Toledo, Spain: Difference between revisions

| Line 532: | Line 532: | ||

*Convent Convento de las Comendadoras de Santiago: The Convent of the Comendadoras of Santiago occupies, since 1935, the Cloister of the Mona, part of the monastery of Santo Domingo el Real of Toledo. Located at the northern end of this monastery, the old Santo Domingo refectory is preserved, with a pottery dating to the end of the 15th century. The main courtyard, called de la Mona, was built after the construction of the new Dominican church, begun in 1565, most likely by Don Diego de Velasco. The cloister was designed by Diego de Alcántara, who formed with [[Juan de Herrera]] and acted as a rigger in the Alcázar of Toledo, which also gave the traces of iron railings, balusters and [[azulejos]]. |

*Convent Convento de las Comendadoras de Santiago: The Convent of the Comendadoras of Santiago occupies, since 1935, the Cloister of the Mona, part of the monastery of Santo Domingo el Real of Toledo. Located at the northern end of this monastery, the old Santo Domingo refectory is preserved, with a pottery dating to the end of the 15th century. The main courtyard, called de la Mona, was built after the construction of the new Dominican church, begun in 1565, most likely by Don Diego de Velasco. The cloister was designed by Diego de Alcántara, who formed with [[Juan de Herrera]] and acted as a rigger in the Alcázar of Toledo, which also gave the traces of iron railings, balusters and [[azulejos]]. |

||

*Convent Convento de la Madre de Dios: The Baroque and Renaissance and Mudéjar convent of Madre de Dios was founded in 1482 as beguine by Dona Leonor and Dona María de Silva. Shortly afterwards it became a monastery, which went through periods of crisis during the 17th and 18th centuries as a result of the lack of religious and confiscation. The nuns return to the convent in 1851 by express wish of [[Isabel II]], who rehabilitates the facilities to house the new community. Two decades later the nuns are expelled again and the building becomes the headquarters of the [[civil guard]]. In the early 20th century it is returned to the community, but the nuns are forced to leave the temple as a result of its poor state of conservation. In the late 1990s, the University acquired the property from a Dominican congregation with the aim of expanding its dependencies. After the rehabilitation of the former Convent of Madre de Dios, carried out between 2002 and 2005, the Faculty of Legal and Social Sciences of Toledo. |

|||

*Convent Convento de Santa Úrsula: Is the first church of Mudéjar style founded in Toledo in 1360. There are important remnants of the church, highlighting the wooden roof in the sacristy, the tajuel de lacería, forming stars of eight and sixteen points, with cupolas of mocárabes. |

|||

*Convent Convento de San Antonio de Padua: It was a beguinage of women, founded in 1514, that had its soothes in houses located in front of the cover of the conventual church of the Dominicans of the Madre de Dios. In 1525, the beatas bought the palace or house of the alderman regent Hernando de Ávalos, which had been confiscated, by order of [[Charles V]]. This palace of Ávalos will be the nucleus of the convent of San Antonio de Padua, with other additions of neighboring properties. The traces, for the conventual church, is due to Juan Bautista Monegro; But who finished the works was [[Juan Martínez Encabo]].<ref>[http://toledoguiaturisticaycultural.com/convento-de-san-antonio-de-padua/ toledoguiaturisticaycultural.com/convento-de-san-antonio-de-padua/]</ref> |

|||

*Convent Convento de Santo Domingo el Real: It was founded in 1364 by Inés García de Meneses, widow of sheriff Sanz de Velasco. Dona Inés gave her houses (her residence and attached pens) for this purpose and was prioress for many years, until her death. Soon the new enclosure became a favorite place of recollection for [[infanta]]s and ladies of the royal court, for the "clean and spacious" of the house, as recorded in several documents. The house keeps in its archives numerous documents of the descendants of the king Pedro, since it became "place of memory" of the king. The convent is a large space made up of several buildings of different epoch and construction in which all styles are superimposed. |

|||

*Convent Convento de las Capuchinas: The Convent of the Purísima Concepción, also known as las Capuchinas by the congregation of nuns who live among its walls, was originally founded by nuns of this order who arrived from Madrid in March 1632, at the request of Doña Petronila Yáñez, Widow of Don Pedro Laso Coello and very wealthy neighbor of Toledo. She installed them in her house of provisional way in which also it enabled a church. In 1635, they were transferred to other houses and in 1655, Cardinal Pascual de Aragón, who is buried in his church, took them to other houses that he bought from Don Juan de Isasaga y Mendoza. Finally, this same Cardinal, being Archbishop of Toledo, began to build them the convent and the church that we contemplate today, beginning the works in 1666 and ending in 1671 those of the temple and in 1673 those of the convent. The building, constructed in brick by the architect Bartolomé Zumbigo y Salcedo (who would become master of works of the Cathedral), presents a facade that in the church fulfills the function of altarpiece. The front is finished by a pediment in the form of a triangle with an oculus in the center. In the niche we see, there is an Immaculate Virgin whose work is attributed to the Madrilenian sculptor Manuel Pereira. Already in the interior, its plant is rectangular and consists of a single nave covered with a vault of half cannon with lunetos. The main altarpiece is the work of the Italian Virgilio Fanelli, while the paintings are by Francisco Rizzi. On the other hand, the canvases on the sides are cupboards in the interior of which are kept numerous reliquaries. |

|||

To mark the fourth centenary of the publication of the first part of ''[[Don Quixote]]'', the Council of Communities of Castile–La Mancha designed a series of routes through the region crossing the various points cited in the novel. Known as the Route of Don Quixote, two of the pathways designated, sections 1 and 8, are based in Toledo; those linking the city with La Mancha Castile and Montes de Toledo exploit the natural route which passes through the Cigarrales and heads to Cobisa, Nambroca Burguillos of Toledo, where it takes the Camino Real from Sevilla to suddenly turn towards Mascaraque Almonacid de Toledo, deep into their surroundings, near Mora, in La Mancha. |

To mark the fourth centenary of the publication of the first part of ''[[Don Quixote]]'', the Council of Communities of Castile–La Mancha designed a series of routes through the region crossing the various points cited in the novel. Known as the Route of Don Quixote, two of the pathways designated, sections 1 and 8, are based in Toledo; those linking the city with La Mancha Castile and Montes de Toledo exploit the natural route which passes through the Cigarrales and heads to Cobisa, Nambroca Burguillos of Toledo, where it takes the Camino Real from Sevilla to suddenly turn towards Mascaraque Almonacid de Toledo, deep into their surroundings, near Mora, in La Mancha. |

||

Revision as of 23:48, 1 February 2017

Toledo | |

|---|---|

City | |

| |

| Country | |

| Autonomous Community | |

| Province | Toledo |

| Comarca | Toledo |

| Partido judicial | Toledo |

| Settled | Pre-Roman |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Milagros Tolón (PSOE) |

| Area | |

| • Land | 232.1 km2 (89.6 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 529 m (1,736 ft) |

| Population (2012)INE | |

| • Total | 84,019 |

| Postcode | 45001-45009 |

| Area code | +34 |

| Website | http://www.ayto-toledo.org/ |

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Historic City of Toledo | |

| Location | Spain |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 379 |

| Inscription | 1986 (10th Session) |

Toledo (Spanish: [toˈleðo]) is a city and municipality located in central Spain, it is the capital of the province of Toledo and the autonomous community of Castile–La Mancha. It was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1986 for its extensive cultural and monumental heritage and historical co-existence of Christian, Muslim and Jewish cultures.

Toledo is known as the "Imperial City" for having been the main venue of the court of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, and as the "City of the Three Cultures", having been influenced by a historical co-existence of Christians, Muslims and Jews. Toledo has a history in the production of bladed weapons, which are now popular souvenirs of the city.

People who were born or have lived in Toledo include Brunhilda of Austrasia, Al-Zarqali, Garcilaso de la Vega, Eleanor of Toledo, Alfonso X and El Greco. It was also the place of important historic events such as the Visigothic Councils of Toledo. As of 2015[update], the city has a population of 83,226[1] and an area of 232.1 km2 (89.6 sq mi).

Coat of arms

The town was granted arms in the 16th century, which by special royal privilege was based on the royal of arms of Spain.

History

Antiquity

Toledo (Latin: Toletum) is mentioned by the Roman historian Livy (ca. 59 BCE – 17 CE) as urbs parva, sed loco munita ("a small city, but fortified by location"). Roman general Marcus Fulvius Nobilior fought a battle near the city in 193 BCE against a confederation of Celtic tribes including the Vaccaei, Vettones, and Celtiberi, defeating them and capturing a king called Hilermus.[2][3] At that time, Toletum was a city of the Carpetani tribe, and part of the region of Carpetania.[4] It was incorporated into the Roman Empire as a civitas stipendiaria, that is, a tributary city of non-citizens. It later achieved the status of municipium by Flavian times.[5] With this status, city officials, even of Carpetani origin, obtained Roman citizenship for public service, and the forms of Roman law and politics were increasingly adopted.[6] At approximately this time were constructed in Toletum a Roman circus, city walls, public baths, and a municipal water supply and storage system.[7]

The Roman circus in Toledo was one of the largest in Hispania, at 423 metres (1,388 feet) long and 100 metres (330 feet) wide, with a track dimension of 408 metres (1,339 feet) long and 86 metres (282 feet) wide.[7] Chariot races were held on special holidays and were also commissioned by private citizens to celebrate career achievements. A fragmentary stone inscription records circus games paid for by a citizen of unknown name to celebrate his achieving the sevirate, a kind of priesthood conferring high status. Archaeologists have also identified portions of a special seat of the sort used by the city elites to attend circus games, called a sella curulis. The circus could hold up to 15000 spectators.[7]

During Roman times, Toledo was never a provincial capital nor a conventus iuridicus.[8] It started to gain importance in late antiquity. There are indications that large private houses (domus) within the city walls were enlarged, while several large villas were built north of the city through the third and fourth centuries.[9] Games were held in the circus into the late fourth and early fifth centuries C.E., also an indication of active city life and ongoing patronage by wealthy elites.[10] A church council was held in Toledo in the year 400 to discuss the conflict with Priscillianism.[11] A second council of Toledo was held in 527. The Visigothic king Theudis was in Toledo in 546, where he promulgated a law. This is strong though not certain evidence that Toledo was the chief residence for Theudis.[8] King Athanagild died in Toledo, probably in 568. Although Theudis and Athangild based themselves in Toledo, Toledo was not yet the capital city of the Iberian peninsula, as Theudis and Athangild's power was limited in extent, the Suevi ruling Galicia and local elites dominating Lusitania, Betica, and Cantabria.[12][13] This changed with Liuvigild (Leovigild), who brought the peninsula under his control. The Visigoths ruled from Toledo until the Moors conquered the Iberian peninsula in the early years of 8th century (711–719).

Today the historic center is pierced of basements, passages, wells, baths and ancient water pipes that since Roman times have been used in the city.

Visigothic Toledo

A series of church councils was held in Toledo under the Visigoths. A synod of Arian bishops was held in 580 to discuss theological reconciliation with Nicene Christianity.[14] Liuvigild's successor, Reccared, hosted the third council of Toledo, at which the Visigothic kings abandoned Arianism and reconciled with the existing Hispano-Roman episcopate.[15] A synod held in 610 transferred the metropolitanate of the old province of Carthaginensis from Cartagena to Toledo.[16] At that time, Cartagena was ruled by the Byzantines, and this move ensured a closer relation between the bishops of Spain and the Visigothic kings. King Sisebut forced Jews in the Visigothic kingdom to convert to Christianity; this act was criticized and efforts were made to reverse it at the Fourth Council of Toledo in 633.[17] The Fifth and Sixth Councils of Toledo placed church sanctions on anyone who would challenge the Visigothic kings.[18] The Seventh Council of Toledo instituted a requirement that all bishops in the area of a royal city, that is, of Toledo, must reside for one month per year in Toledo. This was a stage in "the elevation of Toledo as the primatial see of the whole church of the Visgothic kingdom".[19] In addition, the seventh council declared that any clergy fleeing the kingdom, assisting conspirators against the king, or aiding conspirators, would be excommunicated and no one should remove this sentence. The ban on lifing these sentences of excommunication was lifted at the Eighth Council of Toledo in 653, at which, for the first time, decisions were signed by palace officials as well as bishops.[20]

The eighth council of Toledo took measures that enhanced Toledo's significance as the center of royal power in the Iberian peninsula. The council declared that the election of a new king following the death of the old one should only take place in the royal city, or wherever the old king died.[21] In practice this handed the power to choose kings to only such palace officials and military commanders who were in regular attendance on the king. The decision also took king-making power away from the bishops, who would be in their own sees and would not have time to come together to attend the royal election. The decision did allow the bishop of Toledo, alone among bishops, to be involved in decisions concerning the royal Visigothic succession. The ninth and tenth councils were held in rapid succession in 655 and 656.[21]

When Reccesuinth died in 672 at his villa in Gerticos, his successor Wamba was elected on the spot, then went to Toledo to be anointed king by the bishop of Toledo, according to the procedures laid out in prior church councils.[22] In 673, Wamba defeated a rebel duke named Paul, and held his victory parade in Toledo. The parade included ritual humiliation and scalping of the defeated Paul.[23] Wamba carried out renovation works in Toledo in 674-675, marking these with inscriptions above the city gates that are no longer extant but were recorded in the eighth century.[24] The Eleventh Council of Toledo was held in 675 under king Wamba. Wamba weakened the power of the bishop of Toledo by creating a new bishopric outside Toledo at the church of Saints Peter and Paul. This was one of the main churches of Toledo and was the church where Wamba was anointed king, and the church from which Visigothic kings departed for war after special ceremonies in which they were presented with a relic of the True Cross. By creating a new bishopric there, Wamba removed power over royal succession from the bishop of Toledo and granted it to the new bishop.[25] The Twelfth Council of Toledo was held in 681 after Wamba's removal from office. Convinced that he was dying, Wamba had accepted a state of penitence that according to the decision of a previous church council, made him inelegible to remain king. The Twelfth Council, led by newly installed bishop Julian confirmed the validity of Wamba's removal from office and his succession by Ervig. The Twelfth Council eliminated the new bishopric that Wamba had created and returned the powers over succession to the bishop of Toledo.[26]

The Twelfth Council of Toledo approved 28 laws against the Jews. Julian of Toledo, despite a Jewish origin, was strongly anti-Semitic as reflected in his writings and activities.[27] The leading Jews of Toledo were assembled in the church of Saint Mary on January 27, 681, where the new laws were read out to them.

The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Councils of Toledo were held in 683, 684, and 688. The Thirteenth Council restored property and legal rights to those who had rebelled against King Wamba in 673.[28] The Thirteenth Council also approved laws protecting the king's family after the king's death. In 687, Ervig took the penitent state before dying, and the kingship passed to Egica, who was anointed king in Toledo on November 24.[29] In 688, the Fifteenth Council lifted the ban on taking property from the families of former kings, whereupon Egica was able to plunder Ervig's family properties.[30]

In the late seventh century, Toledo became a main center of literacy and writing in the Iberian peninsula. Toledo's development as a center of learning was influenced by Isidore of Seville, an author and advocate of literacy who attended several church councils in Toledo.[31] King Chindasuinth had a royal library in Toledo, and at least one count called Laurentius had a private library.[32] Sometime before 651, Chindasuinth sent the bishop of Zaragoza, Taio, to Rome to obtain books that were not available in Toledo. Taio obtained, at least, parts of pope Gregory's Moralia.[33] The library also contained a copy of a Hexameron by Dracontius, which Chindasuinth liked so much that he commissioned Eugenius II to revise it by adding a new part dealing with the seventh day of creation.[34] Chindasuinth issued laws that were gathered together in a book called Liber Iudiciorum by his successor Reccesuinth in 654; this book was revised twice, widely copied, and was an important influence on medieval Spanish law.[35] Three bishops of Toledo wrote works that were widely copied and disseminated in western Europe and parts of which survive to this day: Eugenius II, Ildefonsus, and Julian.[36] "In intellectual terms the leading Spanish churchmen of the seventh century had no equals before the appearance of Bede."[37]

In 693, the Sixteenth Council of Toledo condemned Sisebert, Julian's successor as bishop of Toledo, for having rebelled against King Egica in alliance with Liuvigoto, the widow of king Ervig.[38] A rebel king called Suniefred seized power in Toledo briefly at about this time. Whether or not Sisebert's and Suniefred's rebellions were the same or separate is unknown. Suniefred is known only from having minted coins in Toledo during what should have been Egica's reign.[39] The Seventeenth Council of Toledo was held in 694. The Eighteenth Council of Toledo, the last one, took place shortly after Egica's death around 702 or 703.[40]

By the end of the seventh century the bishop of Toledo was the leader of the Spanish bishops, a situation unusual in Europe: "The metropolitan bishops of Toledo had achieved by the last quarter of the seventh century an authority and a primacy that was unique in Western Europe. Not even the pope could count on such support from neighbouring metropolitans."[37] Toledo "had been matched by no other city in western Europe outside Italy as the governmental and symbolic center of a powerful monarchy."[41] Toledo had "emerged from relative obscurity to become the permanent governmental centre of the Visigothic monarchy; a true capital, whose only equivalent in western Europe was to be Lombard Pavia."[42]

When Wittiza died around 710, Ruderic became Visigothic king in Toledo, but the kingdom was split, as a rival king Achila ruled Tarraconensis and Narbonensis.[43] Meanwhile, Arabic and Berber troops under Musa ibn Nusayr had conquered Tangiers and Ceuta between 705 and 710, and commenced raids into the Visigothic kingdom in 711.[44] Ruderic led an army to confront the raiders. He was defeated and killed in battle, apparently after being betrayed by Visigothic nobles who wished to replace him as king and did not consider the Arabs and Berbers a serious threat. The commander of the invading forces was Tariq bin Ziyad, a Luwata Berber freedman in the service of governor Musa.[45] It is possible that a king called Oppa ruled in Toledo between Ruderic's death and the fall of Toledo.[46] Tariq, seizing the opportunity presented by the death of Ruderic and the internal divisions of the Visigothic nobles, captured Toledo, in 711 or 712.[47] Governor Musa disembarked in Cádiz and proceeded to Toledo, where he executed numerous Visigothic nobles, thus destroying much of the Visigothic power structure.[48][49] Collins suggests that the Visigothic emphasis on Toledo as the center of royal ceremony became a weakness. Since the king was chosen in or around Toledo, by nobles based in Toledo, and had to be anointed king by the bishop of Toledo in a church in Toledo, when Tariq captured Toledo and executed the Visigothic nobles, having already killed the king, there was no way for the Visigoths to select a legitimate king.[50][51]

Toledo under Arab rule

Soon after the conquest, Musa and Tariq returned to Damascus. The Arab center of administration was placed first in Seville, then moved to Cordoba. With most of the rest of the Iberian peninsula, Toledo was ruled from Cordoba by the governor of Al-Andalus, under the ultimate notional command of the Umayyad Caliph in Damascus. Arab conquerors had often replaced former capital cities with new ones to mark the change in political power, and they did so here: "Toledo suffered a period of profound decline throughout much of the earlier centuries of Arab dominance in the peninsula."[52] The invaders were ethnically diverse, and available evidence suggests that in the area of Toledo, Berber settlement predominated over Arab.[53]

In 742 the Berbers in Al-Andalus rebelled against the Arab Omeyyad governors. They took control of the north and marched south, laying siege to Toledo. After a siege of one month the Berber troops were defeated outside Toledo by troops sent from Cordoba by the governor Abd al-Malik ibn Katan and commanded by the governor's son.[54] However, while Ibn Katan's troops were engaged with the Berbers, his Arab allies betrayed and killed him and took over Cordoba. After the Arabs' first leader, Talama ibn Salama, died, Yusuf al-Fihri became ruler of Al-Andalus. The Omeyyad dynasty in Damascus collapsed and Yusuf ruled independently with the support of his Syrian Arab forces. The Qays Arab commander As-Sumayl was made governor of Toledo under Yusuf around 753.[55]

There is evidence that Toledo retained its importance as a literary and ecclesiastical center into the middle 700s, in the Chronicle of 754, the life of Saint Ildefonsus by Cixila, and ecclesiastical letters sent from Toledo.[56] The eighth century bishop of Toledo, Cixila, wrote a life of Saint Ildefonsus of Toledo, probably before 737.[57] This life of Ildefonsus emphasized two episodes in the life of the bishop of Toledo. In the first episode the covering of the tomb of Saint Leocadia levitated while Ildefonsus was saying mass, with king Reccesuinth present. In the second episode Mary appears to Ildefonsus and Reccesuinth. These episodes are said to have resulted from Ildefonsus' devotion to Saint Leocadia, patroness saint of Toledo.[58] Collins suggests that Cixila's life of Ildefonsus helped maintain Ildefonsus' appeal and helped the church in Toledo to retain some of its authority among Christian churches in the Iberian peninsula.[59]

An archdeacon in Toledo called Evantius, who was active around 720 and died in 737, wrote a letter to address the existence of judaizing tendencies among the Christians of Zaragoza, specifically the belief that there are unclean forms of meat and the literal interpretation of Deuteronomic law.[60] A deacon and cantor from Toledo called Peter wrote a second letter, to Seville, in about the year 750, to explain that they were celebrating Easter and a September liturgical fast incorrectly, again confusing them with Jewish feasts celebrated at the same time.[61] These letters show that some of the primacy of the church of Toledo within the Iberian peninsula still existed in the 700s: "Not only were its clerics still well enough equipped in intellectual terms to provide authoritative guidance on a wide range of ecclesiastical discipline and doctrine, but this was also actively sought."[62]

There is a strong possibility that the Chronicle of 754 was written in Toledo (though scholars have also proposed Cordoba and Guadix) based on the information available to the chronicler.[63] The chronicler showed awareness of the Historia Gothorum, the Etymologiae, and the chronicle of Isidore of Seville, the work of Braulio of Zaragoza, the acts of the councils of Toledo, De Perpetua Virginitate by Ildefonsus, and De Comprobatione Sextae Aetatis and Historia Wambae by Julian of Toledo, all works that would have existed in the Visigothic libraries of seventh century Toledo and whose existence together "makes more sense in a Toledan context than in any other."[64]

In 756 Abd ar-Rahman, a descendant of the fallen Omeyyad caliphs, came to Al-Andalus and initiated a revolt against Yusuf. He defeated Yusuf and forced him to reside in Cordoba, but Yusuf broke the agreement and raised a Berber army to fight Abd ar-Rahman. In this conflict, Toledo was held against Abd ar-Rahman by Yusuf's cousin Hisham ibn Urwa. Yusuf attempted to march on Seville, but was defeated and instead attempted to reach his cousin in Toledo. He was either killed on his way to Toledo, or he reached Toledo and held out there for as many as two or three years before being betrayed and killed by his own people. Whether or not Yusuf himself held out in Toledo, Hisham ibn Urwa did hold power in Toledo for several years, resisting the authority of Abd ar-Rahman. In 761 Hisham is reported as again being in rebellion in Toledo against Abd ar-Rahman. Abd ar-Rahman failed to take Toledo by force and instead signed a treaty allowing Hisham to remain in control of Toledo, but giving one of his sons as hostage to Abd ar-Rahman. Hisham continued to defy Abd ar-Rahman, who had Hisham's son executed and the head catapulted over the city walls into Toledo. Abd ar-Rahman attacked Toledo in 764, winning only when some of Hisham's own people betrayed him and turned him over to Abd ar-Rahman and his freedman Badr.[65] Ibn al-Athir states that towards the end of Abd ar-Rahman's reign, a governor of Toledo raided in force into the Kingdom of Asturias during the reign of Mauregatus,[66] though the Asturian chronicles do not record the event.[67]

Under the Umayyad Emirate of Cordoba, Toledo was the centre of numerous insurrections dating from 761 to 857.[68] Twenty years after the rebellion of Hisham ibn Urwa, the last of Yusuf's sons, Abu al-Aswad ibn Yusuf, rebelled in Toledo in 785.[69][70] After the suppression of ibn Yusuf's revolt, Abd ar-Rahman's oldest son Sulayman was made governor of Toledo. However, Abd ar-Rahman designated as his successor a younger son, Hisham. On Hisham's accession to the Emirate in 788, Sulayman refused to make the oath of allegiance at the mosque, as succession custom would have dictated, and thus declared himself in rebellion. He was joined in Toledo by his brother Abdallah. Hisham laid siege to Toledo. While Abdallah held Toledo against Hisham, Sulayman escaped and attempted to find support elsewhere, but was unsuccessful. In 789, Abdallah submitted and Hisham took control of Toledo. The following year, Sulayman gave up the fight and went into exile.[71] Hisham's son Al-Hakam was governor of Toledo from 792 to 796 when he succeeded his father as emir in Cordoba.

After Al-Hakam's accession and departure, a poet resident in Toledo named Girbib ibn-Abdallah wrote verses against the Omeyyads, helping to inspire a revolt in Toledo against the new emir in 797. Chroniclers disagree as to the leader of this revolt, though Ibn Hayyan states that it was led by Ibn Hamir. Al-Hakam sent Amrus ibn Yusuf to fight the rebellion. Amrus took control of the Berber troops in Talavera. From there, Amrus negotiated with a faction inside Toledo called the Banu Mahsa, promising to make them governors if they would betray Ibn Hamir. The Banu Mahsa brought Ibn Hamir's head to Amrus at Talavera, but instead of making them governors, Amrus executed them. Amrus now persuaded the remaining factions in Toledo to submit to him. Once he entered Toledo, he invited the leaders to a celebratory feast. As they entered Amrus' fortress, the guests were beheaded one by one and their bodies thrown in a specially dug ditch. The massacre was thus called "The Day of the Ditch." Amrus' soldiers killed about 700 people that day. Amrus was governor of Toledo until 802.[72][73]

"In 785, Bishop Elipandus of Toledo wrote a letter condemning the teaching of a certain Migetius."[74] In his letter, Elipandus asserted that Christ had adopted his humanity, a position that came to be known as Adoptionism.[75] Two Asturian bishops, Beatus and Eterius, bishop of Osma, wrote a treatise condemning Elipandus' views.[76] Pope Hadrian wrote a letter between 785 and 791 in which he condemned Migetius, but also the terminology used by Elipandus.[77] The Frankish court of Charlemagne also condemned Adoptionism at the Synod of Frankfurt in 794.[78] Although Ramon Abadals y de Vinyals argued that this controversy represented an ideological assertion of independence by the Asturian church against the Moslem-ruled church of Toledo,[79] Collins believes this argument applies eleventh century ideology to the eighth century and is anachronistic.[80] However, Collins notes that the controversy and the alliances formed during it between Asturias and the Franks broke the old unity of the Spanish church.[81] The influence of the bishops of Toledo would be much more limited until the eleventh century.[82]

By the end of the 700s, the Omeyyads had created three frontier districts stretching out from the southern core of their Iberian territories. These were called Lower March (al-Tagr al-Adna), Central March (al-Tagr al-Awsat), and Upper March (al-Tagr al-A'la). Toledo became the administrative center of the Central March, while Merida became the center of the Lower March and Zaragoza, of the Upper March.[83]

Following the death of Abd al-Rahman II, a new revolt broke out in Toledo. The Omeyyad governor was held hostage in order to secure the return of Toledan hostages held in Córdoba. Toledo now engaged in an inter-city feud with the nearby city of Calatrava la Vieja. Toledan soldiers attacked Calatrava, destroyed the walls, and massacred or expelled many inhabitants of Calatrava in 853. Soldiers from Cordoba came to restore the walls and protect Calatrava from Toledo. The new emir, Muhammad I, sent a second army to attack the Toledans, but was defeated. Toledo now made an alliance with King Ordoño I of Asturias. The Toledans and Asturians were defeated at the Battle of Guadacelete, with sources claiming 8000 Toledan and Asturian soldiers were killed and their heads sent back to Cordoba for display throughout Al-Andalus. Despite this defeat, Toledo did not surrender to Cordoba. The Omeyyads reinforced nearby fortresses with cavalry forces to try to contain the Toledans. Toledans attacked Talavera in 857, but were again defeated. In 858 emir Muhammad I personally led an expedition against Toledo and destroyed a bridge, but was unable to take the city. In 859, Muhammad I negotiated a truce with Toledo. Toledo became virtually independent for twenty years, though locked in conflict with neighboring cities. Muhammad I recovered control of Toledo in 873, when he successfully besieged the city and forced it to submit.[84]

The Banu Qasi gained nominal control of the city until 920 and in 932 Abd-ar-Rahman III captured the city following an extensive siege.[85] According to the Chronicle of Alfonso III, Musa ibn Musa of the Banu Qasi had, partly by war and partly by strategy, made himself master of Zaragoza, Tudela, Huesca, and Toledo. He had installed his son Lupus (Lubb) as governor of Toledo. King Ordoño I of Asturias fought a series of battles with Musa ibn Musa. According to the Chronicle, Musa ibn Musa allied with his brother-in-law Garcia, identified as Garcia Iñiquez, King of Pamplona. Ordoño defeated Musa's forces at the Battle of Monte Laturce. Musa died of injuries, and his son Lubb submitted to Ordoño's authority in 862 or 863, for the duration of Ordoño's reign (up to 866). Thus, according to the Chronicle of Alfonso III, Toledo was ruled by the Asturian kings. However, Arabic sources do not confirm these campaigns, instead stating that Musa ibn Musa was killed in a failed attack on Guadalajara, and that Andalusi forces repeatedly defeated Asturian forces in the area of Alava from 862 to 866.[86]

By the 870s the Omeyyads had regained control over Toledo. In 878 Al-Mundhir led an expedition against Asturias, of which one of the main components was a force from Toledo. One source portrays this raid as an attack by the 'King of Toledo', but other sources portray it as an Omeyyad raid involving substantial Toledan forces. The forces from Toledo were defeated by Alfonso III of Asturias at the Battle of Polvoraria. Spanish chronicles state that twelve to thirteen thousand in the Toledo army were killed in the battle. Collins states that these figures are "totally unreliable" but demonstrate that Asturian chroniclers thought of this as an important and decisive battle.[87]

In 920s and 930s, the governors of Toledo were in rebellion against the Umayyad regime in Cordoba, led by Abd al-Rahman III. In 930, Abd al-Rahman III, having now adopted the title of caliph, attacked Toledo.[88] The governor of Toledo asked for help from King Ramiro II of Leon, but Ramiro was preocuppied with a civil war against his brother Alfonso IV and was unable to help.[89] In 932, Abd al-Rahman III conquered Toledo, re-establishing control of al-Tagr al-Awsat, the Central March of the Omeyyad state.[90]

In 1009 one of the last Umayyad caliphs, Muhammad II al-Mahdi, fled to Toledo after being expelled from Cordoba by Berber forces backing the rival claimant Sulayman. Al-Mahdi and his Saqaliba general Wadih formed an alliance with the Count of Barcelona and his brother the Count of Urgell. These Catalans joined with Wadih and al-Mahdi in Toledo in 1010 and marched on Cordoba. The combination of Wadih's army and the Catalans defeated the Berbers in a battle outside Cordoba in 1010.[91]

After the fall of the Omeyyad caliphate in the early 11th century, Toledo became an independent taifa kingdom. The population of Toledo at this time was about 28 thousand, including a Jewish population estimated at 4 thousand.[92] The Mozarab community had its own Christian bishop, and after the Christian conquest of Toledo, the city was a destination for Mozarab immigration from the Muslim south.[93] The taifa of Toledo was centered on the Tajo River. The border with the taifa of Badajoz was on the Tajo between Talavera de la Reina and Coria. North, the border was the Sierra de Guadarrama. Northeast, Toledo lands stretched past Guadalajara to Medinaceli. Southeast was the border with the taifa of Valencia, in La Mancha between Cuenca and Albacete. South were the borders with Badajoz around the Mountains of Toledo.[94]

In 1062, Fernando I of Leon and Castile attacked the taifa of Toledo. He conquered Talamanca de Jarama and besieged Alcala de Henares. To secure Fernando's withdrawal, king al-Mamun of Toledo agreed to pay an annual tribute, or parias, to Fernando.[95] Three years later in 1065, al-Mamun invaded the taifa of Valencia through La Mancha, successfully conquering it. Toledo controlled the taifa of Valencia until al-Mamun's death in 1075.[96]

After the death of Fernando I in 1065, the kingdom of Leon and Castilla was divided in three: the kingdoms of Galicia, Leon, and Castilla. The parias that had been paid by Toledo to Fernando I were assigned to the Kingdom of León, which was inherited by Alfonso VI.[97] However, in 1071, Alfonso's older brother Sancho II invaded Leon and defeated his younger brother. Alfonso VI was allowed to go into exile with al-Mamun in Toledo.[98] Alfonso VI was in exile in Toledo approximately from June to October 1071, but after Sancho II was killed later in the same year, Alfonso left Toledo and returned to Leon. Some sources state that al-Mamun forced Alfonso to swear support for al-Mamun and his heirs before allowing him to leave.[99]

In 1074, Alfonso VI campaigned against the taifa of Granada with the assistance of al-Mamun of Toledo. Alfonso received troops from al-Mamun in addition to the parias payment, facilitating his military campaigns. The campaign was successful, and Granada was forced to begin parias payments to Alfonso VI. After this, al-Mamun proceeded to attack Cordoba, which was then under the control of his enemy al-Mutamid, taifa king of Sevilla. He conquered Cordoba in January 1075.[100]

The parias of Toledo to Alfonso VI in the 1070s amounted to approximately 12 thousand gold dinars. This money contributed strongly to Alfonso VI's ability to project military strength throughout the Iberian peninsula.[101]

In 1076, al-Mamun of Toledo was killed in the city of Cordoba, which he had conquered only the year before. The taifa king of Sevilla took the opportunity to reconquer Cordoba and seize other territory on the borderlands between the taifas of Sevilla and Toledo. Al-Mamun was succeeded by his son, al-Qadir, the last taifa king of Toledo. Possibly keeping an earlier promise to al-Mamun, Alfonso VI at first supported the succession of al-Qadir. The taifa of Valencia, which had been conquered by al-Mamun, revolted against al-Qadir and ceased parias payments to Toledo.[102]

Taking advantage of al-Qadir's weakness, al-Mutamid of Sevilla took lands in La Mancha from the taifa of Toledo, and from there conquered the taifas of Valencia and Denia in 1078. After this, al-Qadir lost popularity in Toledo. There was a revolt against him, and he was forced to flee the city and appeal to Alfonso VI for help. The rebels invited the king of Badajoz, al-Mutawakkil, to rule Toledo. The king of Badajoz occupied Toledo in 1079, but Alfonso VI sent forces to help al-Qadir recover Toledo. Alfonso captured the fortress town of Coria, which controlled a pass from Castilian lands into the lands of the taifa of Badajoz. Since Alfonso now threatened him through Coria, al-Mutawakkil withdrew from Toledo and al-Qadir was able to return to Toledo. As the price of his help, Alfonso obtained the right to station two garrisons of his soldiers on the lands of Toledo, at al-Qadir's expense.[103]

A second revolt against al-Qadir took place in 1082. This time al-Qadir defeated the rebels in Toledo, chased them to Madrid, and defeated them there.[104] It was about this time at the latest that Alfonso VI decided to seize Toledo for himself, though some authors have argued that the plan to conquer Toledo existed by 1078.[105] In 1083, Alfonso VI campaigned against al-Mutamid, bringing his forces right up against Sevilla and reaching the city of Tarifa, with the intention of dissuading al-Mutamid from any resistance against the coming seizure of Toledo.[106] In 1084, Alfonso set siege to Toledo, preventing the city from being supplied and also preventing agricultural work in the area. Over the winter of 1084 to 1085 the siege was maintained, while the king spent the winter north in Leon and Sahagun. In spring 1085 Alfonso personally rejoined the siege with new forces. The city soon fell and Alfonso made his triumphant entry to the city on May 24, 1085.

Toledo experienced a period known as La Convivencia, i.e. the co-existence of Jews, Christians, and Muslims. Under Islamic Arab rule, Toledo was called Ṭulayṭulah. After the fall of the caliphate, Toledo was the capital city of one of the richest Taifas of Al-Andalus. Its population was overwhelmingly Muladi, and, because of its central location in the Iberian Peninsula, Toledo took a central position in the struggles between the Muslim and Christian rulers of northern Spain. The conquest of Toledo by Alfonso VI of Castile in 1085 marked the first time a major city in Al-Andalus was captured by Christian forces; it served to sharpen the religious aspect of the Christian reconquest.

Medieval Toledo after the Reconquest

On May 25, 1085, Alfonso VI of Castile took Toledo and established direct personal control over the Moorish city from which he had been exacting tribute, ending the medieval Taifa's Kingdom of Toledo. This was the first concrete step taken by the combined kingdom of Leon-Castile in the Reconquista by Christian forces. After Castilian conquest, Toledo continued to be a major cultural centre; its Arab libraries were not pillaged, and a tag-team translation centre was established in which books in Arabic or Hebrew would be translated into Castilian by Muslim and Jewish scholars, and from Castilian into Latin by Castilian scholars, thus letting long-lost knowledge spread through Christian Europe again. Toledo served as the capital city of Castile intermittently (Castile did not have a permanent capital) from 1085, and the city flourished. Charles I of Spain's court was set in Toledo, serving as the imperial capital.[107] However, in 1561, in the first years of his son Philip II of Spain reign, the Spanish court was moved to Madrid, thus letting the city's importance dwindle until the late 20th century, when it became the capital of the autonomous community of Castile–La Mancha. Nevertheless, the economic decline of the city helped to preserve its cultural and architectural heritage. Today, because of this rich heritage, Toledo is one of Spain's foremost cities, receiving thousands of visitors yearly. Under the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Toledo multiple persecutions (633, 653, 693) and stake burnings of Jews (638 CE) occurred; the Kingdom of Toledo followed up on this tradition (1368, 1391, 1449, 1486–1490 CE) including forced conversions and mass murder and the rioting and blood bath against the Jews of Toledo (1212 CE).[108][109]

During the persecution of the Jews in the late 15th and early 16th centuries, members of the Jewish community of Toledo produced texts on their long history in Toledo. It was at this time that Don Isaac Abrabanel, a prominent Jewish figure in Spain in the 15th century and one of the king's trusted courtiers who witnessed the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492, wrote that Toledo was named Ṭulayṭulah by its first Jewish inhabitants who, he stated, settled there in the 5th century BCE, and which name – by way of conjecture – may have been related to its Hebrew cognate טלטול (= wandering), on account of their wandering from Jerusalem. He says, furthermore, that the original name of the city was Pirisvalle, so-called by its early pagan inhabitants.[110] However, there is no archaeological or historical evidence for Jewish presence in this region prior to the time of the Roman Empire; when the Romans first wrote about Toledo it was a Celtic city.[111][112]

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 59,000 | — |

| 1996 | 66,006 | +11.9% |

| 2001 | 68,382 | +3.6% |

| 2004 | 73,485 | +7.5% |

| 2006 | 77,601 | +5.6% |

Modern Era

Toledo's Alcázar (Latinized Arabic word for palace-castle, from the Arabic القصر, al-qasr) became renowned in the 19th and 20th centuries as a military academy. At the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War in 1936, its garrison was famously besieged by Republican forces.

Climate

Toledo has a typical cold semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSk). Winters are cool while summers are hot and dry. Precipitation is low and mainly concentrated in the period mid autumn through to mid spring. The highest temperature ever recorded in Toledo was 43.1 °C or 109.58 °F on 10 August 2012; the lowest was −9.1 °C or 15.6 °F on 27 January 2005.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 22.0 (71.6) |

23.8 (74.8) |

27.6 (81.7) |

31.6 (88.9) |

37.7 (99.9) |

42.0 (107.6) |

42.8 (109.0) |

43.1 (109.6) |

41.3 (106.3) |

33.2 (91.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

22.2 (72.0) |

43.1 (109.6) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 11.5 (52.7) |

14.0 (57.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

19.9 (67.8) |

24.2 (75.6) |

30.5 (86.9) |

34.6 (94.3) |

34.0 (93.2) |

29.0 (84.2) |

22.1 (71.8) |

15.6 (60.1) |

11.6 (52.9) |

22.1 (71.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 6.4 (43.5) |

8.3 (46.9) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.5 (56.3) |

17.6 (63.7) |

23.2 (73.8) |

26.8 (80.2) |

26.3 (79.3) |

22.0 (71.6) |

16.1 (61.0) |

10.5 (50.9) |

7.1 (44.8) |

15.8 (60.4) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 1.3 (34.3) |

2.6 (36.7) |

5.0 (41.0) |

7.2 (45.0) |

11.0 (51.8) |

15.9 (60.6) |

18.9 (66.0) |

18.6 (65.5) |

14.9 (58.8) |

10.2 (50.4) |

5.3 (41.5) |

2.5 (36.5) |

9.5 (49.1) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −9.6 (14.7) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

4.3 (39.7) |

10.0 (50.0) |

10.0 (50.0) |

5.4 (41.7) |

0.0 (32.0) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−8.0 (17.6) |

−9.6 (14.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 26 (1.0) |

25 (1.0) |

23 (0.9) |

39 (1.5) |

44 (1.7) |

24 (0.9) |

7 (0.3) |

9 (0.4) |

18 (0.7) |

48 (1.9) |

39 (1.5) |

41 (1.6) |

342 (13.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 5 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 54 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 76 | 69 | 59 | 58 | 54 | 45 | 39 | 41 | 51 | 66 | 74 | 79 | 59 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 151 | 172 | 228 | 249 | 286 | 337 | 382 | 351 | 260 | 210 | 157 | 126 | 2,922 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorologia[113] | |||||||||||||

Economy

The metal-working industry has historically been Toledo's economic base, with a great tradition in the manufacturing of swords and knives and a significant production of razor blades, medical devices and electrical products. Soap and toothpaste industries, flour milling, glass and ceramics have also been important.[114] (The Toledo Blade, the American newspaper in Toledo's Ohio namesake city, is named in honor of the sword-making tradition.)

According to the Statistical Institute of Castilla-La Mancha, in 2007 the distribution of employment by sectors of occupation was as follows: 86.5% of the population engaged in the services, 6.6% in construction, 5.4% in industry and 1.5% in agriculture and livestock.[115]

The manufacture of swords in the city of Toledo goes back to Roman times, but it was under Moorish rule and during the Reconquista that Toledo and its guild of sword-makers played a key role. Between the 15th and 17th centuries the Toledo sword-making industry enjoyed a great boom, to the point where its products came to be regarded as the best in Europe. Swords and daggers were made by individual craftsmen, although the sword-makers guild oversaw their quality. In the late 17th and early 18th century production began to decline, prompting the creation of the Royal Arms Factory in 1761 by order of King Carlos III. The Royal Factory brought together all the sword-makers guilds of the city and it was located in the former mint. In 1777, recognizing the need to expand the space, Carlos III commissioned the architect Sabatini to construct a new building on the outskirts of the city. This was the beginning of several phases of expansion. Its importance was such that it eventually developed into a city within the city of Toledo.

In the 20th century, the production of knives and swords for the army was reduced to cavalry weapons only, and after the Spanish Civil War, to the supply of swords to the officers and NCOs of the various military units. Following the closure of the factory in the 1980s, the building was renovated to house the campus of the Technological University of Castilla-La Mancha in Toledo.[116]

Goya Foods has its Madrid offices in Toledo.[117]

Unemployment

In the last decade, unemployment in absolute terms has remained fairly stable in the city of Toledo, but in 2009 this figure increased significantly: nearly 62% compared to 2008, with the number of unemployed rising from 2,515 to 4,074 (figures at 31 March each year), according to the Junta de Comunidades de Castilla La Mancha.[118] Of this 62%, one third of the increase took place in the first quarter.

According to other statistics from the same source, almost half the unemployed in the city of Toledo (1,970 persons) are among those whose education does not go beyond the compulsory secondary level. However, there are groups whose level of studies is such that they have not been registered as unemployed, such as those who have completed class 1 professional training, or those with virtually nonexistent unemployment rates (less than 0.1%), which is the case of unemployed with high school degrees or professional expertise.

The largest group among the unemployed is those who have no qualifications (27.27%).

Politics

Toledo has a 25-member City Council, elected by closed lists every four years. The 2011 election saw a pact made between the 11 members of the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party (PSOE) and the 2 members of the United Left, to retain the position of the PSOE's Emiliano García-Page Sánchez as mayor, which he has been since 2007.

Culture

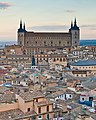

The old city is located on a mountaintop with a 150 degree view, surrounded on three sides by a bend in the Tagus River, and contains many historical sites, including the Alcázar, the cathedral (the primate church of Spain), and the Zocodover, a central market place.

From the 4th century to the 16th century about thirty synods were held at Toledo. The earliest, directed against Priscillian, assembled in 400. At the synod of 589 the Visigothic King Reccared declared his conversion from Arianism to Catholicism; the synod of 633 decreed uniformity of catholic liturgy throughout the Visigothic kingdom and took stringent measures against baptized Jews who had relapsed into their former faith. Other councils forbade circumcision, Jewish rites and observance of the Sabbath and festivals. Throughout the seventh century, Jews were flogged, executed, had their property confiscated, were subjected to ruinous taxes, forbidden to trade and, at times, dragged to the baptismal font.[119] The council of 681 assured to the archbishop of Toledo the primacy of Spain. At Guadamur, very close to Toledo, was dug in 1858 the Treasure of Guarrazar, the best example of Visigothic art in Spain.

As nearly one hundred early canons of Toledo found a place in the Decretum Gratiani, they exerted an important influence on the development of ecclesiastical law. The synod of 1565–1566 concerned itself with the execution of the decrees of the Council of Trent; and the last council held at Toledo, 1582–1583, was guided in detail by Philip II.

Toledo was famed for religious tolerance and had large communities of Muslims and Jews until they were expelled from Spain in 1492 (Jews) and 1502 (Mudejars). Today's city contains the religious monuments the Synagogue of Santa María la Blanca, the Synagogue of El Transito, Mosque of Cristo de la Luz and the church of San Sebastián dating from before the expulsion, still maintained in good condition. Among Ladino-speaking Sephardi Jews, in their various diasporas, the family name Toledano is still prevalent—indicating an ancestry traced back to this city (the name is also attested among non-Jews in various Spanish-speaking countries).

In the 13th century, Toledo was a major cultural centre under the guidance of Alfonso X, called "El Sabio" ("the Wise") for his love of learning. The Toledo School of Translators, that had commenced under Archbishop Raymond of Toledo, continued to bring vast stores of knowledge to Europe by rendering great academic and philosophical works in Arabic into Latin. The Palacio de Galiana, built in the Mudéjar style, is one of the monuments that remain from that period.

The Cathedral of Toledo (Catedral de Toledo) was built between 1226–1493 and modeled after the Bourges Cathedral, though it also combines some characteristics of the Mudéjar style. It is remarkable for its incorporation of light and features the Baroque altar called El Transparente, several stories high, with fantastic figures of stucco, paintings, bronze castings, and multiple colors of marble, a masterpiece of medieval mixed media by Narciso Tomé topped by the daily effect for just a few minutes of a shaft of light from which this feature of the cathedral derives its name. Two notable bridges secured access to Toledo across the Tajo, the Alcántara bridge and the later built San Martín bridge.

The Monasterio de San Juan de los Reyes is a Franciscan monastery, built 1477–1504, in a remarkable combination of Gothic-Spanish-Flemish style with Mudéjar ornamentation.

Toledo was home to El Greco for the latter part of his life, and is the subject of some of his most famous paintings, including The Burial of the Count of Orgaz, exhibited in the Church of Santo Tomé.

When Philip II moved the royal court from Toledo to Madrid in 1561, the old city went into a slow decline from which it never recovered.

Toledo steel

Toledo has been a traditional sword-making, steel-working centre since about 500 BC, and came to the attention of Rome when used by Hannibal in the Punic Wars. Soon, it became a standard source of weaponry for Roman Legions.[120]

Toledo steel was famed for its very high quality alloy,[121] whereas Damascene steel, a competitor from the Middle Ages on, was famed for a specific metal-working technique.[122]

Today there is a significant trade, and many shops offer all kinds of swords to their customers, whether historical or modern films swords, as well as medieval armors and from other times, which are also exported to other countries.

Gastronomy

Toledo's cuisine is grouped with that of Castile–La Mancha, well-set in its traditions and closely linked to hunting and grazing. A good number of recipes are the result of a combination of Moorish and Christian influences.

Some of its specialties include lamb roast or stew, cochifrito, alubias con perdiz (beans with partridge) and perdiz estofoda (partridge stew), carcamusa, migas, gachas manchegas, and tortilla a la magra. Two of the city's most famous food productions are Manchego cheese and marzipan, which has a Protected Geographical Indication (mazapán de Toledo).[123][124]

Holidays

- Virgen del Valle: This pilgrimage is celebrated on May 1 at the Ermita de la Virgen del Valle, with a concentration popular holiday in that place.

- Holy Week: Declared of National Tourist Interest, is held in spring with various processions, highlighting those that take place on Good Friday, and religious and cultural events. Since the Civil War, most of the steps were burned or destroyed, so it had to create new steps or using images from other churches and convents Toledo. Being a city Toledo Castile, Holy Week is characterized as austere and introspective, as well as beauty, due in part to the beautiful framework in which it takes place: Toledo. Many people take advantage of the Easter break to visit the monastery churches that are only open to the general public at this time of year. [42]

- Corpus Christi: Feast declared International Tourist Interest. Its origins lie in the thirteenth century and is probably the most beautiful Corpus Christi there. The processional cortege travels around two kilometres (1.2 miles) of streets and richly decorated awnings. In recent years, following the transfer of the traditional holiday Thursday present Sunday, was chosen to conduct two processions, one each of these days, with certain differences in members and protocol between them. [43]

- Virgen del Sagrario: On August 15 they celebrate the festival in honor of the Virgen del Sagrario. Procession is held inside the Cathedral and drinking water of the Virgin in jars.

Apart from these festivals should be noted that patterns of Toledo are:

- San Ildefonso, Toledo Visigoth bishop whose feast day is January 23.

- Santa Leocadia, virgin and martyr of Roman Hispania, which falls on December 9.

Main sights

The city of Toledo was declared a Historic-Artistic Site in 1940, UNESCO later given the title of World Heritage in 1987. Sights include:

Great sights

- The Alcázar of Toledo: Current headquarters of the Army Museum in the city. Its construction dates back to Roman times. During the reigns of Alfonso VI and Alfonso X the Wise is re-created, giving rise to the first square-shaped fortress with towers at the corners. With the emperor Charles V is rebuilt again, this time, by the architect Alonso de Covarrubias. The façades are Renaissance, with turrets and crenellated defense, raised according to the first traces of Alonso de Covarrubias and after Juan de Herrera. After the last rebuild houses offices of the Army and the Museum. It is based on granite rock on the highest promontory of Toledo, within the walls of the city, but at the same time dominating it. Thanks to its strategic location, the Alcázar represents a summary of the main episodes of their national history, as it has been the scene of both medieval adventures and witnesses of twentieth-century wars.[125]

- Monasterio de San Juan de los Reyes: It was a commission of the Catholic Monarchs in thanksgiving for the victory in the Battle of Toro. In this place the queen had the intention to be buried, although later it changed of opinion after the conquest of Granada in 1492. Juan Guas was the one in charge to carry out the works. It is a single nave with lateral chapels between the buttresses. In its main facade detach the chains of released prisoners. It has a cloister of late Gothic and the roof of the second floor is Mudéjar style. Its church has a single stellar dome nave. Also emphasizes the greater chapel decorated with shields of Catholic Monarchs supported by great eagles, conopial arches and figures of saints. The volumes are covered with a thick decoration in which has a lot to do with an outstanding group of sculptors. Vegetable, animal and human elements complete the decoration.[126]

- Cathedral of Toledo: This one contains many of the best works of art that the great majority of the museums of Europe; It also has an interesting history and a complex architecture.[127] It is a gothic building from the 13th century, erected on the old Arab mosque, that in turn was built on a previous Visigothic and Christian temple. It was promoted by Archbishop Jiménez de Rada. Its scenes carved in stone, on the life of Christ, were a true catechism during the Middle Ages. Contemplated beginning at its outer left end, we will travel from the Annunciation to the Last Judgment. The doors are a fundamental part of the main facade. In addition to the aforementioned, the Puerta del Perdón, in the center of the main facade, is 15th century, fully Gothic, and only opens on large occasions. The most modern Puerta de los Leones has one of the most important Spanish-Flemish sculptures in the 15th century, that reach their summit in the representation of the Virgin, in its mullion. Beautiful sculptures and stained-glass windows of kings, archbishops, etc., are contemplated here.

- Mosque Mezquita del Cristo de la Luz: The original building is of almost square plan of Califal period. Its state of preservation is practically intact and constitutes, by its originality, the most important exhibition of the Islamic art in Toledo. It was erected in 999 by the architect Musa ibn Ali, according to an inscription in Kufic characters on the main façade. The interiors are divided in nine spaces covered with ribbed vaults, all different, thanks to four free columns with Visigothic capitals on which twelve horseshoe arches turn. In the 12th century a Romanesque-Mudéjar head was added, formed by a semicircular apse and rectangular presbytery, and decorated interiorly with Romanesque frescoes, to adapt it to Christian worship. Outside it is decorated with blind arches of horseshoe, being the access composed of three doors with three different arches: polilobulate, of half point and of horseshoe.

- Bridge Puente de San Martín: A bridge located to the west of the city, it existed already in the middle of 14th century, replacing another one of boats located in its environs. Destroyed in the fratricidal war between Peter I and Henry II, it was rebuilt by order of the bishop Pedro Tenorio. It has five arches pointed on sturdy pillars and has two hexagonal turrets at its ends. The entrance to the city is presided over by a great imperial shield with its corresponding seated kings. The inner turret is very disfigured by later additions and reforms, under the reign of Charles II, while the exterior keeps its ribbed vaults and ogival arches and horseshoe.

- Bridge Puente de Alcántara: Of Roman origin, it was very damaged and rebuilt in the 10th century. This is when the third ring, reduced to a gate with a horseshoe arch, disappears. Under the reign of Alfonso X suffered serious damages and was reconstructed. To this last period belongs the western tower, soon modified and decorated under the reign of Catholic Monarchs, whose arms decorate its walls. The fruit of the Granada is lacking in them, since the reconquest was not yet finished. The eastern tower was replaced by a Baroque triumphal arch in 1721, given its ruinous state.

- Hospital de Santa Cruz: The architect who was best able to adapt to the new needs was Enrique Egas who, following the hospital policy of the Catholic Monarchs, designed the royal hospitals of Santiago de Compostela and Granada, and that of Santa Cruz de Toledo, founded by Cardinal Don Pedro González de Mendoza. The construction of these functional buildings corresponded to a modern state policy of assistance to the sick and marginal sectors of society, aimed at preventing begging, coinciding with the new ideas of cleanliness, adornment and decorum of the Renaissance city. The model established for this purpose, first tried in Santiago de Compostela in 1501, seems inspired by the cruciform arrangement of the Ospedale Maggiore of Milan, built by Filarete (1456-1465) -a square plan with two cross-shaped cross-sections in the form of a Greek cross, they originate four courtyards of regular proportions. Although its smaller proportions with respect to the reference model approaches it more to other solutions, also Italian, like Hospital of Santo Spiritu de Sassia, constructed in Rome between 1474 and 1482. Independently of the novel character of the model, later developed in Toledo, In Granada and in the New World, the structural, technical and ornamental solutions with which all these examples materialized belong to Gothic architecture. Alonso de Covarrubias would be the author of the sculptural parts and who designed the stairway that accesses from the cloister to the upper parts of the building, which is accessed by a triple archway-middle point the central, escarzanos the lateral - that reminds the Arches of triumph.[128]

- Hospital de Tavera: The "first totally classical building of Castile", also known as Hospital Tavera or Outside, being located outside the city, in front of the Puerta de Bisagra, was built in the 16th century with a double function: hospital for " Different diseases "and pantheon of its founder, Cardinal Juan Pardo Tavera. Its construction opens in 1540 the program of architectural and urban renewal that the circle of humanists who surrounded the Emperor Charles V designed to adapt the image of Toledo to his role as Imperial Capital. Its interior houses a great gallery, with works by the great masters of the 16th and 17th centuries: El Greco, Zurbarán, Tintoretto. In addition to a large collection of Flemish furniture and tapestries of the Golden Age.[129]

- Iglesia de Santo Tomé: The most visited parish church in the whole city, thanks to the painting of El Greco "Burial of the Lord of Orgaz", one of the masterpieces of painting of all time, installed on the tomb of the same. The church, of early foundation after the taking of the city by Alfonso VI, occupied a mosque, being completely rebuilt in the 16th century precisely by the Lord of Orgaz, Don Gonzalo Ruiz de Toledo. Almost nothing remains of that reform, erased by those who succeeded in each new era of changing artistic tastes. It is of three naves with cruise, covered by barrel vaults during the Renaissance and polygonal apse. Its Mudéjar tower is very similar to the one of the church of San Román, of square plant with two levels of spans framed by double arches, separated by a row of separated blind arches - unique in the city - by columns of ceramics of Talavera de la Reina.

- Taller del Moro: The Museum Taller del Moro in Toledo is housed in an old Mudéjar palace from the 14th century, and houses samples of Mudéjar art and crafts from the 14th and 15th centuries. Its name is due to that, according to the tradition, this place served during the Average Age of warehouse and repair shop of the materials for the factory of the Cathedral. The centerpiece is dedicated to the collection of Toledan Mudéjar ceramic and tile in the 14th and 15th centuries. In the room on the right are exhibited samples of wood crafts, especially that used in the old houses, such as beams, friezes, canecillos and carved tablets. Finally, the left alcove is dedicated to the archaeological remains and it keeps tombstones, cipos, Córdoban capitals and boats of the time. The museum was built in 1963 when the state acquired and restored the building. In Mudéjar style, its disposition is Muslim so it remembers to the stays of the Alhambra. The conserved consists of a central hall and two lateral rooms communicated to each other by arches of rich plasterwork and covered by wooden roofs. Surrounding the building is a gallery with a roof on the main floor, on columns of Ionian capital stone. It has two Renaissance facades that give access to the building; Are made of stone, brick and masonry.

Gates and walls

- Gate Puerta de Bisagra: It is of Muslim origin, of whose time it conserves rest in the second interior body. Its name derives from the Arabic word Bab-Shagra, that means "Door of the Sagra". It was completely rebuilt under the reigns of Charles V and Philip II, according to the traces of Alonso de Covarrubias. It is formed by two bodies, among which a square of arms is inserted. The monumental outer body is formed by a triumphal arch of cushioned sillares, crowned by an enormous imperial shield of the city, with its unmistakable two-headed eagle and flanked by two large semicircular masonry towers with the figures of two sedentary kings, symbol of the good Government of the medieval shield. The interior body is of a half-point arch flanked by square turrets crowned by ceramic spiers, in one of whose faces appears the imperial shield of Charles V, and checkered in others. The monumental and non-defensive character is evident in the inversion of the embrasures located almost at the ground floor and sillares in relief crowning the towers.

- Gate Puerta de Alarcones: It is an Albarrana tower that conformed, next to the gate Puerta del Sol, the best defended access of the Islamic time. The gate, lacking in ornamentation, retains a very refurbished ashlar factory in the lower part and in the arch, changing its horseshoe shape in half a point. Its upper body was disfigured in the 17th century, when it is allowed to reform it in dependencies of a nearby convent.

- Gate Puerta de Alcántara: It is one of the most important gates of the military precinct, on the eastern wall. It is of Arab origin, as it reveals its elbow structure, although it was rebuilt in Christian times. The gateway is a horseshoe arch and is flanked by two square towers with lateral loopholes. Its structure has been preserved to this day by being blinded from the 16th century until the year 1911. The space between this gates and the bridge formed a square closed by two other side gates.

- Gate Puerta de Bab-al-Mardum: The gate of Bab-al-Mardum was one of those that allowed the access to the Islamic Toledan medina. Its Muslim name indicates that during a certain time it was closed, being used like main passage the near gate Puerta del Sol, more accessible and with less slope. Its oldest remains are dated around the 9th and 10th centuries, although the first documents that mention it are of later date. The loss of its defensive value meant the disappearance of the upper room and its primitive towers possibly already in the 15th century. At that time it was known as the gate of the Butler or gate of the Cross and in it lived the corregidor of the city. It was also prison and had other duties. The Catholic Monarchs ceded it to Pedro Lasso de Castilla. In the power of his descendants, the Mendoza, was well into the 18th century. Later it was used by the Hospital de San Lázaro to take care of the patients of ringworm, leprosy and scabies. Since the end of the 19th century it has been used as a private dwelling. The access through these gates had to be made by two horseshoe arches, which were later modified to convert them into semicircular arches, on which is located the upper body that served as a room, distinguished externally with the typical Toledan rig. Some blind holes, and a window, account for changes in its use.

- Gate Puerta de Alfonso VI: To distinguish it from the gate Puerta Nueva de Bisabra, it was also called Alfonso VI. It conserves, to a large extent, its primitive structure, the only one of straight entrance, reformed in 13th century in layered, guarded by strong towers advanced of style essentially Califal. In its exterior facade shows a curious horseshoe arch surrounded by alfiz, crossed by a lintel and crowned in the key with a Visigothic relief. The three arches and the windows of the upper part are the result of the aforementioned Mudéjar reform that introduces masonry and brick on ashlars and an interior rake to prevent the passage to the enemy.

- Gate Puerta de Doce Cantos: It is the most modest of all the gates and the only one that no longer fulfills its function of giving passage from the neighborhood of Alficén to the bridge Puente de Alcántara. It did not drive outside the city, but to the fortified square Plaza de Armas the gate Puerta de Alcántara. It was blinded for long centuries and with the urban reforms in the 20s of the 20th century but its Arab structure was altered.

- Gate Puerta del Cambrón: Gate of Muslim origin, very modified. In its current version dates back to 1576, and was structured in square plan based on a small inner courtyard surrounded by four towers covered by slate spiers. On both sides there are Renaissance doorways with coat of arms, the one of the city to the outside and the one of Philip II to the interior. Beneath this is a beautiful image of Saint Leocadia, patroness of Toledo and this door that is the only one open to traffic. Its name comes from the cambroneras, thorny bushes that grew in the place.

- Gate Puerta del Sol: Albarrana tower that was probably built in the times of the Taifa kingdom, as indicated by its inner horseshoe arches. It was rebuilt in the 14th century in Mudéjar style, with the use of typical materials: sillares, masonry and brick. The vain is a horseshoe arch framed in another on which appears a double frieze of archery, on the arch, in the 16th century, was added a relief with the emblem of the Cathedral under the moon and the sun (that gives name to the door). The matacanes, the buffards and the battlements give him military aspect, although his function would already be more of triumphal arch than defensive. It contains some elements unlike its style, like the remains of a Paleocristian sarcophagus or a small classic bust.

Baths and caves

- Baths Baños de Tenerías: The Islamic Baths of Tenerías are a set of structures related to the water, belonging to the Muslim world, and realized with brick factory and compartmentalized in several rooms or rooms whose decks have disappeared. These are accessed through a door made in a fence that closes the entire site. The whole is surrounded by a path that borders and allows contemplation from a close perspective. In addition, a raised platform and an explanatory panel help to understand the globality of the deposit.

- Baths Baños del Caballel: Date from the year 1183 and are located in an area full of baths and laundries that confirm the importance that the Muslim settlers gave to these services.

- Baths Baños del Ángel: It is one of the best preserved of the eight that still maintain structures recognizable within the Historic Centre of Toledo. The restored room corresponds to the hot and, unlike other bathrooms, maintains the hypocaust or glory with much of the pillars that supported the floor of the room. Some of them were plundered and those that are preserved present the deterioration typical of the flames with which the room was heated. Although at the moment the only two accesses from the street to the bathroom are in the street of the Ángel, originally had to be in the street of Santa María La Blanca, which would suppose a great proximity to the synagogue of the same name.

- Baths Baños del Cenizal: The refurbishment works in the Islamic baths of del Cenizal, preserved in the cellars under the building of the street Bajada del Colegio de Infantes nº 14, have had as purpose its conversion into a visitable space, by means of its putting in value with an appropriate approach of recovery of its most remarkable elements. The intervention carried out by the Consortium of Toledo has focused on two of the rooms that make up the bath or hammam: the entrance hall and the cold room, since the rest of the rooms (warm room and temperate room) are conserved under the surrounding buildings.

- Baths Baños de Hércules: The site that houses the so-called Caves of Hércules (alley of San Ginés, 3) has a rich architectural history, as it has been occupied by different buildings throughout history: in Roman times a water tank had been built here to supplying the city, which was part of the Roman Toletum hydraulic network. Later, already in Visigothic time, it seems that on the deposit of water a Christian temple was raised. Later, probably in the 12th century, a new temple was built in the same place, dedicated to San Ginés, seat of the homonymous parish. The small church of San Ginés was abandoned in the 18th century and was demolished in the 19th century (1841), leaving only some of its perimeter walls, part of the sacristy and basements.

- Basements and Well Sótanos y Pozo de El Salvador: The square of El Salvador is associated with the convent building of San Marcos, now converted into a cultural center and municipal archive. Originally, the building extended by the current square, developing its cloister by this space. In 1997, there were archaeological tastings in the same square and it was possible to verify the existence of a vaulted basement that was partially filled with debris. Subsequently, the manual archaeological excavation carried out by the Toledo Consortium in 2002 discovered a large vaulted basement that runs parallel to Trinidad Street and extends through a door in the direction of the square itself.

- Casa del Judío: The Casa del Judío means "House of the Jew" is located in the heart of the Jewish quarter of Toledo. The two spaces that generate interest in the interior of the building are the courtyard, which preserves a multitude of plasterwork and, above all, the basement, possibly a Jewish liturgical bath or miqva, whose function was spiritual purification and preparation for some An important event in the life of a Jew. During its restoration these have been discovered in adjacent hidraulic sites to the almagra and a cistern that help to support the theory on its use.

Roman remains

- Roman circus: The ruins of the Roman circus are located in the Vega Baja, on both sides of the avenue of Carlos III, which disappeared a good part of the base of its stand. Its orientation from northeast to southwest avoided the dazzle of the participants. It was built at the end of the 1st century, with an elongated plant, 408 meters, consisting of two straight and parallel sides, 86.2 meters apart, and two other curves. From the western end, semicircular and supported in twenty-two vaults began the careers of chariots. A small wall, the spina, separated the two directions. The existing vaults supported several levels of stands that could hold up to 13,000 spectators. From the large access doors only emerge its upper parts at both ends. It worked until the 4th century. Its subsequent abandonment caused the disappearance of the noble materials of its lining. It had uses like cemetery in different times, location of potters and it served of shelter to vagabonds at the end of 18th century, reason why Cardinal Lorenzana had to throw several vaults that still were maintained. Currently much of it is integrated in the park known as Campo Escolar created in 1906 to celebrate the Fiesta del Árbol, recovering that empty terrain outside the walls as the urbanization of the neighborhood would take almost half a century. In its immediate vicinity was the Roman theater, on the site occupied today by a college.