle Ages]] there was an economic and political crisis produced by a series of bad harvests and by disputes between nobles and the Crown for power, as well as between different contenders for the throne. In the [[Cortes of Valladolid (1295)|Cortes of Valladolid of 1295]], [[Ferdinand IV of Castile|Ferdinand IV]] is recognized as king. The painting [[María de Molina presents her son Fernando IV in the Cortes of Valladolid of 1295]] presides today the Congress of Deputies along with a painting of the Cortes of Cádiz, emphasizing the parliamentarian importance that has all the development of Cortes in Castile and León, despite its subsequent decline. The Crown was becoming more authoritarian and the nobility more dependent on it. |

|||

The [[reconquista]] continued advancing in this thriving [[Crown of Castile]], and culminated with the surrender of the [[Emirate of Granada|Nasrid Kingdom of Granada]], last Muslim stronghold in the Peninsula. |

|||

The [[Catholic Monarchs]] shared the maritime routes and the New World with the Portuguese crown in the [[Treaty of Tordesillas]]. |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Spain has alternated between regionalism and centralization several times in the last century and a half. In 1869, the republicans of the present Castile and León plus the provinces of Santander (now [[Cantabria]]) and Logroño (now [[La Rioja (Spain)|La Rioja]]) had drafted the [[Castilian Federal Pact]] (''Pacto Federal Castellano''), which projected the creation of a federated state under the name ''Castilla la Vieja'' (Old Castile) in these eleven provinces. During the [[First Spanish Republic|First Republic]] (1873–1874), the [[Republican Democratic Federal Party]] (''Partido Republicano Democrático Federal'') intended to make this a reality.<ref>Artículo 1, ''Proyecto Constitución Federal de la I República Española'', 17 de julio de 1873</ref> However, the fall of the Republic at the beginning of 1874 put an end to this initiative.<ref>''Investigaciones históricas''. Valladolid: Secretariado de Publicaciones, Universidad de Valladolid, 1979</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | In 1921, on the fourth centenary of the Battle of Villalar, the municipal government of [[Santander, Cantabria]] advocated for the establishment of a Castilian commonwealth of these same eleven provinces. In late 1931 and early 1932, the priest [[Eugenio Merino]], in León, wrote a piece for the ''[[Diario de León]]'' stating a basis for Castilian-Leonese regionalism.<ref>Juan-Miguel Alvarez Dominguez, "[http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/fichero_articulo?codigo=2381262&orden=0 El Catecismo Regionalista de Don Eugenio, un ejemplo de regionalismo castellanoleonés patrocinado desde León (1931)]", ''Argutorio'', nº 19 (2º semestre 2007), pp. 32-36.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | During the [[Second Spanish Republic|Second Republic]], especially in 1936, there was a great deal of regionalist activity favorable to a region of eleven provinces, including the elaboration of the basis of a statute of autonomy. The ''Diario de León'' advocated for the formalization of this initiative and the constitution of an autonomous region as follows: "to unite in one personality León and Old Castile around the great basin of the Douro, without falling now into simple village rivalries."<ref>«''unir en una personalidad a León y [[Castilla la Vieja]] en torno a la gran cuenca del Duero, sin caer ahora en rivalidades pueblerinas''». ''Diario de León'', 22 de mayo de 1936.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | After the death of the dictator [[Francisco Franco]] unleashed the [[Spanish transition to democracy]], there was an upwelling of Castilian-Leonese regionalist, autonomist and nationalist organizations, such as [[Alianza Regional de Castilla y León]] (1975), [[Instituto Regional de Castilla y León]] (1976) and the Autonomic Nationalist Party of Castile and León (Partido Autonómico Nacionalista de Castilla y León, [[PANCAL]], 1977). None of these survive today, but similar sentiments are now represented by [[Unidad Regionalista de Castilla y León]] (1993).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.elpais.com/articulo/espana/ESPANA/CASTILLA_Y_LEON/UNIDAD_REGIONALISTA_DE_CASTILLA_Y_LEON/PARTIDO_NACIONALISTA_DE_CASTILLA_Y_LEON/grupos/politicos/fusionan/partido/regionalista/Castilla/Leon/elpepiesp/19920427elpepinac_6/Tes |title=Seis grupos políticos se fusionan en un partido regionalista en Castilla y León |publisher=Elpais.com |date= |accessdate=2010-10-03}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The Provincial Deputation of León agreed on April 16, 1980 to endorse the Castilian-Leonese process, but then revoked that support January 13, 1983, just as the proposed [[Organic Law (Spain)|Organic Law]] was before the Spanish parliament. The [[Constitutional Court of Spain]] upheld the first of these two contradictory Leonese resolutions.<ref>Tribunal Constitucional Española, Sentencia 89/1984, fundamento de derecho 5, September 28, 1984.</ref> The court's decision was met by demonstrations in León and elsewhere in the Leonese territories in favor of a policy of ''León solo'' ("León alone"). The roughly 90,000 people who gathered in León at that time<ref>''Diario de León'', 5 de mayo de 1984.</ref> constituted the largest demonstration in that city between the revival of democracy and the demonstrations after the [[2004 Madrid train bombings]].<ref>''Diario de León'', 13 de marzo de 2004.</ref> |

||

== Geography == |

== Geography == |

||

| Line 231: | Line 283: | ||

** [[Pontifical University of Salamanca]] |

** [[Pontifical University of Salamanca]] |

||

| ⚫ | |||

[[File:IMG Toros de Guisando.JPG|thumb|left|There are [[Verraco]]s, megalithic monuments, around all Western Castile and León.]] |

|||

[[File:AcueductoSegovia edit1.jpg|thumb|The [[Roman empire|Roman]] [[Aqueduct of Segovia]]]] |

|||

[[File:Ávila 24-8-2002.jpg|thumb|left|Medieval Walls of [[Ávila, Spain|Ávila]].]] |

|||

[[File:PanteónSanIsidoroLeón.jpg|thumb|[[Basilica of San Isidoro]] in [[Province of León|León]], where in 1188 were celebrated the first [[León's Spanish Parliament|parliament season]] of the history of [[Europe]].]] |

|||

[[File:Fachada de la iglesia conventual de San Pablo (Valladolid).jpg|thumb|Façade of [[Iglesia de San Pablo, Valladolid|San Pablo Church]] in [[Valladolid]].]] |

|||

[[File:Panorámica Catedral de Burgos.jpg|thumb|left|[[Burgos Cathedral]], burial place of [[El Cid]]]] |

|||

[[File:Episcopal Palace of Astorga.jpg|thumb|right|Episcopal Palace of [[Astorga, Spain|Astorga]], museum in the [[Way of St. James]].]] |

|||

[[File:Catedral Zamora03.JPG|thumb|left|The dome of the [[cathedral of Zamora]].]] |

|||

Castile and León traces its history to the medieval kingdoms of [[Kingdom of Castile|Castile]] and [[Kingdom of León|León]], which were permanently united under the [[Crown of Castile]] in 1301. Together with other Christian-ruled [[Iberian peninsula|Iberian]] kingdoms, the separate monarchies of Castile and León participated in the ''[[Reconquista]]'', the re-conquest of Iberia from the [[Moors]], its medieval [[Muslim]] rulers. {{citation needed|date=March 2015}} |

|||

The first [[dynastic union]] of León and Castile came about in 1037, when [[Ferdinand I of Castile|Ferdinand]], the 20-year-old Count of Castile, defeated his brother-in-law [[Bermudo III of León]] in battle and claimed the Crown of León through the rights of his own wife, [[Sancha of León|Sancha]], Bermudo's sister. {{citation needed|date=March 2015}} |

|||

The medieval Cortes of León is one of the earliest ancestors of Europe's [[parliament]]s. The remote origins of the Cortes dates back to the early 12th century. The [[:es:Cortes de León de 1188|Cortes of León of 1188]] called by Alfonso IX is one of the earliest documented gatherings of the [[estates of the realm|estates]] in which commoners of the cities and towns are represented beside the clergy and nobility as counselors to the monarch. Alfonso gathered similar assemblies in 1202 in Benavente and 1208 in León. {{citation needed|date=March 2015}} |

|||

Valladolid was home to a number of Castilian kings between the 12th and 17th centuries.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.insightguides.com/destinations/europe/spain/castilla-y-leon/overview|title=Castilla y Leon travel guide|work=Insight Guides|publisher=Apa Publications|accessdate=6 March 2015}}</ref> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | Spain has alternated between regionalism and centralization several times in the last century and a half. In 1869, the republicans of the present Castile and León plus the provinces of Santander (now [[Cantabria]]) and Logroño (now [[La Rioja (Spain)|La Rioja]]) had drafted the [[Castilian Federal Pact]] (''Pacto Federal Castellano''), which projected the creation of a federated state under the name ''Castilla la Vieja'' (Old Castile) in these eleven provinces. During the [[First Spanish Republic|First Republic]] (1873–1874), the [[Republican Democratic Federal Party]] (''Partido Republicano Democrático Federal'') intended to make this a reality.<ref>Artículo 1, ''Proyecto Constitución Federal de la I República Española'', 17 de julio de 1873</ref> However, the fall of the Republic at the beginning of 1874 put an end to this initiative.<ref>''Investigaciones históricas''. Valladolid: Secretariado de Publicaciones, Universidad de Valladolid, 1979</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | In 1921, on the fourth centenary of the Battle of Villalar, the municipal government of [[Santander, Cantabria]] advocated for the establishment of a Castilian commonwealth of these same eleven provinces. In late 1931 and early 1932, the priest [[Eugenio Merino]], in León, wrote a piece for the ''[[Diario de León]]'' stating a basis for Castilian-Leonese regionalism.<ref>Juan-Miguel Alvarez Dominguez, "[http://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/fichero_articulo?codigo=2381262&orden=0 El Catecismo Regionalista de Don Eugenio, un ejemplo de regionalismo castellanoleonés patrocinado desde León (1931)]", ''Argutorio'', nº 19 (2º semestre 2007), pp. 32-36.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | During the [[Second Spanish Republic|Second Republic]], especially in 1936, there was a great deal of regionalist activity favorable to a region of eleven provinces, including the elaboration of the basis of a statute of autonomy. The ''Diario de León'' advocated for the formalization of this initiative and the constitution of an autonomous region as follows: "to unite in one personality León and Old Castile around the great basin of the Douro, without falling now into simple village rivalries."<ref>«''unir en una personalidad a León y [[Castilla la Vieja]] en torno a la gran cuenca del Duero, sin caer ahora en rivalidades pueblerinas''». ''Diario de León'', 22 de mayo de 1936.</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | After the death of the dictator [[Francisco Franco]] unleashed the [[Spanish transition to democracy]], there was an upwelling of Castilian-Leonese regionalist, autonomist and nationalist organizations, such as [[Alianza Regional de Castilla y León]] (1975), [[Instituto Regional de Castilla y León]] (1976) and the Autonomic Nationalist Party of Castile and León (Partido Autonómico Nacionalista de Castilla y León, [[PANCAL]], 1977). None of these survive today, but similar sentiments are now represented by [[Unidad Regionalista de Castilla y León]] (1993).<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.elpais.com/articulo/espana/ESPANA/CASTILLA_Y_LEON/UNIDAD_REGIONALISTA_DE_CASTILLA_Y_LEON/PARTIDO_NACIONALISTA_DE_CASTILLA_Y_LEON/grupos/politicos/fusionan/partido/regionalista/Castilla/Leon/elpepiesp/19920427elpepinac_6/Tes |title=Seis grupos políticos se fusionan en un partido regionalista en Castilla y León |publisher=Elpais.com |date= |accessdate=2010-10-03}}</ref> |

||

| ⚫ | |||

| ⚫ | The Provincial Deputation of León agreed on April 16, 1980 to endorse the Castilian-Leonese process, but then revoked that support January 13, 1983, just as the proposed [[Organic Law (Spain)|Organic Law]] was before the Spanish parliament. The [[Constitutional Court of Spain]] upheld the first of these two contradictory Leonese resolutions.<ref>Tribunal Constitucional Española, Sentencia 89/1984, fundamento de derecho 5, September 28, 1984.</ref> The court's decision was met by demonstrations in León and elsewhere in the Leonese territories in favor of a policy of ''León solo'' ("León alone"). The roughly 90,000 people who gathered in León at that time<ref>''Diario de León'', 5 de mayo de 1984.</ref> constituted the largest demonstration in that city between the revival of democracy and the demonstrations after the [[2004 Madrid train bombings]].<ref>''Diario de León'', 13 de marzo de 2004.</ref> |

||

== Demography == |

== Demography == |

||

Revision as of 02:41, 4 January 2018

Castile and León

[Castilla y León] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) Template:Es icon Castiella y Llión (in Leonese) [Castela e León] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) Template:Link language | |

|---|---|

| [Castilla y León] Error: {{Lang}}: text has italic markup (help) Template:Es icon | |

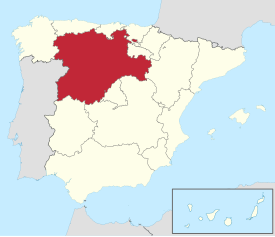

Location of Castile and León within Spain | |

| Coordinates: 41°23′N 4°27′W / 41.383°N 4.450°W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Capital | Undeclared (Valladolid de facto[1]) |

| Government | |

| • President | Juan Vicente Herrera (PP) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 94,222 km2 (36,379 sq mi) |

| • Rank | 1st (18.6% of Spain) |

| Population (2016) | |

| • Total | 2,447,519 |

| • Density | 26/km2 (67/sq mi) |

| • Pop. rank | 6th |

| • Percent | 5.42% of Spain |

| Demonym | |

| ISO 3166-2 | CL |

| Official languages | Spanish (Leonese and Galician have special status) |

| Statute of Autonomy | 2 March 1983 |

| Parliament | Cortes of Castile and León |

| Congress seats | 31 (of 350) |

| Senate seats | 39 (of 266) |

| Website | Junta de Castilla y León |

Castile and León (/kæˈstiːl ... liˈɒn/; Spanish: Castilla y León [kasˈtiʎa i leˈon] ; Leonese: Castiella y Llión [kasˈtjeʎa i ʎiˈoŋ]; Galician: Castela e León [kasˈtɛla e leˈoŋ]) is an autonomous community in north-western Spain. It was constituted in 1983, although it existed for the first time during the First Spanish Republic in the 19th century. León first appeared as a Kingdom in 910, whilst the Kingdom of Castile gained an independent identity in 1065 and was intermittently held in personal union with León before merging with it permanently in 1230. It is the largest autonomous community in Spain and the third largest region of the European Union, covering an area of 94,223 square kilometres (36,380 sq mi) with an official population of around 2.5 million (2011).

From the beginning of the federalist debate in Spain in the 19th century during the First Spanish Republic there were projects of autonomy for a Castile and León region, as the project of Castilian Mancomunity, Bases de Segovia, Castilian Provincial League or Castilian Federal Pact, but also including current Cantabria and La Rioja.[2][3] Same project that continued to exist during the Second Spanish Republic[4][5] and that was finally carried out after the Constitution of 1978 , but without Cantabria and La Rioja that, although it was considered to include them, finally formed uniprovincial autonomies.

Its Statute of Autonomy declares in its preamble:

The Autonomous Community of Castile and León arises from the modern union of the historical territories that composed and gave name to the old crowns of León and Castile. Eleven hundred years ago, the Kingdom of León was constituted, from which that of Castile and Galicia were dislodged as kingdoms throughout the 9th century, and, in 1143, that of Portugal. During these two centuries the monarchs who held the government of these lands attained the dignity of emperors, as attested by the terms of Alfonso VI and Alfonso VII.[6]

In Castile and León, more than 60% of all of Spain's heritage sites are found (architectural, artistic, cultural, etc.).[7] All of which translate into: 8 World Heritage sites, almost 1800 classified cultural heritage assets, 112 historic sites, 400 museums, more than 500 castles, of which 16 are considered of high historical value, 12 cathedrals, 1 concathedral, and the largest concentration of Romanesque art in the world. With 8 World Heritage sites, Castile and León is the region of the world with more cultural assets distinguished by the highest protection figure granted by Unesco, ahead of the Italian regions of Tuscany and Lombardy, both with 6 sites.[8] [9]

Also, the Montes de Valsaín mountains and the Béjar and Francia mountain ranges, in the Sistema Central, the valleys of Laciana, Omaña y Luna and the Picos de Europa and Los Ancares, in the Cantabrian Mountains, and the Iberian Plateau, in the border area with Portugal, have been declared biosphere reserve by UNESCO, which also recognizes the geopark of La Lora with this figure of protection.[10] In addition, Castile and León is strongly related to two of the records of the Memory of the World Programme of UNESCO which are the Decreta of the Cortes of León of 1188, curia regia considered the birthplace of worldwide parliamentarism by the institution itself,[11] and the Treaty of Tordesillas.[12]

The Index of development of social services reflects that the community has one of the best social services in the country, positioning itself as the third autonomy that offers the best benefits to its citizens, after the Basque Country and Navarre.[13] Its education, according to the Programme for International Student Assessment report of 2015, leads the scores in reading and sciences with a score comparable to that of the ten best countries in the study.[14]

23 April is designated Castile and León Day, commemorating the defeat of the comuneros at the Battle of Villalar during the Revolt of the Comuneros, in 1521. [citation needed]

Symbols

The Statute of Autonomy of Castile and León, reformed for the last time in 2007, establishes in the sixth article of its preliminary title the symbols of the community's exclusive identity. These are: the coat of arms, the flag, the banner and the anthem. Its legal protection is the same as that corresponding to the symbols of the State -whose outrages are classified as crime in article 543 of the Penal Code-.[6][15]

In the articulated statuary, the coat of arms is defined as follows:[6]

The coat of arms of Castile and León is a stamped shield by open royal crown, barracked in cross. The first and fourth quartering: in the field of gules, a merloned golden castle of three merlons, drafted of sable and rinse of azure. The second and third quartering: in a silver field, a rampant lion of purple, lingued, dyed and armed with gules, crowned with gold.

Likewise, the flag is described as follows:[6]

The flag of Castile and León is quartered and contains the symbols of Castile and León, as described in the previous section. The flag will fly in all the centres and official acts of the Community, to the right of the Spanish flag.

Following the same wording, the banner is constituted by the shield quartered on a traditional crimson background. The Statute also expresses: "The anthem and the other symbols [...] will be regulated by specific law". After the promulgation of the fundamental norm, this law was not promulgated, so the anthem does not exist, but de iure is a symbol of autonomy.[6]

History

The autonomous community of Castile and León is the result of the union in 1983 of nine provinces: the three that, after the territorial division of 1833, by which the provinces were created, were ascribed to the Region of León and six attached to the Old Castile, except in the latter case the provinces of Santander (current community of Cantabria) and Logroño (current La Rioja).

In the case of Cantabria the creation of an autonomous community was advocated for historical, cultural and geographic reasons, while in La Rioja the process was more complex due to the existence of three routes, all based on historical and socio-economic reasons: union with Castile and León (Union of the Democratic Centre), union to a Basque-Navarrese community (Socialist Party and Communist Party) or creation of an uniprovincial autonomy, option taken before the majority support of its population.

Several are the archaeological findings that show that in prehistoric times these lands were already inhabited. In the Atapuerca Mountains have been found many bones of the ancestors of Homo sapiens, making these findings one of the most important to determine the history of human evolution. The most important discovery that catapulted the site to international fame was the remains of Homo heidelbergensis.

Before the arrival of the Romans, it is known that the territories that make up Castile and León today were occupied by various Celtic peoples, such as vaccaei, autrigones, turmodigi, the vettones, astures or celtiberians.

With the arrival of the Roman troops, confrontations took place between the pre-Roman peoples and these. In the history remains the resistance of Numantia, near the current Soria.

The romanization was unstoppable, and to this day great Roman works of art have remained, mainly the Aqueduct of Segovia as well as many archaeological remains such as those of the ancient Clunia , Salt mines of Poza de la Sal and vía de la Plata, originating in Astorga (Asturica Augusta) and that crosses the west of the community to the capital of Extremadura, Mérida (Emerita Augusta).

With the fall of Rome, the lands were occupied militarily by the Visigoth peoples. The subsequent arrival of the Muslims and the subsequent reconquista have a lot to do with the current ethnic composition of the Iberian Peninsula. In the mountainous area of the current Asturias a small Christian kingdom was formed that opposed the Islamic presence in the Peninsula. They proclaimed themselves heirs of the last Visigoth kings, who in turn had been deeply romanized. This resistance of Visigoth-Roman heritage and supported by Christianity, was becoming increasingly strong and expanding to the south, passing its capital to the city of León and thus creating the Kingdom of León. To favor the repopulation of the new reconquered lands, were granted by the monarchs fueros or letters of repopulation.

In the Middle Ages the pilgrimage by Christianity to Santiago de Compostela was popularized. The Camino de Santiago runs throughout the region, which contributed to European culture traveling and expanding throughout the peninsula. Today that Camino is still a tourist and cultural claim of the first order.

In 1188 the basilica of San Isidoro of León had been the seat of the first parliamentary body of the history of Western Europe in 1188 with the participation of Third Estate. The king who summoned them was Alfonso IX of León.

The legal basis was the Roman law, due to which the kings increasingly wanted more power, like the Roman emperors. This fact is very clearly seen in the Siete Partidas of Alfonso X of Castile, which makes clear the imperial monism that he sought. The King did not want to be a primus inter pares, the king was the source of the law.

Simultaneously, a county of this Christian kingdom of León, begins to acquire autonomy and to expand. This is the primitive County of Castile, which will grow into a real kingdom of great strength among the Christian kingdoms of the Peninsula. The first Castilian count was Fernán González.

León and Castile continued to expand to the South, even beyond the Douro with its purpose of struggle and reconquest against Islam. We are in the middle of the Middle Ages and the songs of deed tell of the great deeds of the Christian nobles who fought against the Muslim enemy. Despite this, Christian and Muslim kings maintained diplomatic relations. Clear example is Rodrigo Díaz de Vivar, El Cid, paradigm of the medieval Christian knight, who fought both hand of Christian kings and Muslims.

The bases of the dynastic unification of the kingdoms of Castile and León, separated by only seven decades, had been put in 1194. Alfonso VIII of Castile and Alfonso IX of León signed in Tordehumos the treaty that pacified the area of Tierra de Campos and laid the foundations for a future reunification of the kingdoms, consolidated in 1230 with Ferdinand III the Saint. This agreement has gone down in history as the Treaty of Tordehumos.

With Ferdinand III, Castile and León are united under the same kingdom in a definitive way and to this day, and before him the kingdoms had already remained under the same command for some seasons.

During the Late Middle Ages there was an economic and political crisis produced by a series of bad harvests and by disputes between nobles and the Crown for power, as well as between different contenders for the throne. In the Cortes of Valladolid of 1295, Ferdinand IV is recognized as king. The painting María de Molina presents her son Fernando IV in the Cortes of Valladolid of 1295 presides today the Congress of Deputies along with a painting of the Cortes of Cádiz, emphasizing the parliamentarian importance that has all the development of Cortes in Castile and León, despite its subsequent decline. The Crown was becoming more authoritarian and the nobility more dependent on it.

The reconquista continued advancing in this thriving Crown of Castile, and culminated with the surrender of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada, last Muslim stronghold in the Peninsula.

The Catholic Monarchs shared the maritime routes and the New World with the Portuguese crown in the Treaty of Tordesillas.

Antecedents to the autonomous community

Spain has alternated between regionalism and centralization several times in the last century and a half. In 1869, the republicans of the present Castile and León plus the provinces of Santander (now Cantabria) and Logroño (now La Rioja) had drafted the Castilian Federal Pact (Pacto Federal Castellano), which projected the creation of a federated state under the name Castilla la Vieja (Old Castile) in these eleven provinces. During the First Republic (1873–1874), the Republican Democratic Federal Party (Partido Republicano Democrático Federal) intended to make this a reality.[18] However, the fall of the Republic at the beginning of 1874 put an end to this initiative.[19]

In 1921, on the fourth centenary of the Battle of Villalar, the municipal government of Santander, Cantabria advocated for the establishment of a Castilian commonwealth of these same eleven provinces. In late 1931 and early 1932, the priest Eugenio Merino, in León, wrote a piece for the Diario de León stating a basis for Castilian-Leonese regionalism.[20]

During the Second Republic, especially in 1936, there was a great deal of regionalist activity favorable to a region of eleven provinces, including the elaboration of the basis of a statute of autonomy. The Diario de León advocated for the formalization of this initiative and the constitution of an autonomous region as follows: "to unite in one personality León and Old Castile around the great basin of the Douro, without falling now into simple village rivalries."[21]

After the death of the dictator Francisco Franco unleashed the Spanish transition to democracy, there was an upwelling of Castilian-Leonese regionalist, autonomist and nationalist organizations, such as Alianza Regional de Castilla y León (1975), Instituto Regional de Castilla y León (1976) and the Autonomic Nationalist Party of Castile and León (Partido Autonómico Nacionalista de Castilla y León, PANCAL, 1977). None of these survive today, but similar sentiments are now represented by Unidad Regionalista de Castilla y León (1993).[22]

Forming the autonomous community

The Provincial Deputation of León agreed on April 16, 1980 to endorse the Castilian-Leonese process, but then revoked that support January 13, 1983, just as the proposed Organic Law was before the Spanish parliament. The Constitutional Court of Spain upheld the first of these two contradictory Leonese resolutions.[23] The court's decision was met by demonstrations in León and elsewhere in the Leonese territories in favor of a policy of León solo ("León alone"). The roughly 90,000 people who gathered in León at that time[24] constituted the largest demonstration in that city between the revival of democracy and the demonstrations after the 2004 Madrid train bombings.[25]

Geography

Castile and León is bordered by Portugal and Galicia to the west and by Asturias and Cantabria to the north. Aragon, the Basque Country and La Rioja is to the east and the border to the south is with Madrid, and with Castile-La Mancha and Extremadura to the southwest.

Castile and León is in the Meseta Central, a plateau in the middle of the northern half of the Iberian Peninsula; the Spanish part of the Douro River basin is nearly coterminous. There is also El Bierzo (León) and Laciana (León), Valle de Mena (Burgos), and the Valle del Tietar (Ávila), very secluded mountain valleys including some from neighbouring valleys and stretches. [citation needed]

Terrain

Much of its territory consists of a large, central plateau - the Meseta. Its height lies between 700-1000m.[26]

Rivers

The most prominent hydrographic feature of Castile and León is the River Douro (Spanish: Duero) and its tributaries. The Douro runs 897 kilometres (557 mi) from its headwaters in the Picos de Urbión in Soria to its mouth at the Portuguese city of Porto. Flowing into the Douro from the north, on its right bank, are the Pisuerga, the Valderaduey and the Esla, its most capacious tributaries, and from the east, on its left bank, the lesser flows of the Adaja and Duratón. [citation needed]

Climate

The highest rainfall is found in León, with a yearly average of 556mm, whilst Palencia has the lowest amount.[27] The region has a continental climate, characterized by relatively cold winters and dry warm summers. This is the result of distance from the sea and high altitude. Only two small areas have a milder climate, the section of the province of Avila which extends south of Gredos mountains into the Tiétar valley, and the area where the Duero river forms a natural border between Zamora province and Portugal known as the Arribes del Duero. [citation needed]

Regional administration and government

Castile and León is divided into nine provinces: [citation needed]

Each of these provinces is named after its respective provincial capital.

Autonomous Executive

The executive of Castile and León is known as the Junta de Castilla y León in Spanish. [citation needed]

| Political party | Autonomic elections, 2011[28] | Autonomic elections, 2007[29] | Autonomic elections, 2003 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | Seats | Percentage | Seats | Percentage | Seats | |

| Partido Popular de Castilla y León | 51.59% | 53 | 49.41% | 48 | 48.56% | 48 |

| Partido Socialista de Castilla y León | 29.61% | 29 | 37.49% | 33 | 36.74% | 32 |

| Unión del Pueblo Leonés | 1.85% | 1 | 2.74% | 2 | 3.88% | 3 |

| Izquierda Unida LVCyL | 4.89% | 1 | 3.09% | 0 | 3.43% | 0 |

| Tierra Comunera - ACAL | - | - | 1.16% | 0 | 1.19% | 0 |

Culture

Languages

Besides the dominant Castilian Spanish, three other regional languages figure in the linguistic patrimony of Castile and León. Two of these are recognized explicitly in the Statute of Autonomy. The Leonese language, according to the Statute, "will be the object of specific protection [...] for its particular value in the linguistic heritage of the Community".[30] The Galician language, according to the statute, "merits respect and protection in the places where it is habitually used,[31] which is effectively to say the portions of the comarcas of El Bierzo and Sanabria bordering Galicia.

Education

- Universities

- Public

- Private

- Catholic University of Ávila (Universidad Católica Santa Teresa de Jesús de Ávila)

- Miguel de Cervantes European University (Valladolid)

- IE University (Instituto de Empresa Universidad, Segovia)

- Pontifical University of Salamanca

Demography

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 2,302,417 | — |

| 1910 | 2,362,878 | +2.6% |

| 1920 | 2,337,405 | −1.1% |

| 1930 | 2,477,324 | +6.0% |

| 1940 | 2,694,347 | +8.8% |

| 1950 | 2,864,378 | +6.3% |

| 1960 | 2,848,352 | −0.6% |

| 1970 | 2,623,196 | −7.9% |

| 1981 | 2,575,064 | −1.8% |

| 1991 | 2,562,979 | −0.5% |

| 2001 | 2,456,474 | −4.2% |

| 2011 | 2,540,188 | +3.4% |

| 2017 | 2,436,850 | −4.1% |

| Source: INE | ||

The most recent official census by the Instituto Nacional de Estadística, as January 1, 2011, gave a population of 2,540,188 (1,259,641 males and 1,280,546 females) representing 5.42 percent of the population of Spain. As of January 2011 the population of Castile and León, by province, stood as follows: Ávila, 171,647 inhabitants; Burgos, 372,538; León, 493,312; Palencia,170,513; Salamanca, 350,018; Segovia, 163,171; Soria, 94,610; Valladolid, 532,765; and Zamora, 191,613.[32]

Present-day population distribution

In 1960 only 20.6 percent of the population of present-day Castile and León was urban; by 1991 that percentage had risen to 42.3 percent. The decline in rural population has apparently been somewhat stemmed, with a 1998 statistic showing 43 percent.[citation needed]

Many rural areas became very sparsely populated in the mid-to-late 20th century. In 1986 there were seven times as many municipalities with less than 100 inhabitants as in 1960.

A recent study from University of Porto (Portugal) highlighted Castile and León - particularly the province of Salamanca - as one of the European regions where old people could expect to live longer.[33]

Notable cities include the nine provincial capitals plus Miranda de Ebro and Aranda de Duero in the province of Burgos, Ponferrada and San Andrés del Rabanedo in León, Béjar in Salamanca, and Medina del Campo and Laguna de Duero in Valladolid.

Of the 2,247 municipalities in the autonomous community, the 2000 census shows 1,970 with 1,000 or fewer inhabitants; 234 between 1,001 and 5,000; 20 between 5,001 and 10,000; 10 between 10,001 and 20,000; 6 between 20,001 and 50,000; 3 between 50,001 and 100,000; and 4 with over 100,000 inhabitants. Those last are Valladolid (319,943 in 2007), Burgos (174,075), Salamanca (159,754) and León (135,059). At the other extreme Blasconuño de Matacabras (Ávila) has a population of 18, Reinoso (Burgos) has 24, Villarmentero de Campos (Palencia), has 14, and Gormaz (Soria), 17.

| City | Population | City | Population | City | Population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Valladolid | 313,437 | Ponferrada | 68,508 | Miranda de Ebro | 38,930 | ||

| Burgos | 179,251 | Zamora | 65,525 | Aranda de Duero | 33,229 | ||

| Salamanca | 153,472 | Ávila | 59,008 | San Andrés del Rabanedo | 31,562 | ||

| León | 132,744 | Segovia | 55,220 | Laguna de Duero | 22,334 | ||

| Palencia | 81,552 | Soria | 39,987 | Medina del Campo | 21,607 |

Economy

Castile and León accounts for 5.2% of Spain's GDP.[34]

Work force

In 2001 the work force was 1,005,200 with 884,200 employed, meaning 12.1 percent of the work force were out of work. 10.9 percent of the employed population work in agriculture, 20.6 percent in industry, 12.7 percent in construction, and 63.1 percent in the service sector.

In 2007, the unemployment rate was down to 6.99 percent,[35] but the late-2000s recession drove that number up to 14.14 percent by July 2009.[36]

Primary sector

The region has nine DO wine zones, which are mostly located around the Duero valley.[37]

Some 92,600 people work in the primary sector in Castile and León, about 10 percent of employment in the region. 2001 data showed 5 percent unemployment in this sector.[citation needed]

Broken down by provinces, approximately 9,400 are employed in this sector in Ávila, 8,100 each in Burgos and Palencia, 18,300 in León, 9,200 in Salamanca, 6,400 in Segovia, 5,600 in Soria, 8,300 in Valladolid, and 14,600 in Zamora. The region's agricultural and farming sector represent 7.6% of the total in Spain.[citation needed]

Secondary sector

As of 2000, industry 18 %of the work force were engaged in industry, generating 25 percent of regional GDP. The principal industrial centres are the cities of Valladolid (21,054 workers in industry), Burgos (20,217), Aranda de Duero (4,872), León (4,521) and Ponferrada (4,270).[38]

Tourism

Tourism highlights of the region include:[39]

- Burgos Cathedral

- León Cathedral

- Zamora Cathedral

- Segovia, with its fortress

- The walls of Ávila

- City of Salamanca

- Romanic churches of Zamora

Transportation

Rail

Castilla y León has an extensive rail network, including the principal lines from Madrid to Cantabria and Galicia. The line from Paris to Lisbon crosses the region, reaching the Portuguese frontier at Fuentes de Oñoro in Salamanca. Astorga, Burgos, León, Miranda de Ebro, Palencia, Ponferrada, Medina del Campo and Valladolid are all important railway junctions.[citation needed]

Railways operate in several different gauges: Iberian gauge (1,668 mm (5 ft 5+21⁄32 in)), UIC gauge (1,435 mm (4 ft 8+1⁄2 in)) and Narrow gauge (1,000 mm (3 ft 3+3⁄8 in)). Except for some narrow-gauge lines, trains are operated by RENFE on lines maintained by the Administrador de Infraestructuras Ferroviarias (ADIF); both of these are national, state-owned companies. [citation needed]

Iberian gauge lines (ADIF/RENFE)

- Madrid - Irun

- Madrid - Burgos

- Castejón de Ebro - Bilbao

- Venta de Baños - A Coruña

- Palencia - Santander

- León - Gijón

- Medina del Campo - Santiago de Compostela

- Medina del Campo - Fuentes de Oñoro

- Torralba - Soria

- Villalba - Segovia

Narrow gauge

- León - Bilbao: Ferrocarril de La Robla, Europe's longest narrow-gauge line, operated by FEVE

- Cercedilla - Cotos: operated by RENFE

- Ponferrada - Villablino: operated by the Ferrocarril MSP under the Junta of Castile and León

Roads

The region is also crossed by two major ancient routes:[citation needed]

- The Way of St. James, mentioned above as a World Heritage Site, now a hiking trail and a motorway, from east to west.

- The Roman Via de la Plata ("Silver Way"), mentioned above in the context of mining, now a main road through the west of the region.

The road network is regulated by the Ley de carreteras 10/2008 de Castilla y León (Highway Law 10/2008 of Castile and León).[40] This law allows for the possibility of roads financed by the private sector through concessions, as well as the public construction of roads that has long prevailed. [citation needed]

Nature

Flora and vegetation

The solitary oaks and junipers now found on the Castilian-Leonese plains are remnants of forests that once covered these lands. Agricultural exploitation—cultivation of cereals and creation of pastures for the vast flocks of the Castilian Meseta—meant the deforestation of these lands during the Middle Ages.[citation needed]

Wide extensions of oak survive on the lower slopes of the Sistema Central. Higher up, between 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) and 1,000 metres (3,300 ft) altitude, chestnuts are abundant. Nonetheless, many oak forests have disappeared, cut down and replaced by pines. The principal native pine forests are in the Sierra de Guadarrama. The subalpine zones between 1,700 metres (5,600 ft) and 2,200 metres (7,200 ft) are home to shrubs and juniper. [citation needed]

Fauna

The mountain rivers provide a habitat for nutrias and Pyrenean desmans, not to mention trout, freshwater eels, bighead carp and some increasingly rare native freshwater crabs. Mammals include the otter (Lutra lutra) and desman (Galemys pyrenaicus). In the lower depths of the river are the barbels (Barbus barbus) and carp. Local amphibians include newts, the Almanzor salamander (Salamandra salamandra almanzoris, a subspecies of fire salamander) and the Gredos toad (Bufo bufo gredosicola, a supspecies of common toad); the latter two are endemic to the Sistema Central. [citation needed]

Among the birds that populate the open Mediterranean forests are two endangered species: the black stork (Ciconia nigra) and the Spanish imperial eagle (also known as Iberian imperial eagle or Adalbert's eagle, Aquila adalberti). [citation needed]

Castilla y Leon contains around 30% of the world's great bustard (Otis tarda) population.[41]

After many centuries disappeared from the Iberian Peninsula, the European bison is being reintroduced in the region.[42]

See also

Notes

- ^ "El PP renuncia a solicitar la capitalidad para evitar conflictos entre provincias" (in Spanish). El Mundo. Retrieved 10 October 2013.

- ^ Article 1 of the Project of Federal Constitution of the First Spanish Republic, July 17, 1873.

- ^ Investigaciones históricas. Valladolid. Secretariado de Publicaciones, Universidad de Valladolid, 1979.

- ^ Juan-Miguel Álvarez Domínguez.The Regionalist Catechism of Don Eugenio, an example of Castilian-Leonese regionalism sponsored by León. 1931, Argutorio, No. 19 (2nd semester 2007), pp. 32-36.

- ^ Diario de León (newspaper), May 22, 1936.

- ^ a b c d e Cite error: The named reference

Statutewas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ {{web cite | author = Fundación Las Edades del Hombre | title = Objectivos - Fundación Las Edades del Hombre. | url = http://www.lasedades.es/contentobjetivos.htm | urlarchive = https://web.archive.org/web/20110720003124/http://www.lasedades.es/contentobjetivos.htm | datearchive = 20 of julio of 2011 }}

- ^ {{web cite | title = Vive Tosacana | url = http://www.vivetoscana.com.ar/patrimonio-de-la-humanidad-de-la-unesco-en-toscana/ }}

- ^ {{web cite | author = Unesco: World Heritage Conservation | title = Italy | url = http://whc.unesco.org/en/statesparties/it | language = English }}

- ^ "Europe & North America (289 biosphere reserves in 34 countries)". Unesco. June 2014.

- ^ María R. Mayor (June 19, 2013), "Unesco recognizes León as the worldwide cradle of parliamentarism", El Mundo (newspaper)

- ^ {{web cite | author = UNESCO: Memory of the World Programme | title = Memory of the World Programme - Spain | url = http://www.unesco.org/new/es/communication-and-information/flagship-project-activities/memory-of-the-world/register/access-by-region-and-country/europe-and-north-america/spain/ }}

- ^ {{cite | url = http://www.directoressociales.com/images/Dec2015/Folleto%20Indice%20DEC%202015.pdf | title = Índice de desarrollo de los servicios sociales 2015 | publisher = Asociación Estatal de Directores y Gerentes en Servicios Sociales | year = 2016 }}

- ^ Cite error: The named reference

PISA 2015was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Cortes Generales (1995), "Organic Law 10/1995, of November 23 , of the Penal Code" (PDF), Boletín Oficial del Estado no. 281, of November 24, 1995, Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado

- ^ http://www.elnortedecastilla.es/leon/201408/13/santo-grial-eleva-visitas-20140813125836.html

- ^ http://www.abc.es/local-castilla-leon/20140326/abci-historiadores-concluyen-santo-grial-201403261750.html

- ^ Artículo 1, Proyecto Constitución Federal de la I República Española, 17 de julio de 1873

- ^ Investigaciones históricas. Valladolid: Secretariado de Publicaciones, Universidad de Valladolid, 1979

- ^ Juan-Miguel Alvarez Dominguez, "El Catecismo Regionalista de Don Eugenio, un ejemplo de regionalismo castellanoleonés patrocinado desde León (1931)", Argutorio, nº 19 (2º semestre 2007), pp. 32-36.

- ^ «unir en una personalidad a León y Castilla la Vieja en torno a la gran cuenca del Duero, sin caer ahora en rivalidades pueblerinas». Diario de León, 22 de mayo de 1936.

- ^ "Seis grupos políticos se fusionan en un partido regionalista en Castilla y León". Elpais.com. Retrieved 2010-10-03.

- ^ Tribunal Constitucional Española, Sentencia 89/1984, fundamento de derecho 5, September 28, 1984.

- ^ Diario de León, 5 de mayo de 1984.

- ^ Diario de León, 13 de marzo de 2004.

- ^ "Castilla y León and La Rioja". Rough Guides. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ^ "Climate in Castilla y Leon". IberiaNature. Retrieved 6 March 2015.

- ^ Elecciones Municipales 2011 (El País).

- ^ Resultados autonómicos de Castilla y León Archived August 18, 2007, at archive.today (Cinco Días).

- ^ "será objeto de protección específica [...] por su particular valor dentro del patrimonio lingüístico de la Comunidad"

- ^ "gozará de respeto y protección en los lugares en que habitualmente se utilice"

- ^ National Statistics Institute

- ^ Ribeiro, Ana Isabel; Krainski, Elias Teixeira; Carvalho, Marilia Sá; Pina, Maria de Fátima de (2016-02-15). "Where do people live longer and shorter lives? An ecological study of old-age survival across 4404 small areas from 18 European countries". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 70: jech–2015-206827. doi:10.1136/jech-2015-206827. ISSN 1470-2738. PMID 26880296.

- ^ "Castilla y Leon". Internal Market, Industry. European Commission. Retrieved 10 December 2015. (login required)

- ^ El paro bajó en Castilla y León un 5% frente a un incremento nacional del 6,5, El Mundo, 2008-01-26. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ^ El paro sube en la Comunidad en 5.000 personas en el segundo trimestre, rtvcyl.es, 2009-07-24. Retrieved 2009-11-30.

- ^ "Castilla y Leon wines". Wine-Searcher. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ Fichas Municipales - 2008 DATOS ECONÓMICOS Y SOCIALES, Caja España, 2008. Archived December 22, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Introducing Castilla y León". Lonely Planet. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ Ha entrado en vigor la nueva Ley de carreteras de Castilla y León que regula la planificación, proyección, construcción, conservación, financiación, uso y explotación de las carreteras con itinerario comprendido íntegramente en el territorio de la Comunidad Autónoma de Castilla y León y que no sean de titularidad del Estado. [1][dead link]

- ^ Carlos A Martín, Carmen Martínez, Luis Miguel Bautista and Beatriz Martín (June 2012). "Population increase of the great bustard Otis tarda in its main distribuiton area in relation to changes in farming practice". Ardeola. 59 (1). SEO/BirdLife: 31–42. doi:10.13157/arla.59.1.2012.31.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ http://www.elmundo.es/elmundo/2010/06/04/castillayleon/1275667194.html